The tyrant who advocated for the poor: how Fidel Castro’s life and rule is a political paradox

The US opinion of Cuba’s former leader is widely unfavourable, but elsewhere he has been praised for improving the lives of ordinary Cubans. Mick O’Hare examines the dichotomy of his rule

Popular uprising or roughshod revolution? Political insurgencies rarely fail to create paradoxes. The contradictions inherent in the notion that one person’s freedom fighter is another’s terrorist are pretty much irreconcilable. We can be certain the newly emancipated French peasant of 1789 felt differently about recent political developments than the dissident Jesuit staring face down into a basket in front of the Paris mob.

“My grandmother danced around the table,” says Maria Gutierrez, speaking of the time when Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement seized power in Cuba 60 years ago, in January 1959. What would ultimately morph into the Communist Party of Cuba had ousted corrupt, authoritarian dictator Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar – who had held power for a quarter of a century. Maria also remembers her grandmother, head in hands, sitting at the same table when, 17 years later, Maria’s uncle – her grandmother’s son – was arrested. “He ran a printing press,” says Maria. “Although he was unaware, people opposed to the government had printed leaflets on the night shift which questioned peacefully Cuba’s political direction.” Maria’s uncle would return home, but he was a cowed man. “He never told us what happened, but he never smiled and whenever a door shut he jumped in fear.”

When Castro resigned as first secretary of the Central Committee, handing power to his brother Raul in 2011, he was the longest-serving non-royal de facto head of state in the world and had ruled for 52 years. When he died in 2016, outwardly a nation mourned, yet inwardly there was introspection.

For, according to the Cuban state, not only had Castro been the father of the socialist revolution that overthrew the Batista regime, he led a popular uprising of the downtrodden. The October Revolution of 1917 was as much a Bolshevik military coup d’etat as a people’s rebellion, and the rise of communism in Vietnam or Cambodia, opposed by sections of the population, had led to civil war. But Castro was there by popular mandate. Cubans had been worn down by the corruption, brutality and indifference to their plight shown by Batista. His regime supported itself through links to organised crime in the US, a throwback to the days of rum smuggling during prohibition, and by allowing American companies to dominate Cuba’s traditional industries such as sugar and tobacco. Castro freed his nation and, according to the Cuban state, his legacy was sustained and secured as he stood pluckily against the might of the United States’ political machinery.

How much of this is true, as ever, depends on which side of the divide one sits, but it’s fair to say the circumstances that brought Castro success owed much to his charisma and his opposition to a government that was not working in the interests of the Cuban people.

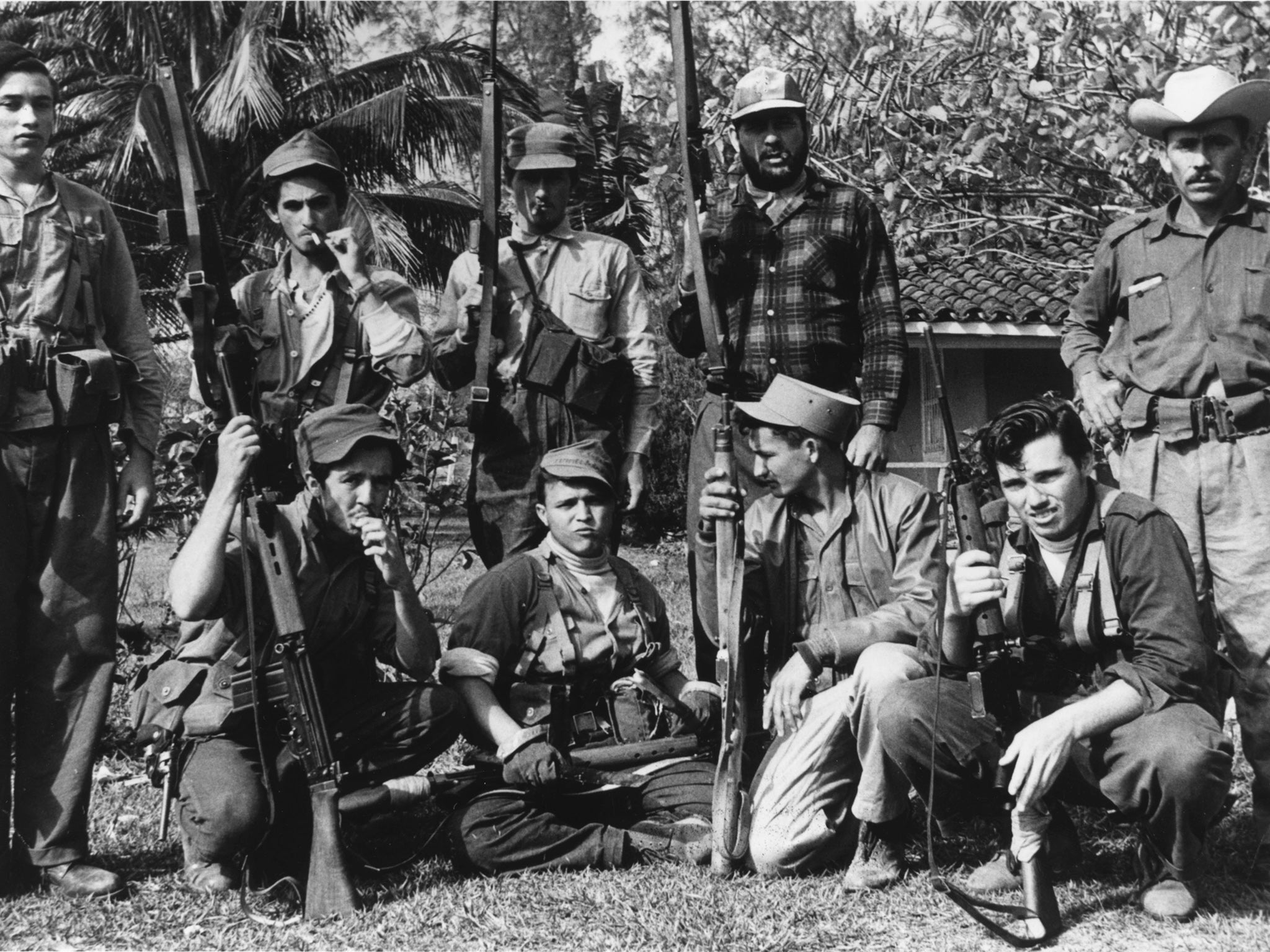

Castro first attempted to seize power, alongside his brother, on 26 July 1953 – hence his eponymous rebel movement – but was imprisoned and then exiled in Mexico. When he and Raul returned in 1956 declaring “we will be free or we will be martyrs”, alongside charismatic Argentinian revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara, he was again defeated by government forces – The New York Times even reported his death – and fled to the Sierra Maestra mountains. From there Castro conducted an insurgency that slowly gained the support of the wider population of Cuba, especially after Batista postponed the 1958 presidential election. Opponents were arrested and tortured, and unemployment and poverty were rising.

Even at this early stage though, Castro himself recognised the benefits of sowing fear. He threatened candidates and voters in the rescheduled election and some areas saw negligible turnout. Yet when the results unexpectedly returned Batista’s favoured candidate Andrés Riveroi Agüero, the government had essentially brought about its own demise. People considered the election rigged, and support for Batista collapsed. When 12,000 government troops failed to oust Castro from his strongholds, the insurgency pushed home its advantage. In the early hours of 1 January 1959 Batista fled, ultimately to the Portuguese island of Madeira where he would die.

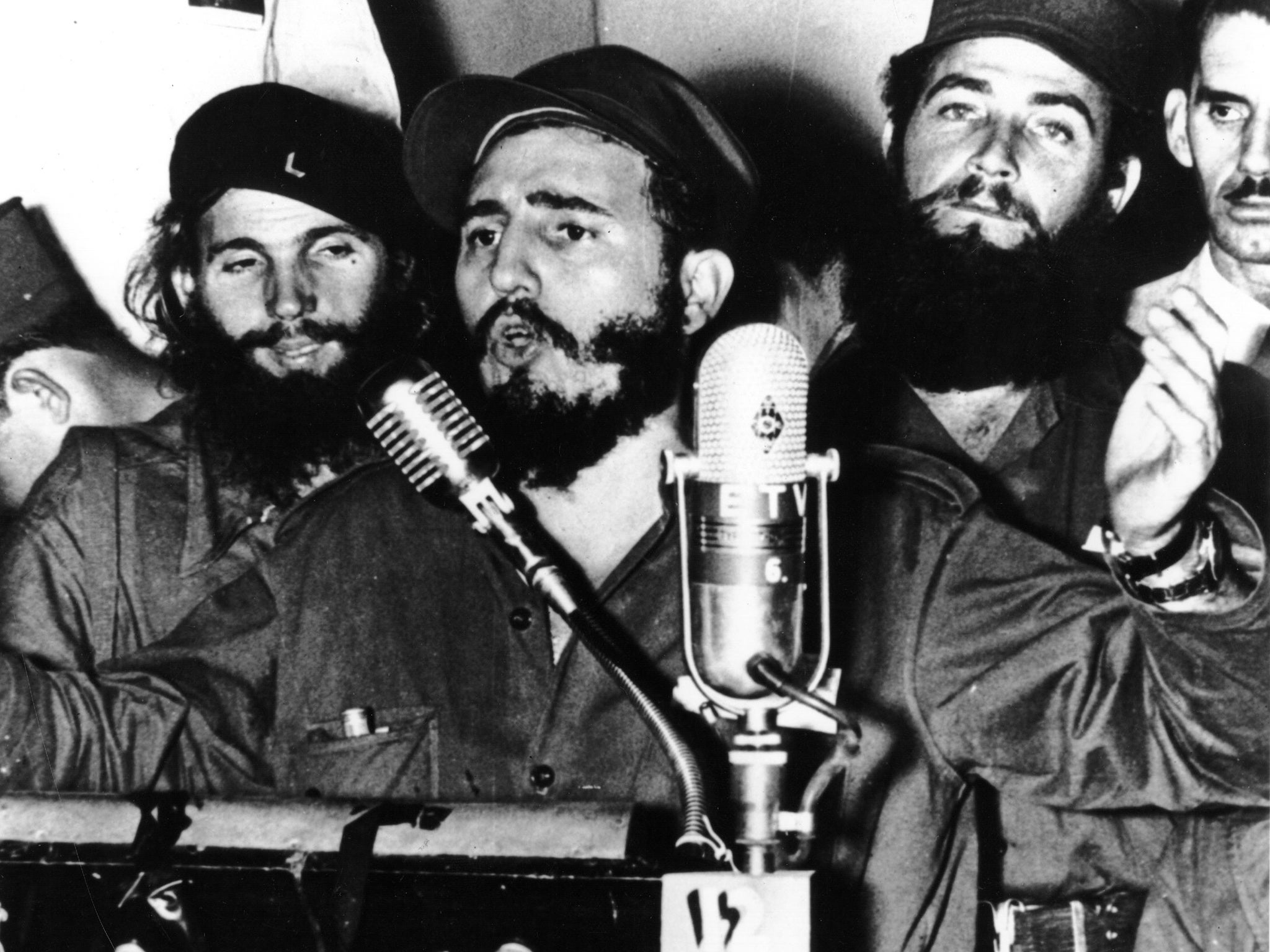

On 8 January, Castro marched into the capital Havana and formed a new government which, initially, was more Cuban nationalist than communist. At that juncture, Castro knew more what he liked than disliked and was still being feted in the US. He travelled there in April 1959, meeting vice president Richard Nixon and the American Society of News Editors, before which he declared that he and his government were “not Communists”.

Initially the US had tentatively supported the overthrow of the Batista government and at this stage Castro had not begun nationalising American business interests in Cuba. But it was also clear that the Cuban population had been buoyed by his promises of land reforms for the peasant class and his declaration of equality for all Cubans. He took on organised crime too, closing down casinos, nightclubs and brothels run by the American mafia and frequented by American tourists. It was a popular stance, although not among the criminal classes. Notorious mobster Meyer Lansky, who had to flee Cuba, said Castro “ruined” him.

In 1960, the Soviet Union’s deputy premier Anastas Mikoyan visited Cuba to sign a trade agreement, and a programme of nationalisation of American and foreign investments began. Although it wouldn’t be until 1965 that Castro fully declared allegiance to Marxist-Leninism and his 26 July Movement became the Communist Party, the US began to impose diplomatic and economic sanctions. The Soviet Union quickly stepped into the gap. Castro embraced Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev at the United Nations General Assembly in September 1960 and the USSR began supporting the island economically and militarily.

The following year, the United States ham-fistedly attempted to overthrow Castro by backing a band of US-based Cuban exiles. The anti-Castro rebels landed at the Bay of Pigs on Cuba’s south coast. The invasion was a huge failure and it cemented Castro in power as the leader who had seen off the imperialist invaders. Believing that the Cuban people would rally behind the Bay of Pigs invaders, the CIA vastly overestimated the desire of Cubans to be “liberated”. Instead, Castro proclaimed Cuba to be a socialist state. The people were more unified than ever behind him and the botched invasion would also precipitate one of the most dangerous crises the world has witnessed.

In October 1962, a US spy plane spotted silos being built on Cuba, awaiting the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles. Florida was only 90 miles away. The Soviet Union said they were a response to both the Bay of Pigs and American missiles based in western Europe. Despite members of his inner circle advocating an air raid, US president John F Kennedy was more measured and imposed a naval blockade of the island even as Soviet ships sailed towards Cuba carrying more missiles. A confrontation between the two nuclear superpowers seemed inevitable. “I thought it was the last Saturday I’d ever see,” said US defence secretary Robert McNamara, of 27 October. But wise heads prevailed. In return for the US agreeing never to invade Cuba again (and, we later learnt, to remove US missiles from Turkey), Khrushchev withdrew the warheads. Once again Castro was seen as the champion of his people as he stood with his Soviet allies against US aggression.

Already, though, the contradictions were apparent. Even as reforms were being made to better the lot of the Cuban working class, those people identified as being linked to the Batista regime, including prisoners-of-war in contravention of the Geneva convention, were being tried, imprisoned and executed. Many may have been guilty of crimes against humanity but their trials lacked legal credibility.

On the other hand, throughout the 1960s, Castro’s government introduced socially progressive reforms. There was equality for black Cubans (making Castro something of a totem for the US civil rights movement) and women’s rights were enhanced. The entitlement to education, medicine and housing was enshrined in law. By the end of the decade all Cuban children attended school, unheard of before 1959. Illiteracy was virtually eliminated and access to arts and sport opened up to the wider public.

These contradictions have led to a dichotomy in how Castro and the revolution are viewed around the world. In the US, opinion is widely unfavourable, but elsewhere Castro has been praised for improving the lives of ordinary Cubans. Prior to embracing communism, his aim was to bring sovereignty back to Cuba and to eliminate poverty and inequality. Born into a Havana slum in 1954, Eva Perez-Sainz says: “I was the first in my family to go to proper school. When my father broke his leg at work, he had it fixed for free by state healthcare. Nobody paid a bribe or risked a backstreet doctor. To us, it was astonishing, wonderful.”

But these achievements went hand in hand with curtailing the rights of some, a number that grew with the passing years. Suppression of free speech, detention of political opponents and journalists, suppression of religion, prohibition of foreign media and – as time passed – Cubans’ standard of living resolutely failing to rise, meant in some quarters support for the regime waned. And let’s not forget, as historian Andrew Roberts pointed out: “Hijackers and terrorists of all ideologies yelled the phrase ‘take me to Cuba’,” whenever they were about to face justice. The Castro regime seemed determined to offer sanctuary to people of questionable doctrine.

Foreign travel was generally outlawed but when, in 1980, hoping to flush out dissidents, Castro briefly allowed emigration for anybody who no longer wished to stay, 125,000 were so desperate they risked their lives in ramshackle boats. From popular insurgent to losing his people in just two decades? “Castro seems to provide proof of Lord Acton’s dictum: ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’,” wrote Mark White, professor of history at Queen Mary University of London.

But Castro clung on even after the 1991 demise of the Soviet Union and the end of its economic support led to famine. During what became known as Cuba’s “special period in time of peace” food was severely rationed as fuel and medicine shortages took their toll. Death rates increased and protesters took to the streets. Only the rise of fellow socialist Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, who became a key economic partner, and the reintroduction of trade with Vladimir Putin’s Russia saved the regime.

Felipe Garrido worked in the Cuban civil service until retiring to live with family in Venezuela, inadvertently, it seems, swapping one political maelstrom for another. “Like Chavez here,” says Garrido of his adopted home, “Castro was hugely popular, especially among the old, even during the special period. Both stood up for people who had nothing. I don’t deny Castro’s regime could be merciless, but he had a superpower 150 kilometres away which wanted to blow our island out of the water. He had to be watchful.”

But even an old supporter like Garrido realised Castro changed as he aged. “He wanted to cling to power,” he admits. “So he played up this image of the defiant ruler in military fatigues, chomping on cigars and haranguing the US who wanted to steal his revolution. Like your man Churchill, cometh the hour, cometh the man. They served their nation in crises but were both flawed.”

So the paradoxes remain. Although she is long dead, and despite what happened to her son, Maria Gutierrez believes her grandmother still had vestigial faith in Castro’s Cuba – she could remember Batista. Gutierrez is more ambivalent. “I’m no apologist for capitalism,” she insists. “But show me a socialist state that doesn’t end up locking up its people to make it work.”

Yet there are people in Russia today who lived through the Second World War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the appearance of the free market economy in its multifarious forms, who still yearn for the certainties of the Stalin era. In 1980, Zimbabwe rejoiced at the election of Robert Mugabe, instrumental in overthrowing white rule. Yet hindsight has offered a different perspective. But hindsight wouldn’t be so named were it available in the first place. Freeing one part of the population may have the corollary of oppressing another. Can any political system not be accused of something similar?

Which is where the legacy of the “popular uprising” starts to become murky. Is there, in fact, such a thing? If a majority of people support it, and continue to do so, then it is arguably so. However, if sustaining that majority necessitates imprisonment, torture and worse, the legacy is undermined if not totally dismantled.

But what nation wouldn’t take steps to defend itself? The Cuban state estimates, although it’s impossible to verify, that Castro survived more than 600 plots to overthrow or assassinate him, some backed by Cuban exiles in the US, or the CIA, but many carried out by his own people. Yet even prior to these, the regime had introduced Committees for the Defence of the Revolution, local organisations that kept records of neighbours’ “suspicious” behaviour and watched for “counter-revolutionary activity”. Not the mark of a society dedicated to freedom of expression or association. Why free your people only to imprison those who disagree with how that freedom is being applied?

And the lessons for today? We are still living with the consequences of 1959, the Bay of Pigs and the missile crisis. After years of détente during the Barack Obama presidency, in which the US leader became the first sitting president to visit communist Cuba, the stand-off has ramped up again. The current incumbent of the White House lacks the diplomatic abilities of Jack Kennedy (or, indeed, Nikita Khrushchev) and is himself a populist leader, with an apparent mandate from the people, known too for his nationalism and indelicacy. Unlike Cuba in 1959, America is a mature democracy but one thing is certain, intransigence is only a vote winner for so long.

It is fair to argue that at the outset, Castro’s overthrow of an authoritarian dictator had popular support among Cubans that continued while life for most improved. But as US sanctions bit and relative poverty returned, what sustained the revolution even more was state oppression. “Simultaneously, he was an advocate for the world’s poor, and a petty and compulsive tyrant,” wrote Julie Bunck, professor of political science at the University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Perez-Sainz concurs: “In the US, Castro is often placed alongside the names of Hitler, Stalin and Pol Pot. That’s ridiculous, at the outset he was different, I wouldn’t have been educated without the revolution. But – and I hate saying this – as time passed things changed.”

So 60 years on: popular uprising or uncompromising totalitarianism? It’s impossible to answer and depends on who is doing the answering. Castro embraced Nelson Mandela and Ernest Hemingway, but embodied the better traits of neither. He overthrew an oppressive dictator and saw off a bullying neighbour, then adopted the worst traits of both. It seems Felipe Garrido was right. There are two sides to every coin – bad penny and shiny peso.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks