Diane Abbott’s treatment on ‘Question Time’ proves media and politics are entrenched in bias

Repeat interruptions, short introductions and a minimisation of the shadow home secretary on the BBC programme indicate implicit bias, say Robin Bunce and Paul Field

Question Time has put issues of media bias back in the headlines. For Diane Abbott, a politician with extensive media experience, the show was a “horrible experience”, the worst of her many appearances on the programme. Having appeared on something like 30 episodes, that’s significant. After all, some of her early experiences were almost as eventful.

Her appearance on Question Time in July 1987 was particularly memorable. Abbott shared a panel with Liberal MP Cyril Smith and Conservative minister Michael Heseltine, with Robin Day in the chair. Then, as now, it was the discussion of opinion polls that caused uproar. The polls, Smith commented forcefully, showed that Labour was unelectable, “and one of the reasons for it,” he added, “is Diane Abbott and people like her...”

The largely white audience applauded, and after a moment’s delay chuckled, seeming to get some unspoken joke. Abbott called him out: “If Mr Smith believes that having black people in parliament for the first time is in some sense a backward step, thousands of people that voted for me in Hackney North would disagree.”

The response was immediate. For Heseltine this was beyond the pale. He appealed to Day to intervene. The audience protested vocally. “I honestly believe,” said one white man, “that the vast majority of the audience here do not see Diane as a black person.” This went down well, as did his thought that Abbott was the panellist showing true prejudice for assuming that white people perceived race. Day wrapped up the discussion apologising to the audience for calling Abbott black, his implication being that unless he had said so, none of the white people in the crowd would have been able to tell.

The 1987 episode exposes the nature of the assumptions of many white Britons about race in Thatcher’s Britain. Britain was, as Heseltine put it, a harmonious and tolerant country, white people were effectively “colourblind”, and black people who claimed otherwise were either deluded or harbouring their own anti-white prejudice.

In the same way, Question Time says something important about the nature of our politics, its entrenched biases, and which political figures are taken seriously.

Evidence of bias on the show is best illustrated through comparison. Abbott was interrupted twice as often as prisons minister Rory Stewart, even though Stewart spoke more often, and for more of the show. The introductions at the top of the show were far from even-handed. Stewart’s introduction covered his ministerial career, past and present, as well as his governorships in Iraq.

For all her achievements, for all of her experience, Abbott was not treated with the same degree of respect as Stewart or Oakeshott, her voice was not given as much weight

By comparison, Abbott’s introduction was short on detail. What is more, by linking her position as shadow home secretary to her relationship with Jeremy Corbyn, there was an implication that Abbott owed her job to a personal relationship, rather than merit. Indeed, according to several audience members, this was precisely the point made by Fiona Bruce before the show. Equally, in introducing Abbott, Bruce failed to mention her time as shadow minister for public health, her years on the Foreign Affairs Select Committee or the Treasury Select Committee, nor did she mention that Abbott is the first black woman to be elected to the Commons.

Then there was Bruce’s decision to side with journalist Isabel Oakeshott’s wholly inaccurate statement that Labour was “way behind... miles behind” in the polls. At the same time, she was quick to assure the audience that Abbott was “definitely” wrong in her contention that the two main parties were essentially “level pegging”. In reality, as the BBC has subsequently acknowledged, Abbott was correct.

Although this was never said explicitly, the constant interruptions (21 times compared to nine interruptions of Stewart and eight of the SNP’s Kirsty Blackman), the minimisation of Abbott’s achievements, the willingness to “correct” Abbott when she was in the right, all indicate that in some important sense, Abbott was out of place. For all her achievements, for all of her experience, Abbott was not treated with the same degree of respect as Stewart or Oakeshott, her voice was not given as much weight: in short, she was not treated as a serious political figure.

Why not? Abbott’s treatment is perplexing. In some ways, her biography is similar to many of our political leaders. Educated at an elite university, she went on to have a career in Whitehall, then the media, and then parliament. But the fact that Abbott is a black woman, from a working-class family gives each stage of this story a different significance.

She won her place at Cambridge in 1973, at a time when only 10 per cent of the university’s students were women. While the university did not collect data on student ethnicity at the time, recent research shows that she was the second black person to study at Newnham in its century-long history, and only the third black person to study history at Cambridge in the 750 years since the university’s foundation.

For politicians such as Jacob Rees-Mogg and Boris Johnson, success in university politics was part of their path to Westminster. Not so for Abbott, who had little time for college debating societies. Her antipathy to university politics is easy to explain. Enoch Powell was honorary president of the university’s Conservative Society when Abbott started at Cambridge, and women were excluded from many of Cambridge’s student societies. But more than that, Abbott found the concerns of student politics essentially elitist.

Abbott’s path from university to parliament was anything but straightforward. She entered the Commons in 1987, at a time when there were no black people in the house, at a time when fewer than 5 per cent of MPs were women, and at a time when there was widespread suspicion of black radicalism. Abbott’s historic success was the result of a decade of activism, working with black organisations, and within the Labour Party.

In 1978 Abbott became involved with the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), an umbrella organisation for black and Asian women’s groups. Founded by radicals including Stella Dadzie and Olive Morris, Abbott believed that the black womanism she encountered at OWAAD was far more sophisticated and rooted in the concerns of working-class black women than the student politics she had experienced at Cambridge.

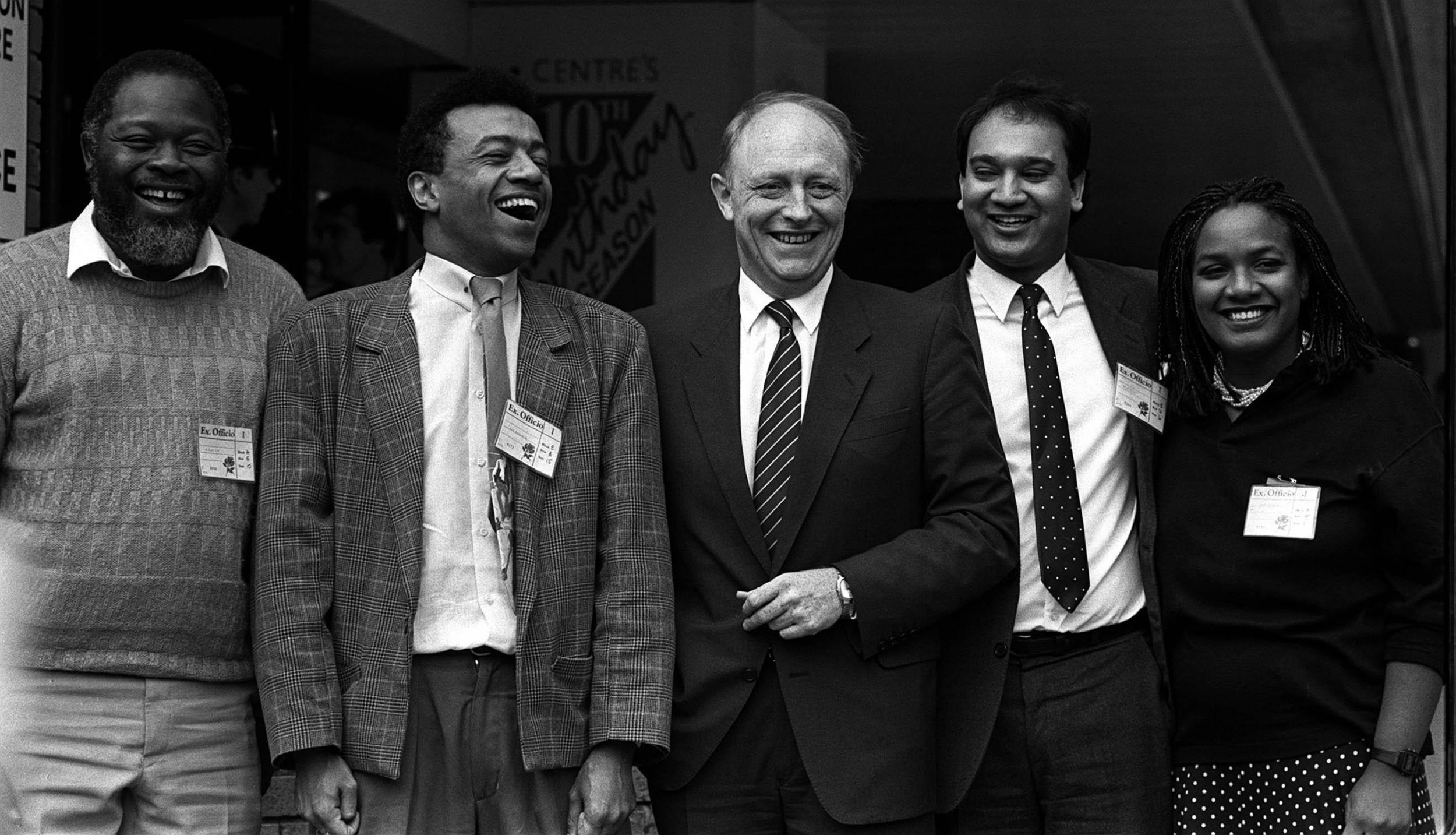

In 1983 Labour politics and black radicalism came together. Together with Russell Proffit, Elaine Foster, Marc Wadsworth and others, Abbott founded the Labour Party Black Sections movement, which fought for black representation at all levels of the party, with a view to gaining black representation at all levels of government. Black Sections was extraordinarily controversial. The right-wing press dubbed Abbott, Paul Boateng, Linda Bellos, Bernie Grant, Sharon Atkin and other LPBS activists “Black Extremists”, “Black Militants” and “Loony Left”.

In 1997, Abbott led the first backbench rebellion against Tony Blair’s cuts to lone parent benefits. She was credited at the time for being the first MP to damage the new prime minister

The movement was no less controversial inside the Labour Party, and in the run-up to the 1987 election, black candidates were regularly deselected – the party leadership seemed to feel that white voters would not turn out for black candidates. In spite of this apparent hostility from the party leadership, in spite of constant attacks in the media, four Black Sections candidates won seats in the 1987 election, Abbott (the only woman) among them.

Since 1987, Abbott has had a distinguished parliamentary career. Her first major campaign as an MP was against the imprisoning of refugees on Britain’s first private jail, the Earl William, a recently privatised and hastily repurposed car ferry. Abbott visited the Tamil refugees, many of whom had fled torture, highlighting their squalid conditions, and the absence of medical care. The Thatcher government refused to back down, even when the floating prison, nicknamed “the hulk” due to its obvious disrepair, broke its moorings and ran aground in the great storm of October 1987.

In 1997, Abbott led the first backbench rebellion against Tony Blair’s cuts to lone parent benefits. She was credited at the time for being the first MP to damage the new prime minister. Abbott also played an important role in exposing evidence of government complicity in the “arms to Africa” scandal. Someone at the top of government was clearly irked by Abbott’s efforts on the Foreign Affair Select Committee, for a government dossier on Abbott was leaked, containing material stolen from her a decade earlier.

Abbott’s skill as a parliamentarian was not lost on The Spectator. The venerable right-wing journal awarded her parliamentary speech of the year in 2008, for her forensic critique of Gordon Brown’s proposed anti-terror laws. Abbott stood for the leadership of the Labour Party in 2010, and since joining the shadow cabinet she led Labour’s attack on the government over last year’s Windrush scandal.

The first thing my staff have to do in the morning is go online and delete and block all the stuff

In spite of this long, pioneering and successful career, in spite of all of her experience in parliament, and working with grassroots campaigns, Abbott was treated with derision on Question Time.

Anti-politics, and a generalised distrust of politicians is part of the current zeitgeist. Yet, even in an age of distrust some politicians are derided more than others. Privilege insulates some individuals and groups at the expense of others. So, Oakeshott can get polling data wrong and still be taken seriously. Stewart can pull figures out of the air, and still expect to be treated with respect. But as a black woman, Abbott is routinely ridiculed, and her infrequent gaffs are seized upon as “proof” that she has no right to be at the centre of British politics.

Boris Johnson is, perhaps the best example of a British politician insulated by privilege. As an exceptionally wealthy, white man he can get away with accusing the Turkish president of having sex with a goat; he can brush off criticism following his use of the word “piccaninnies”; he was even able to accuse Barack Obama of “ancestral dislike” of Britain, and still be given the job of foreign secretary – one of the highest offices of state.

None of this is without personal consequences for Abbott, who experiences more racism now than at any time in her 35 years in politics. “Twitter has put racists into overdrive,” Abbott remarked in response to research published by Amnesty International in December 2018. The research showed that black women in journalism and politics were 84 per cent more likely than white women to be mentioned in abusive tweets. “The first thing my staff have to do in the morning is go online and delete and block all the stuff,” she said.

An earlier study by Amnesty of 900,223 tweets sent in the six months before the 2017 election revealed that Abbott received 45 per cent of all abusive tweets sent to women MPs, 10 times more than other women in parliament. According to Abbott: “It’s highly racialised and it’s also gendered because people talk about rape and they talk about my physical appearance in a way they wouldn’t talk about a man. I’m abused as a female politician and I’m abused as a black politician.”

During the 2016 US election, Trump claimed infamously that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue without losing any voters. He was so insulated by his status that “his people” would still support him, even if he was guilty of murder. Sadly, as Question Time shows, a similar relationship between privilege and bias is at work in British politics.

Robin Bunce is a historian based at Homerton College, University of Cambridge; Paul Field is a lawyer, writer and human rights activist

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments