121 years after Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’, his great-grandnephew has resurrected the vampire... and his creator

A previously unseen preface to the original 1897 novel and a journal hidden since that time: Dacre Stoker tells David Barnett how his new novel took an unexpected turn

On Halloween night when Dacre Stoker was a boy growing up in Montreal, trick-or-treaters would knock on the door of the family home and ask, “Are you going to give us candy, or are you going to give us blood?”

At least, the ones of a more literary bent would, those who had made the connection between the family surname and that of the author of the all-time classic horror story, Dracula.

But it wasn’t until Dacre was about 12 and asked his father about it that he realised that not only did he share a name with Bram Stoker, he was actually related to the Irish writer – he was his great-grandnephew.

He read Dracula at 12, but it wasn’t until he was at university that he properly applied himself to reading it more in-depth, saying, “I read it in an original edition, signed by Bram”.

But the discovery of his link to arguably the most famous horror writer in history didn’t turn the young Dacre into some kind of tortured, gothic figure – far from it.

“My life when I was younger was dominated by sports,” he says. “I really didn’t have the time or interest in Dracula or my ancestor.”

Dacre isn’t joking: he was a member of the Canadian men’s pentathlete squad and coached the team at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul. He’s also a tennis coach.

But at some point, Dacre – who’s now 60 and lives in South Carolina – became fascinated with the brother of his great-grandfather George Stoker, so much so that he’s just co-authored his second book adding to Bram’s canon, a prequel to the most famous book about vampirism ever.

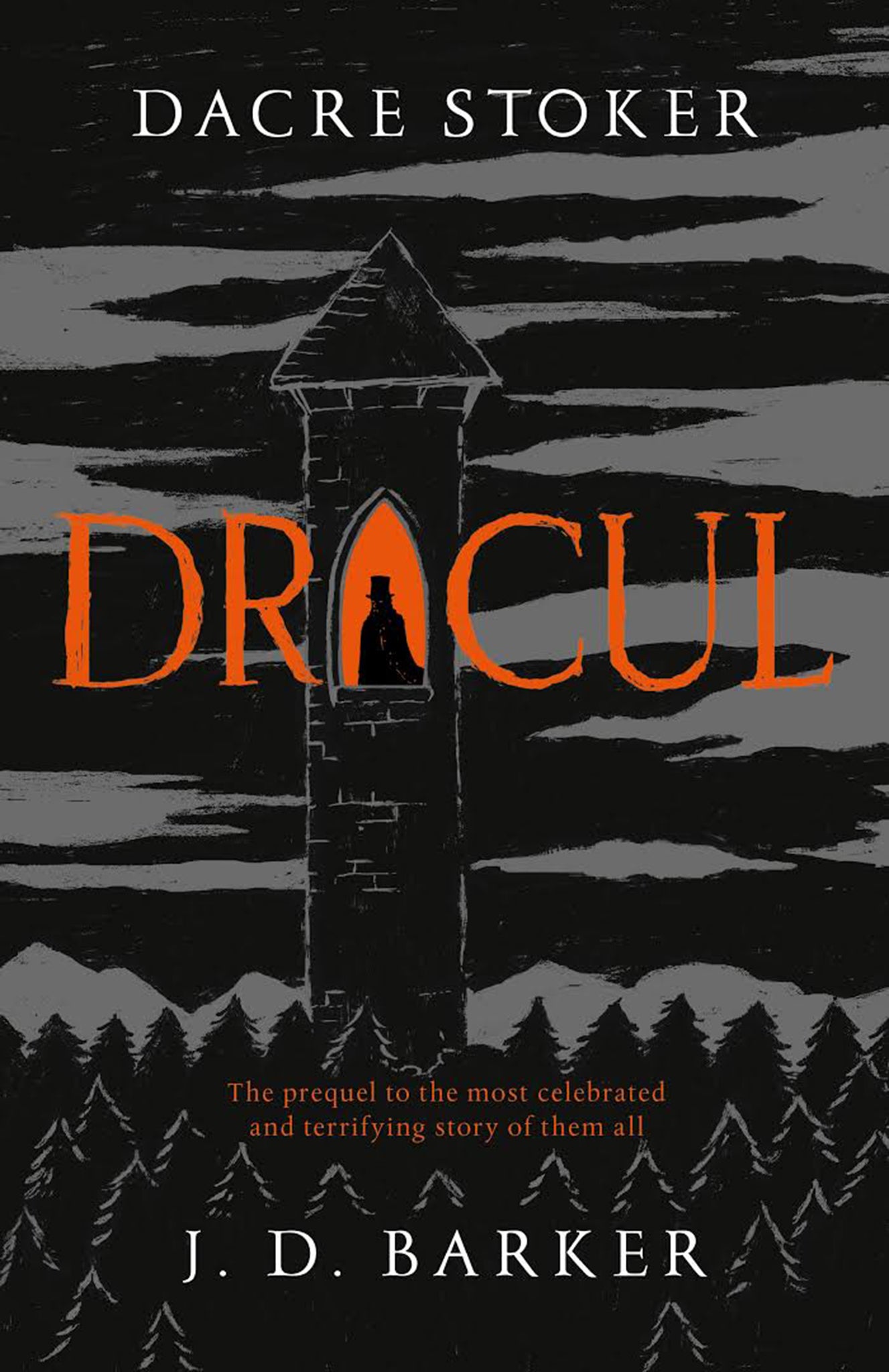

But Dracul, published this month by Bantam Press, is not just about the early life of Count Dracula himself. It ties Bram Stoker inextricably into the Dracula legend and posits the fascinating question… what if Bram was producing not just a mere entertainment, but writing from experience?

Cowriting with horror author JD Barker, Dacre presents Dracul partly in epistolary form, as the original book is laid out, intermingling the story of a terrified 21-year-old Bram locking himself away from a nightmare that haunts him, his only defences a gun, holy water and a crucifix, with fictionalised entries from Bram’s journal.

The journal tells the story of Bram as a sickly child in Dublin, who is put in the care of a sinister nanny and ultimately crosses paths with the children of the night, experiences which would later inform his 1897 novel that has, in real life, become one of the most enduring stories of the past century.

It’s great fun, told with aplomb by the two authors, and is weighted with an often uneasy sense of credibility, despite the subject matter, which is all thanks to Dacre’s direct connection to Bram, and the meticulous research he’s carried out into his ancestor’s writings.

“Bram became quite a sportsman later in life,” says Dacre. “He was a very sickly child. Imagine if this transformation was due to an infusion of vampire’s blood…”

Dacre is currently on a tour of the US promoting Dracul, and when we speak he is in New Orleans, itself considered the haunt of vampires and the quiet undead. It is very early in the day for him, before 7am, but he assures me he is an early riser. Across the road from his hotel is, he tells me, the Lafayette Cemetery, lair of the Mayfair vampires and deadly Lestat in Anne Rice’s celebrated novels. Dacre has become quite the expert on the undead. So how did the sports-mad teen gravitate towards less earthly pursuits?

“I think it was when I read In Search of Dracula, a book by two Boston scholars, that I first really felt a connection to Bram and the story of Dracula,” he says. The book, by Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally, was published in 1972 and first made the connections between the fictional Count Dracula and the very real and bloody historical figure of Vlad Tepes of Wallachia.

His interest piqued, Dacre began to speak to his cousins and other surviving relatives. “There aren’t many of us,” he says. “Although Bram was one of seven children, not many of them had families of their own.” He pauses. “Fortunately, George, my great-grandfather, did.”

In 2003, Dacre was contacted by a screenwriter called Ian Holt, who had been trying to get a film made of a direct sequel to Dracula, but without much success. The pair teamed up and wrote the story as a novel, Dracula the Un-Dead, set 25 years after the original novel. As well as having the sway of an actual Stoker family member involved, the book served to help bring Dracula back into Stoker hands; since the 1890 novel the character had become a bit of a pop-cultural free-for-all, and prompted the family to set up the Bram Stoker Estate, which Dacre manages.

But the story took an unexpected turn in 2011 when Noel Dobbs, Bram’s great-grandson, discovered hidden away in his home on the Isle of Wight a previously unseen journal kept by the great writer.

“That was a pivotal moment for me,” says Dacre. “With Dr Elizabeth Miller I set about deciphering the handwritten entries and from that journal I got to know Bram a lot more intimately. That was probably the most significant point in my relationship with Bram.”

Dacre and Dr Miller published the contents of the journal in 2012, and as well as offering an insight into the life and thoughts of the author, it also set Dacre on another journey that would lead to the writing of the new book, Dracul.

The journal alerted Dacre to the existence of a preface written by Bram to the original edition of Dracula that was never used by his publishers… and one which suggested that the author might have actually believed in vampires.

Dacre – becoming, as he says, a “forensic literary detective” – tracked down the original preface to an Icelandic translation of Dracula and eventually finding a copy of that, something became startlingly apparent. “I believe that Bram realised that many people in history truly believed that vampires were real,” he says. “After Dracula was published, he gave just one interview and in that he said his book ‘touches on mystery and fact’.

“We know now that long ago people might not have understood things like the plague or communicable diseases, and these unexplained things might have seemed supernatural to them. I believe Bram was very open-minded, and believed that just because we can’t observe something, it doesn’t mean that it can’t exist.”

Dacre quotes from the original Dracula to me, from the scene when Van Helsing is trying to convince Dr Seward that there are things out there beyond human ken. “There are mysteries which men can only guess at, which age by age they may solve only in part. Believe me, we are now on the verge of one.”

From all this, Dacre extrapolated the plot of Dracul, of a young Bram coming into contact with vampirism, and writing Dracula as a result. “Not as a piece of fiction,” says Dacre, “but as a warning to the world.”

When the idea was germinating, Dacre met JD Barker, whose debut novel Forsaken was nominated for the Bram Stoker Award for horror fiction. They agreed to collaborate on the idea, with Dacre taking Barker up to his cabin in North Carolina to thrash out the plot. The wisdom of accepting an offer from Bram Stoker’s blood relative to spend time alone in a remote cabin briefly flits across my mind as something to be embarked upon with care, but I don’t voice it, instead asking Dacre what Bram would think of the result.

“I really do think he would approve,” he says. “I wanted to show the character of Bram evolve into a hero. He never really liked talking about himself and I think he would like the idea of a relative of his telling the story of his humble beginnings.”

As well as managing the Stoker Estate and writing his own books based on Bram’s work, Dacre spends a lot of time attending scholarly conferences and is a regular attendee at the goth weekend in Whitby, where Bram holidayed in 1890 and first got the idea for Dracula. In the book, it is where the vampiric count makes landfall on the ill-fated ship the Demeter. The image of the Demeter crashing into the beach after Dracula has helped himself to most of the crew was based on a true story Bram was told by the fishermen on the harbour, about the Dmitry which beached at Whitby in 1885.

If Bram Stoker kept an open mind about the real existence of vampires, what about his great grandnephew? “I keep an open mind about a lot of things, too,” he says. What would he do if he met an actual vampire?

“I did!” he declares. “Last night! And not just one. There are now people who practise what they call ‘safe vampirism’. They share blood. I was invited to go along to one of their private clubs last night…”

Quite what Bram Stoker would have made of that, we can only guess. But my interview with Dacre is at an end. The sun is just beginning to rise, and I wouldn’t want to keep him any longer. Because you just never know for sure…

‘Dracul’ by Dacre Stoker and JD Barker is published on 18 October by Bantam Press, £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments