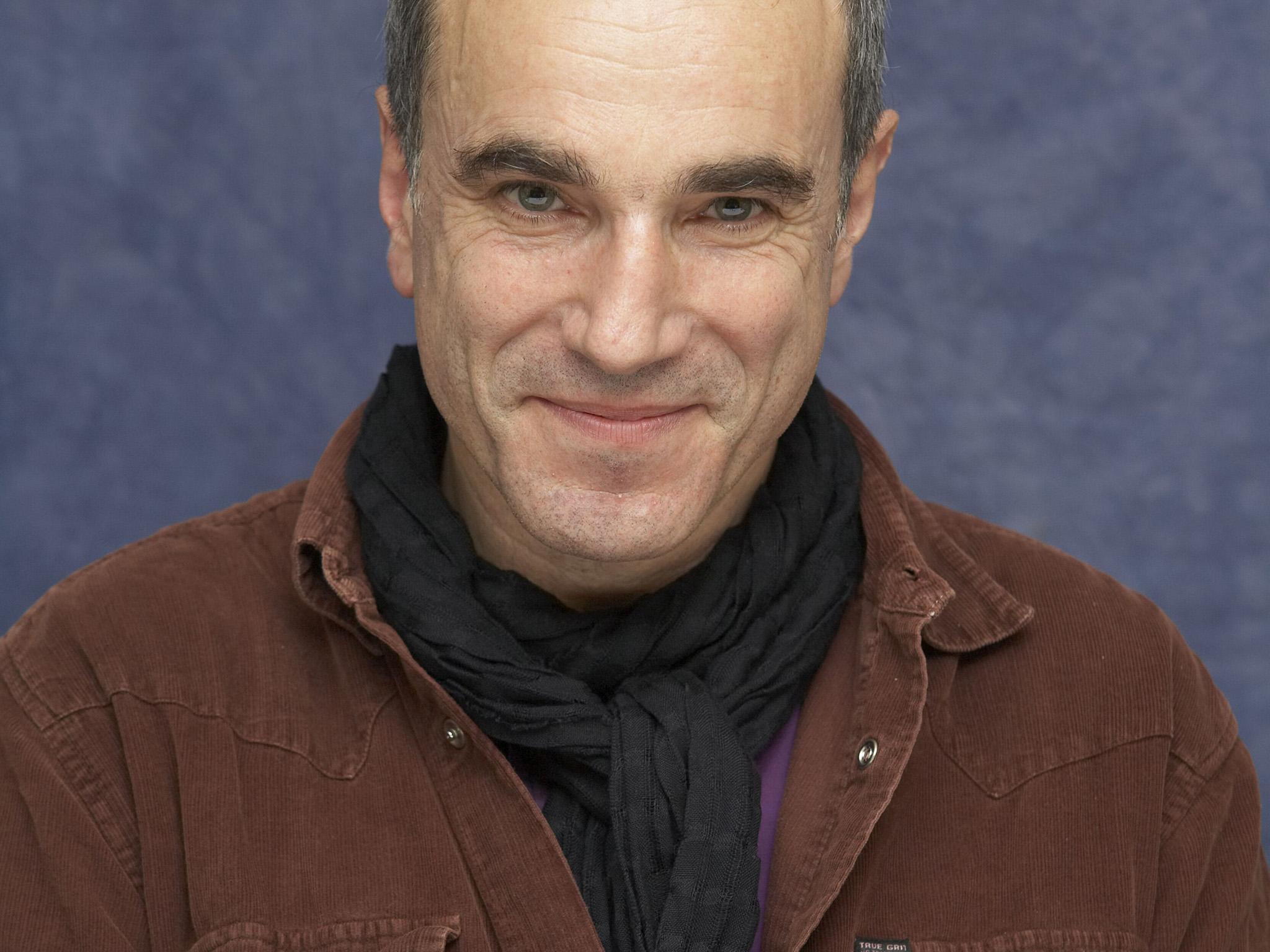

Daniel Day-Lewis retirement: Isn't it a bit premature?

The actor who won three Academy Awards for Best Actor for his performances in ‘My Left Foot’, ‘There Will Be Blood’ and ‘Lincoln’ has announced his retirement at the age of just 60

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Daniel Day-Lewis, who has announced his retirement from acting, has never been the type of actor who could give an off-the-rack performance. All his work has been bespoke. It’s a tortuous metaphor but a fitting one considering that he once took a break from acting to work as a cobbler and that his final film role is in Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film Phantom Thread, set in the couture world of 1950s London.

Those who’ve worked with Day-Lewis often still sound vaguely astonished years later when talking about his painstaking approach to any given role. Take Martin Scorsese’s Gangs Of New York, in which he played Bill “the Butcher”. Cutting, the very dapper, very vicious leader of a street gang in mid-19th century New York.

“Daniel got so deep into his performance that he had a British butcher come to teach him how to cut meat,” Scorsese told author Michael Henry Wilson. “It became his whole world. When the sequence came in which he kills Monk from behind with a meat cleaver, he told me” ‘I should have sent him a little signal. Suppose I send him a pig’s head.‘ An excellent idea! He was thinking like Bill!”

Irish filmmaker Kirsten Sheridan was a 12-year-old when Day-Lewis appeared in the first of his three Oscar-winning roles, as the handicapped writer-painter Christy Brown in her father Jim Sheridan’s My Left Foot. She was on set for much of the shooting and years later still expressed awe and bewilderment at the lengths to which Day-Lewis went to play his role. “He’d call you by your film name, and you'd call him Christy. It was madness. You’d be feeding him, wheeling him around. During the entire film, I only saw him walking once,” she recalled.

There are plenty of similar stories from collaborators on Day-Lewis’s other films. He has worked with some famously demanding directors – Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Michael Mann, Philip Kaufman, Paul Thomas Anderson – but he has trumped almost all of them in his level of dedication. Much of his preparatory work hasn’t been strictly relevant. He didn’t really need to learn how to build canoes to play Hawkeye in Last Of The Mohicans or to learn how to speak Czech for his role as the womanising brain surgeon in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Czech-set but made in English). His theory, though, was that you had to become the character you were playing: dress like him, move like him, think like him.

Day-Lewis slept in jail in the build up to playing Gerry Conlon In The Name Of My Father. It goes without saying that when he starred in Jim Sheridan’s The Boxer, he started preparing two years beforehand, working out in the gym with former world champion Barry McGuigan. Equally predictably, he became so skilled in the ring that McGuigan said he was the equal of most of the professional middleweights then competing in the UK.

Generally, when actors are “up themselves”, they’ll tend to be mocked. According to movie lore, Dustin Hoffman was told by Laurence Olivier to “try acting” rather than staying awake for three days in a row in order to look suitably downtrodden and exhausted for his role in Marathon Man. But no one has offered those kind of put-downs to Day-Lewis. He demands respect. He is the actor as auteur, working as much to offer his own vision as to serve that of the director. When one interviewer asked him about the Olivier/Hoffman story, he turned it on its head, interpreting it as being far more revealing about Olivier’s shortcomings as a screen actor than about Hoffman’s obsessiveness. “He [Olivier] is missing the point there, he is just missing the point.”

One downside of the famous Day-Lewis intensity is that he has never really done comedy. There have been some lighter roles along the way, for example the very precisely observed performance as the pinched and uptight Cecil Vyse in Merchant-Ivory’s Room With A View. There’s also a humour and playfulness to his role as Johnny, the punk with the right wing past, in Stephen Frears’s My Beautiful Laundrette. With his big moustache and top hat, he brought a lycanthropic flamboyance to his role as Bill the Butcher in Gangs Of New York. His performance as wealthy lawyer Newland Archer, falling in love with Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), an older woman with a chequered past, in Scorsese’s The Age Of Innocence, suggested he could very well play romantic leads if inclined – but that clearly wasn’t ever his intention.

What is surprising is that Day-Lewis didn’t study with Lee Strasberg or Stella Adler. He’s not American. He wasn’t brought up on Method acting. His thespian grounding was at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, whose alumni include such figures as Brian Blessed and Ian Lavender (Pike from Dad’s Army). “The prevailing opinion is that I am mad,” he said in one interview when reflecting on the way he worked.

Several of Day-Lewis’s greatest performances have been as Americans. You can see his Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood and his Abraham Lincoln in Spielberg’s Lincoln as providing twisted reflections of one another. In the former, as the oilman who strikes it rich, he embodies the darkness and covetousness that can go hand in hand with the American dream. In the latter, he plays an idealised version of Lincoln, graceful, sensitive and very astute. It’s the kind of role that Henry Fonda or James Stewart would have played a generation before but he brings a psychological complexity to Lincoln that they would have struggled to match.

“I can’t accomplish a goddam thing of any human meaning or worth until we cure ourselves of slavery and end this pestilential war,” the President rages in a strangely high pitched voice as he tries to persuade his colleagues to pass the 13th Amendment. This is Lincoln done Method-style. Day-Lewis plays the President as an admirable but tormented figure. His vulnerability and doubt make him all the more convincing.

So what for Day-Lewis now? Is he going to spend the rest of his life making shoes? The retirement really does seem premature. He’s very stubborn in the extreme but we can only hope that this is one decision he is prepared to reconsider.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments