How the world of death and funerals has become fashionable through digital culture

‘Tearleading’ – the process of publicly sharing condolences after someone famous has died – has become an internet phenomenon. It’s made grief trendy and has digitised the only one true certainty in life: death

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

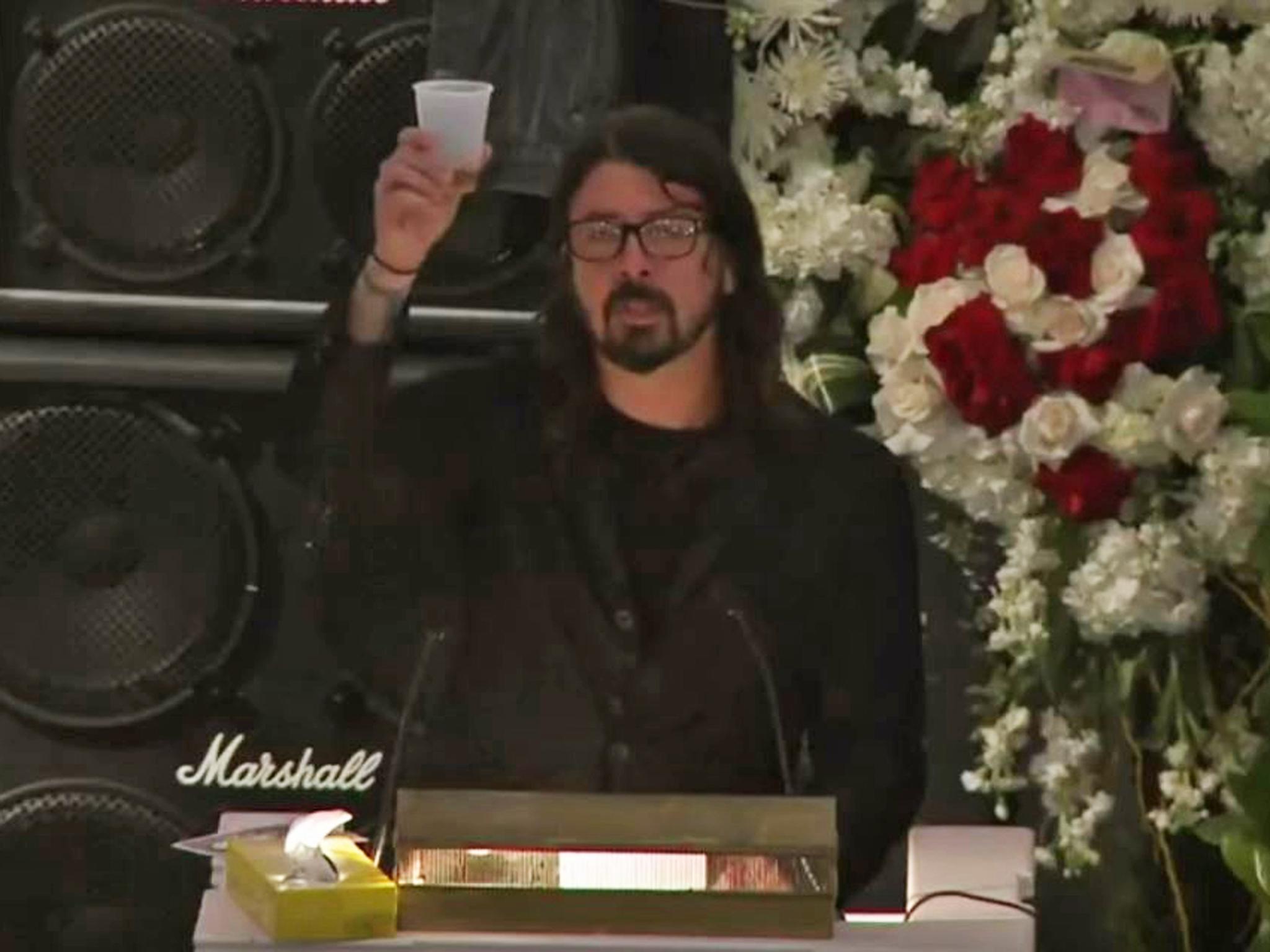

Your support makes all the difference.It’s one of the more blood-curdling things about Facebook – the social media death notice. You know the score: the recently deceased star of Top of the Pops, sitcom or stage is commemorated by way of a YouTube video and a deluge of weepy RIPs and “part of my life” eulogies, a phenomenon derided as “tearleading”. The high-water mark for this was who “taught us how to live, then taught us how to die” two years ago.

Of course, entrepreneurs have noticed this spectacle, which writer and psychologist Elaine Kasket brackets as “the data of the dead”. It’s part of a digital-led revolution in dying and death and it’s changing the way we see people pass into the ineffable digital afterlife. “We’re developing an entirely new mentality about death and dying,” she says.

Kasket (yes, she knows) is the author of an upcoming book about digital death called All the Ghosts in the Machine, and has observed a huge rise of interest. “I was at a recent SXSW festival and was introduced to someone who put on a super-serious voice and told me: ‘I’m in the death-tech space’.” As a subject, dying has become fashionable, with investors pouring money into startups, bolstering thought leadership and inspirational TED Talks on “new ways to think about death”.

There are so many new death-tech sites that they break up into different types. There’s the price disruptors like Harbour Funerals, Beyond.life, and Funeral Zone, which offer price comparisons and sometimes, TripAdvisor-type reviews. Derrick Grant set up Willow when a close friend couldn’t afford his funeral expenses and found one-sixth of Britons struggle to pay for a funeral – the average cost of dying is £8,905. He now offers an against-deadline price check to help those who “couldn’t afford to die”: the ultimate poverty. “I found the industry hadn’t changed for 100 years,” says Grant. “People thought you had to pay a lot to do right.” Now it’s becoming more transparent, more open, and partly as a result, says Grant, “funerals have become less funereal”.

Then there are the planning sites, which include Cake, a US company that has developed an app for end-of-life planning, and the UK’s DeadSocial.org which explains how to prepare your digital estate from the scattered confetti of Instagram, Facebook, Gmail et al. On SafeBeyond, users can create an online cache – including video and audio messages – to be shared posthumously with loved ones which founder and chief executive Moran Zur has called “digital relics” and “emotional life insurance”. My Last Soundtrack will develop your end-of-life Spotify playlist. More than half a million people die every year in the UK, and market analyst IBISWorld says the UK funeral sector is worth £1.7bn. No wonder there’s been significant funding from angel investors in that “death-tech space”.

This stuff enthuses Peter Billingham, a celebrant and “digital death adviser” who founded the website Death Goes Digital. “The world of death and funerals has really been disrupted by digital culture,” he says. “What was stable for hundreds of years has changed enormously in the last five years. We’re more open about death than ever before and technology is helping to reframe what death means.”

Baby boomers, now moving into the death demographic, are leading the way. Milestones include the 2016 livestreaming of funerals, including those of Lemmy Kilmister and Céline Dion’s husband René Angélil; and of course Bowie, who as ever in the avant-garde, favoured a direct cremation, where the body is cremated before the funeral. There’s a growing inventiveness in eco-death options too: recomposition, where the body becomes compost, and aquamation, a kind of a water cremation – even a “mushroom burial suit”. There are death celebrities, notably Caitlin Doughty, a “mortician and activist” who founded “death acceptance” collective The Order of the Good Death, spearheading the “death positive” movement.

But it is the tech spiritualism that is perhaps the most fascinating part of the digital death otherworld. Many readers will recognise the curious and unsettling scenario whereby a dead friend or relative pops up zombie-like on Facebook, perhaps in a prompt to recognise a birthday.

This has led to a huge leap in the way we approach the afterlife. In the past, says Elaine Kasket, attitudes to the dead divided into two main global tendencies: cultures of memory, and cultures of care, roughly zoned into west and east: in China, for example, there’s a tradition of believing that one’s ancestors remain active, while here we honour their memory with photographs and grave visits.

“Now, with digital culture the dead are becoming more vocal and socially influential and the West is moving towards a care culture,” adds Kasket. “They are increasingly in the places of the living.” Digital representations of dead persons won’t be confined to cemeteries. They will haunt different spaces: perhaps even become a rights lobby: the “transdimensional”, perhaps. They will be what Kasket calls the “active dead”, and what Billingham calls “present not absent”. Many people have online conversations with the dead on Facebook, which introduced a legacy contact option in 2015, and Billingham says that we’re already seeing the emergence of a new kind of professional: the “posthumous legacy curator”.

There are far reaches of death-tech that encroach upon sci-fi. Eternime, founded by MIT fellow Marius Ursache, is about creating an eternal posthumous avatar: animated by your digital footprint and given life by artificial intelligence, and is building a database of like-minded people who gain the chance for grandchildren to interact with their unmet great-grandparents. Also in the US, Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad, a computer scientist and specialist in personality emulation, is engaged in a project to create simulations of the dead people so as to keep our loved ones “alive”. These avatars will start on the screen, move into virtual reality and augmented reality, then potentially become life-size simulations. Ahmad, who was inspired to work in the area when his father died, sees it becoming reality between 2030 to 2050. “It’s not if, it’s when,” he says. And to those who say it sounds like Black Mirror: well, go back and have a look at the “Be Right Back” episode.

Ahmad thinks that cultures like Japan, with its animist traditions and a neophilic acceptance of robots, will be the early adopters. But he doesn’t see why (bar a few surmountable religious barriers) it shouldn’t take hold everywhere as we become used to it. “It means my daughter will have the chance to interact with my father,” he says. “It will deepen our relationships with our dead loved ones and offer a living memorial that can bring ‘emotional enrichment’.” We’ll be less likely to visit graves, perhaps, and more likely to summon Gran like a digital Doris Stokes.

Of course Ahmad has critics. “People bring up the idea that we need ‘closure’,” he says. “But it goes towards solving the ‘if only I’d said this or that’ problem to an extent.” Still, he concedes there are plenty of legal and ethical issues. What if the simulation were sanitised, with difficult opinions edited out? How should their ageing be represented? Does their voice sound right? Ahmad thinks that the development of digital trusts will emerge, and with artificial voice synthesis, the latter will get better. “But these are uncharted territories. It will affect the way we see identity. Adding emotions may be a challenge.” Will Death 2.0 bring on unintended consequences? It’s a dead cert.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments