The language of diabetes harms sufferers – it’s time for change

People living with diabetes can be left bewildered by a blame narrative encouraged by the media, and even by the medical profession, says James Moore

Diabetes eh. It’s a plague, I tell you, a plague. It’s an epidemic caused by bad lifestyle choices. It’s going to break the NHS.

It goes hand in hand with obesity. That’s also a plague, another epidemic caused by bad lifestyle choices that’s going to break the NHS.

These notions encapsulate the ugly narrative that has been allowed to develop in the media about a condition that affects 3.7m Britons, aided and abetted by an awful lot of people who really ought to know better. You’ll see variations on the theme peddled by the BBC, newspapers, and by many other outlets.

It makes life extremely tough for everyone who is dealing with a condition that imposes significant challenges, a condition that isn’t as simple as people have been led to believe.

There is more than one type of diabetes. The one which prompts most of the negative coverage is Type 2. Some of the people who live with it take a lot of unjustified flak.

So do those of us suffering from Type 1, the causes of which are quite different. Ditto some of the symptoms and the treatment regime.

It has been argued that the categorisations ought to be renamed to better reflect what these conditions really are, how they function, and, as a corollary, to better educate the public about them. The current situation serves neither type particularly well.

For the record, Type 1 is thought to be an autoimmune disorder (although that hasn’t been established beyond all reasonable doubt). It usually strikes when people are young, most commonly when they are adolescents. But some get it earlier – I was diagnosed at the age of two – and some aren’t affected by it until later in life. The prime minister, Theresa May, is in the latter group.

You get it through the body’s immune system knocking out the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, which in turn prevents it from metabolising carbohydrate that, left untreated, builds up in the blood, leading to a long list of life-threatening complications.

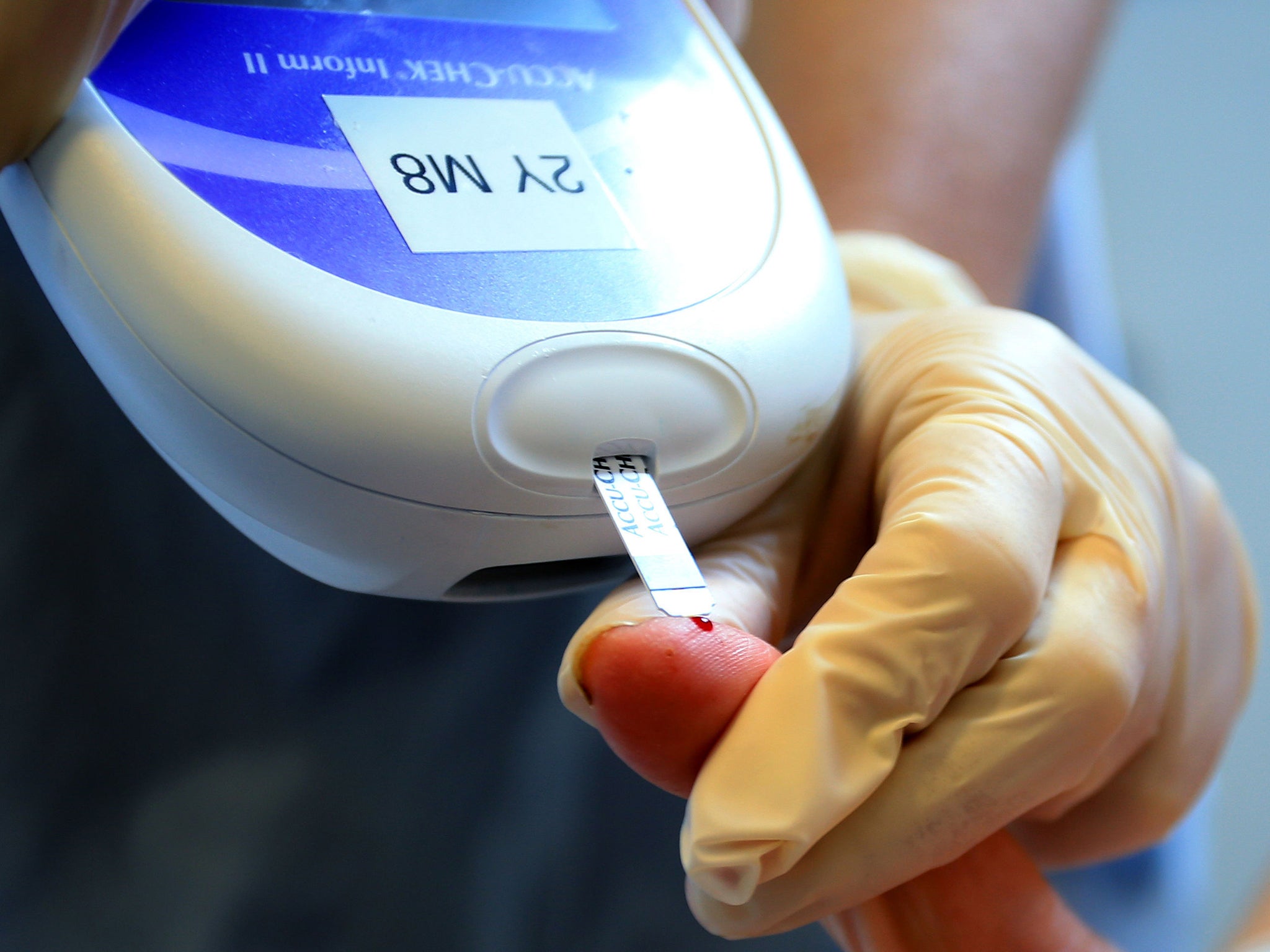

It’s fatal if proper treatment isn’t forthcoming; and there is no cure. People like me simply have to get used to life as human pin cushions, injecting insulin several times a day and monitoring our blood sugar regularly via pin prick tests (although alternatives such as insulin pumps and electrode based testing are now increasingly in use).

About one in ten of the people known collectively as “diabetics” are Type 1s.

Type 2 usually strikes later in life, as a result of the body becoming resistant to the insulin it produces. Because the hormone doesn’t work properly, blood glucose levels rise, and more insulin is released. Sometimes the pancreas wears out as a result of the process, making less and less insulin, causing higher and higher blood glucose levels.

The end result can be that a Type 2 sufferer ends up requiring a similar sort of regime to the one Type 1s are on. But some people, like deputy Labour leader, Tom Watson, can better manage the problem through adopting a healthier diet, losing weight, and becoming more active.

A name change is not a monumental task. It has been done before. The time has come to do it again

Let’s face it, most of us would benefit from that.

The majority of Type 2s eventually need some form of medication – either drugs, or sometimes insulin injections – and regular blood tests as well.

Age is obviously a risk factor, and so is obesity. But before people start talking about lifestyle choices and berating Type 2s, it should be noted that their genes play an important role (as is the case with Type 1, although the two conditions have largely distinct genetic bases). So does their ethnicity. People with a South Asian background, for example, are particularly at risk.

The toxicity of the narrative surrounding the condition(s) is perhaps hardest on young people diagnosed with Type 1.

They often find themselves running a gauntlet of prejudice from the diabetes police at a time when they have it hard enough dealing with both adolescence and a chronic medical condition.

It’s a sad fact that there are people out there who seem to think it’s their right to take those with the condition to task for daring to indulge in a biscuit. Or a chocolate bar. Or (heaven forbid) a burger.

A healthy diet is a damn good idea for people with Type 1s, but by contrast to Type 2 cases like Watson’s, it isn’t going solve the problem.

Type 1s are also prone to low blood sugars, not having enough carbs available. It’s hard to describe what this feels like. I sometimes liken it to being drunk, just without the pleasant effects of alcohol – but that doesn’t quite do the sensation justice. Suffice to say, it isn’t a lot of fun.

Everyone with the condition has their own favoured way of getting sugar into their systems to deal with it. And preachy medical people often tell us why some of those methods are “wrong”. Dealing with judgemental people is another unwelcome side effect of the condition.

But if you see a diabetic scarfing down cookies, there will be a good reason for it.

Could changing the name to something like Autoimmune Diabetes help address the confusion?

Owen Headley is 16, physically active, fit, and the picture of health. He’s about as far from “Dia-Betty” – the cruel caricature featured in The Simpsons – as it’s possible to get.

Headley is among those who favour the idea. He says: “I was 11 when I was diagnosed and I didn’t know anything about diabetes. It was quite a shock. People seem to think it’s all about diet, you know, that you ate too many sweets. They’re usually alright when you explain it but it does get really tiresome having to do that all the time.”

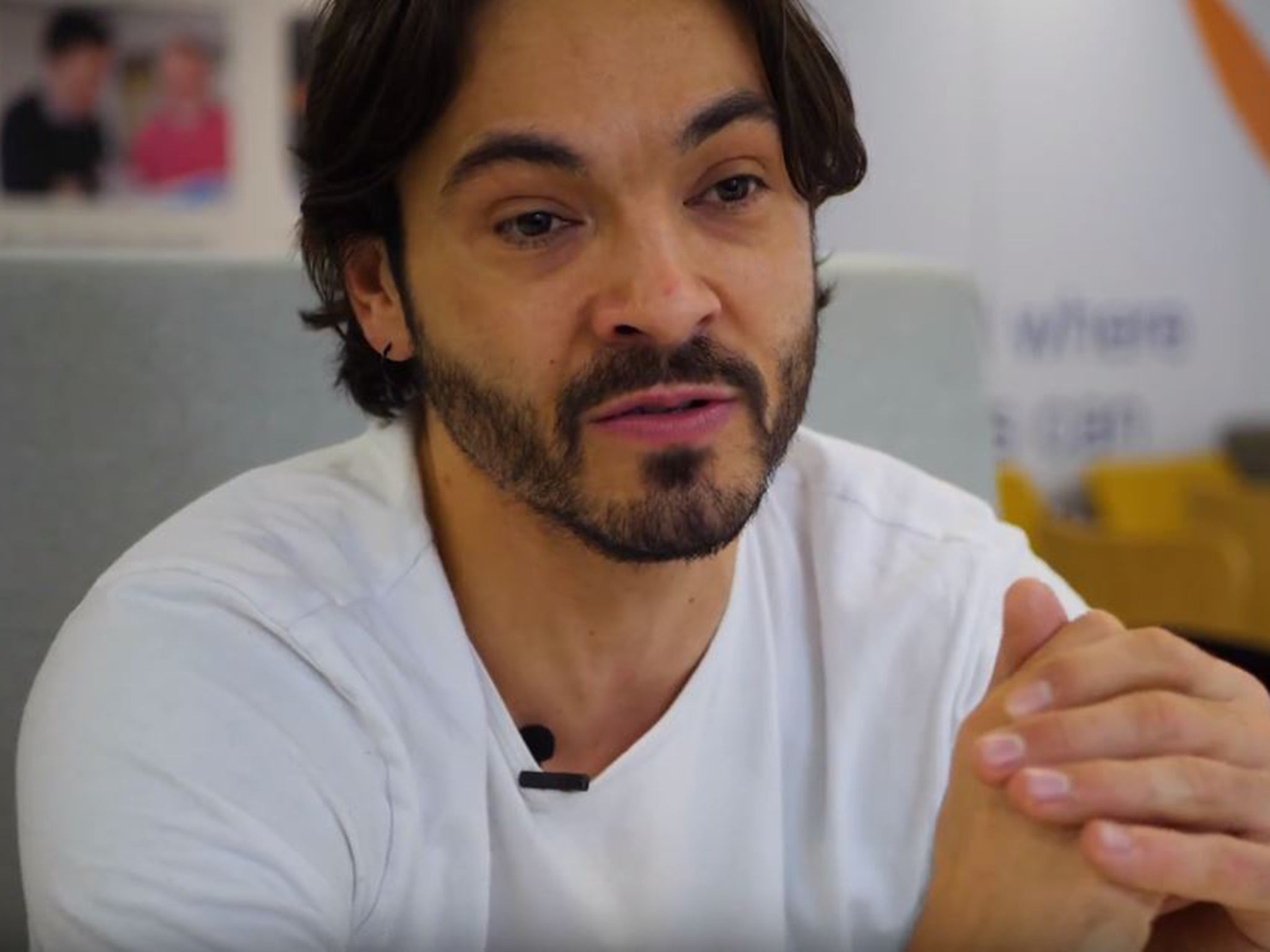

Jonsel Gourkan feels the same way. He’s got several years on Headley. But he’s also fit, with the sort of slim athleticism advertisers are fond of. He was, in a former life, a professional footballer with Galatasary, the club which is a regular contender for the Turkish title, and which offers one of the more frightening away trips for opponents in the Champions League.

Gourkan has since become a comedian, touring with a show entitled ‘Keep calm, I’m only diabetic’.

He says: “The name does need to change as both types are different, and they shouldn’t be classed as the same as one another with just a number to separate the two.

“We constantly have people asking ‘what type are you?’ What letter of the alphabet relates to your condition? Are you sure you have Type 1? I mean look at you, you have the physique of a sunbed bulb... This is all because of labelling diabetes with a type. It causes damage and creates a hostile atmosphere. It should be separated by having a different name.”

Gourkan has a very good reason for feeling this way. He doesn’t get warnings when his blood sugar becomes dangerously low, known as hypoglycaemia.

“I have suffered with hypo unawareness for over 10 years in a 29 year relationship with Type 1. Low blood sugar can be experienced by those who are also T2 and even people who aren’t diabetic, but T1s are much more prone to the problem and it can be extremely dangerous.

“Type 2 seems to be classed as the only type of diabetes that exists, and so most people don’t have a good understanding of what low blood sugar is, what it means for Type 1s, and how they could provide assistance. It’s something that needs to be addressed, and it explains why we need to ensure a better understanding of both types of diabetes.

“I have had ignorance thrown my way when stating I’ve had to go home to give myself an evening injection. I’ve even had a comment of ‘you brought this condition on yourself’ hurled my way. A two-year-old can get it. So these people are saying a two year old could have brought the condition on themselves? There’s no magic diet that can make the pancreas of a Type 1 work again.

“The way diabetes is promoted and talked about seems to make those that aren’t aware think that diabetes as a whole can be prevented and also cured. That’s just not true.”

Gourkan says this as someone who has close family members with both types.

The debate about whether changing the name(s) could help change attitudes has been around for several years.

In fact in 2013, Jamie Perez, an American mother of a son with Type 1 diabetes, won the support of 16,621 people when she and a friend launched a petition on change.org in an attempt to challenge the “ignorance and misconceptions” suffered by their Type 1 sons.

There’s no magic diet that can make the pancreas of a Type 1 work again

“It is time for new names, an end to misconceptions, uniquely focused advocacy and goal directed fundraising. We are not requesting a significant disease reclassification. We are simply requesting new names that properly reflect the nature of onset for Type 1 & Type 2, something not accomplished with numbers,” she wrote in support of the petition.

“The medical community should determine appropriate names, but as an example, the nature of onset for Type 1 would be reflected in a name such as Autoimmune Diabetes and the nature of onset of Type 2 in a name such as Insulin Resistance Onset Diabetes (IRD). A name change is not a monumental task. It has been done before. The time has come to do it again.”

Sure enough, Type 1 used to be known as “juvenile diabetes”, whereas Type 2 was referred to as “adult onset”.

Those involved in raising funds for research have privately told me that each type really requires different treatment teams, rather than having them pooled, and shouldn’t have to compete for the same pots of research funding, as they often do now.

Could a name change help with that?

The movement, such as it has, hasn’t got far beyond petitions (another making a similar point emerged from Australia just over a year after Perez’s and attracted more than 3,500 signatures) and discussions on internet message boards.

Charities in the sector remain equivocal.

Dan Howarth, head of care at Diabetes UK, recognises the problems created by the public’s ignorance, but believes it is best dealt with through education.

“We know that there is a significant lack of understanding about diabetes, particularly regarding the similarities and differences between Type 1 and Type 2. However, instead of renaming Type 1, education – for the public and for those working in healthcare – is a much more powerful tool in challenging the misconceptions that still surround this serious, complex condition,” he says.

“Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are both very serious conditions, and are associated with the same complications if not managed well. Everyone can benefit from a greater understanding of all forms of diabetes, which is why it is more important to educate and inform, dispel the myths which surround all forms of diabetes, and change the public’s perception of the condition, and how serious it can be.”

Michael Connellan, Head of External Affairs at JDRF, a charity that focusses on Type 1, says: “The debate on whether Type 1 diabetes as a condition should be renamed is complex, not least because it would require international consensus.

“We don’t take sides. Instead, we focus on the urgent need for greater research, recognition and understanding of distinct types of diabetes. The way forward is resources for greater education and awareness, research funding, and also better segmentation of clinical care. This is key to improving people’s lives with Type 1 diabetes.”

It’s worth noting that some Type 1s oppose changing the name.

Mike Hoskins, a blogger made that point, in a piece for Diabetes Mine. He argued that the change in the name from “Juvenile” and “Adult Onset” to today’s “Type 1” and “Type 2” has been a messy process, with several intermediate steps along the way.

I just don’t see the value of investing our efforts, time and money (yes, renaming incurs costs) in creating descriptive, scientific names for a cause we’re trying to make easier for the public to embrace, rather than more difficult

He argues that it has done little to damp down the continuing confusion about the conditions and wonders whether another change would really help to resolve the problem, assuming the necessary international consensus could even be reached.

He is also sceptical about whether it would do anything to reduce the amount of rubbish appearing in the media. As someone working in that sector, I regret to say that he might have a point there.

Hoskins central point? “I just don’t see the value of investing our efforts, time and money (yes, renaming incurs costs) in creating descriptive, scientific names for a cause we’re trying to make easier for the public to embrace, rather than more difficult.”

Where I differ with him is that in fostering the debate about the name, in campaigning and giving it greater prominence, we might be able to draw attention to the problems being caused for both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics.

It should be said that this is not about those of us with Type 1 trying to throw our Type 2 friends and fellow patients under the bus. Far from it. It’s about fighting to make life better for both types.

With NHS England’s callous and sickening description of glucose testing strips and needles – things that people like me depend upon for our lives – as “low priority” medications in a recent press release, fighting is something we are clearly going to have to do a lot more of.

Hoskins pointed in his blog to the following, posted by another Type 1 diabetic. It’s worth reproducing in full because it’s very good.

“I want diabetes advocates worldwide to pledge:

“To have empathy, no matter the type.

“To advocate for those with this condition, whatever the type.

“To educate about diabetes, regardless of the type.

“To correct misinformation and stereotypes that are so common in society and the media.

“To recognise the hurt that misinformation and stereotypes cause people everyday. Hurt that is both emotional and physical.

“To help people, who for whatever reason are affected by these stereotypes on a daily basis. People who just happen to live next door, who just happen to come to your family picnics, who happen to be among those you care for. People you’ve never met, people with families and loved ones.

“People who happen to have diabetes.

“Because we are all people.”

Yes. Yes and yes again. But we’re a long way from that.

Language has power, and the language surrounding diabetes is bad. A task force, consisting of representatives from the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) last year concluded that “the use of empowering language can help to educate and motivate people with diabetes, yet language that shames and judges may be undermining this effort, contributing to diabetes distress, and ultimately slowing progress in diabetes outcomes”.

It continued: “The time has come to reflect on the language of diabetes and share insights with others. Messages of strength and hope will signify progress towards the goals of eradicating stigma and considering people first.”

I understand why people disagree, but I’m among those who believe that a name change could and should be part of that. I also believe it would serve the interests of those of us with both Type 1 and Type 2. Or with, say, Autoimmune Diabetes and Insulin Resistance Onset Diabetes.

But I believe diabetics themselves should take more control of the debate, and not to have to wait for decisions to be made by the scientific and medical professions.

One thing that unites Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes is that the condition can leave one feeling powerless and very low. Media campaigns, and bullying, sometimes from medical professionals, only add to that.

Change is desperately needed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments