‘Every threat counts’: A Columbine High School security officer prepares for the worst

In the Denver suburbs, the district has built what is likely the most sophisticated school security system in the US. Jessica Contrera talks to John McDonald, who’s in charge of overseeing it all

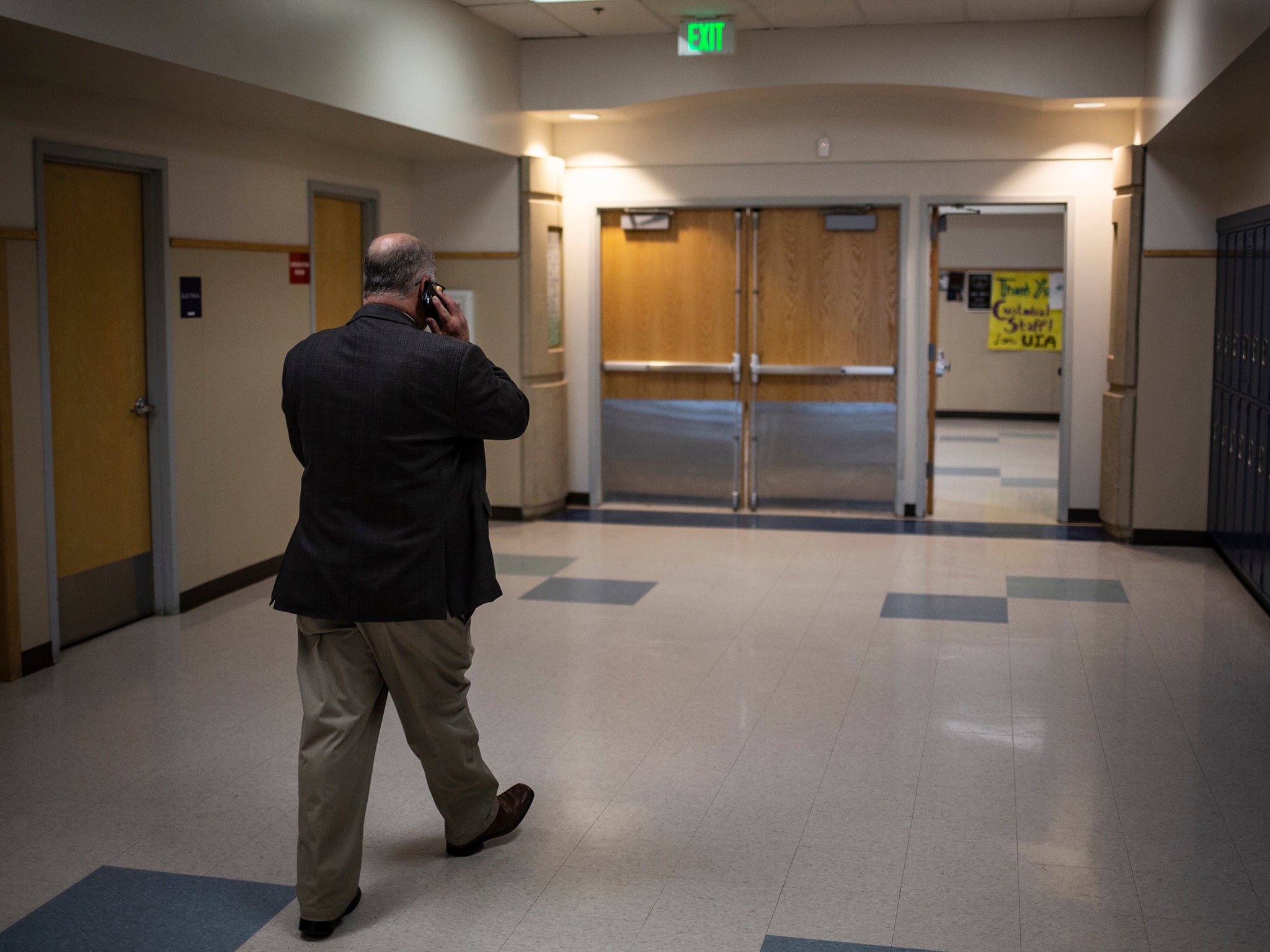

Before the call came, John McDonald had finished his breakfast of Diet 7Up, put on his uniform and tucked his Smith & Wesson into its waistline holster. He made it to his office at Jefferson County Public Schools in the US, where he is in charge of safety and security for a sprawling district that includes Columbine High School. On this morning, he even made it to his earliest meeting. And then his phone rang.

He knew as soon as he answered: the first school-shooting threat of the day had arrived.

“What do you got for me?” he says, and then he listens to find out how bad this one is going to be.

In a nation always awaiting the news of another school shooting, no community may be braced for that threat quite like the one surrounding Columbine High, a place forever defined by the 1999 attack that killed 13 people, wounded 24 more and ushered in an internet-fuelled era of mass violence. Twenty years later – the anniversary of the shooting is April 20 – Columbine is constantly invoked as the first name in the ever-growing list of campuses turned into crime scenes. Columbine, Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, Parkland, Santa Fe – each addition a reminder that this could happen anywhere, any time. Almost as if it were impossible to stop.

But all the while, Columbine has been figuring out how to do just that.

Here in the Denver suburbs, the district has built what is likely the most sophisticated school security system in the country: installing locks that can be remotely controlled and cameras that track suspicious people; setting up a 24-hour dispatch centre and a team of armed patrol officers; monitoring troubled students and their social media; getting training from world-renowned psychologists and former Swat commanders; researching and investing, practising and re-practising, all to ensure that when the next significant threat comes, it is stopped before the worst happens again.

At the centre of it all is McDonald, a 50-year-old police officer turned security expert who took the top job here 11 years ago because his only daughter was going to attend Columbine High. Today, he is responsible for the safety of 157 schools and 85,000 students in a community that long ago stopped talking about a need for healing or forgiveness and started focusing on recovery and preparation.

The officer who called McDonald was stationed inside one of the county’s other high schools. It was a Tuesday in March, one month before the 20th anniversary. There was a rumour, the officer said, that someone was going to shoot out the school’s windows.

Without McDonald giving an order, everything he has put in place to respond to threats is already in motion. More officers have been dispatched. Areas are being searched. His team and the local sheriff’s department interview students, teachers and administrators until they feel certain there is nothing they have missed.

Because what McDonald has learned, what he has preached around the country is this: every threat counts. Even vague, unspecific ones. Nearly all past school shooters gave some indication of what they were about to do. They bragged to friends, wrote it in an essay or made what seemed at the time like just a bad joke. The teenage Columbine shooters did so. The next shooter likely would, too.

“If you say you are going to kill us, are going to blow us up, if you make a threat to harm us, we are going to believe you,” McDonald liked to say, but lately, following through on that vow has become increasingly difficult.

Already, the district is dealing with more anonymous tips than ever from Safe2Tell, the online system Colorado students and parents use to report anything of concern. On his phone, McDonald keeps photos of the pistols confiscated from students because of those tips: a 9mm in November, a .25 calibre in December, a Glock .45 in January.

And those are just the internal threats. With the anniversary approaching, the intense and sometimes disturbing interest in Columbine that has long festered on the internet is spilling into the real world with greater frequency. Every day, multiple times a day, people show up at the high school wanting to see it, photograph it and get inside it. McDonald’s team usually stops them before they can even step out of their cars. Some explain that they just want to pay their respects to the victims. Others claim they are in love with the shooters, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who killed themselves inside the school. Some say they have been reincarnated with the shooters’ souls.

More than 150 of these strangers are showing up every month. The planning for the anniversary was underway. And now there is one more threat to handle from one of the district’s own students.

“Keep me updated,” McDonald says before hanging up his phone. Each day, he drains its battery at least twice answering all the calls from people who trust him to keep this place safe. Each day is a test of whether all he has done to protect them will be enough.

The classrooms at Sandy Hook Elementary School where 20 first-graders were gunned down no longer exist. The residents of Newtown, Connecticut, voted to demolish the site and build a new school beside it, complete with a memorial garden where the classrooms had been. Within two days of the shooting in Parkland last year, Florida officials proposed doing the same to the freshman building of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High, where 17 students and staff were killed.

But when McDonald pulls into the parking lot of Columbine, the school before him looks nearly identical to the one in 1999. A new library has been built to replace the one where so much blood had been shed. But the two-story curved green windows that the world watched wounded student Patrick Ireland crawl through before he fell into the arms of first responders have been replaced with identical ones. The lockers inside stayed royal blue. The cafeteria pillars, which the shooters had tried to explode, remain in place.

“In ’99,” McDonald explains, “there was a thought at the time – and it wasn’t a wrong thought – that if we tear the school down, the killers will have won.”

He sometimes wishes they had chosen differently. “We didn’t ever envision what it would become 20 years later,” he says.

He waves to the security officers and radios his location into the dispatch centre, where his team is busy monitoring the officers investigating the first threat and sending other officers to the location of a second. While McDonald has been overseeing an elementary school evacuation drill, his phone buzzes with another Safe2Tell alert.

There was a thought at the time – and it wasn’t a wrong thought – that if we tear the school down, the killers will have won

A Jefferson County student has reportedly said she wants to shoot up her school.

The details of the threat make McDonald doubt it is true. “But, you never know until you look into it,” he says. An investigation is launched.

Despite a $3m (£2.3m) budget and a team of 127 people working beneath him, McDonald personally checks every Safe2Tell alert. Not all are threats. There are reports of suicide attempts, cutting, child abuse, academic cheating, drug use, alcohol bingeing – all the other problems that make schools such fraught places.

The overnight dispatchers have grown accustomed to McDonald calling at all hours to check that every report is being met with a response. His staff knows his jokes about all the weight he has gained since taking this job and how he doesn’t take sick days because he is saving them for a massive heart attack. They know he vacations only in the weeks when school is out.

McDonald lets people believe he is simply dedicated to preventing additional suffering in a place that has already endured so much. That, after all, is true, and far easier to talk about than what happened when he was 19 years old.

In 1989, McDonald’s older sister Christy was assaulted, strangled and stabbed to death by a stranger who broke into her condo. The man was caught, and while McDonald was attending the criminal hearings, he was also working to become a police officer. His sister’s attacker eventually killed himself in jail. McDonald became an expert in violence prevention and taught his daughter, now a law student, to check locks twice before bed.

He circles around the back of Columbine, parks his car and swigs his second Diet 7Up.

In the world of school safety, so many of the practices taught in 2019 have their origins here and in all that went wrong in this place in 1999.

The spot where McDonald parks is not far from where law enforcement had formed a perimeter around the school. Police did not go into the building until a Swat team arrived. Today, officers are trained to enter immediately and take down the shooter, even if it means stepping over bodies.

The radio McDonald is using to talk to dispatch also connects to the area’s other first responders and law enforcement agencies. Twenty years ago, schools, police and emergency medical services had no single frequency on which they could all operate, causing chaos.

They also didn’t have a blueprint of Columbine when they arrived, meaning many had no sense of the layout inside. Now McDonald keeps detailed floor plans of all 157 schools in his trunk, along with extra ammunition, a bulletproof vest, a sledgehammer and an emergency stash of Peanut M&Ms for his diabetes.

He steps out of his car and appears on one of the school’s dozens of security cameras. More were being installed before the anniversary. He enters through a door his dispatchers have the capability to lock or unlock. Each classroom he passes is equipped with a deadbolt that locks from the inside with a simple turn. No more teachers stuck in the hallway, fumbling with a ring of keys.

The students he passes are all trained in what to do if a shooter enters the building, and all 1,700 have received a handbook outlining what would happen if their own behaviour indicated they might be a danger to themselves or others. School officials perform hundreds of threat assessments a year, bringing Jefferson County students and their parents in to analyse their actions, social media posts and mental wellbeing. They may order students to check in with campus security on a daily basis, attend therapy or carry a clear backpack. The close monitoring sometimes continues even after a student graduates.

“Hey, how are ya?” McDonald says as he walks through the building, greeting people by name. One administrator sees him and asks him to come into her office. She has been getting more and more of those emails, she says.

“I know the feeling,” McDonald assures her. “I don’t know if you heard, but on Saturday, we had 24 show up.”

She doesn’t have to ask what he means. Everyone at Columbine knows about the “lookiloos”, as one dispatcher calls them. McDonald estimates that more of these gawking strangers have shown up at the school in the last four years than in the first 16 combined.

They come first thing in the morning and in the middle of the night. They come from other states and other countries. When they are stopped in the parking lot, it doesn’t take much questioning for the officers to figure out whether they are “Columbiners,” those obsessed with the massacre.

The Columbiners seek each other out online. They scrutinise investigation records, school blueprints and writings from the shooters made public. They know not only the victims’ names, but also the names of the students who were near them when they died, what was said in their witness statements and where those survivors are today. They know where the shooters ate and shopped. They have theories, so many theories, but McDonald believes that for the most part, they are harmless.

The problem is the ones who aren’t.

In 2012, a 16-year-old came to the school seeking an interview for his high school newspaper. He asked question after question about how the killers were remembered. Soon after, he was arrested for plotting to bomb a Utah high school. Last year, McDonald’s team stopped a brown-haired 23-year-old woman named Elizabeth Lecron in the parking lot and sent her on her way. According to federal prosecutors, she returned to Ohio, purchased black powder and screws and planned to build a bomb that would be used to commit an “upscale mass murder”. Lecron has pleaded not guilty, and her attorney has asked for most of the charges in her case to be dropped.

Similar to the shooters at Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook and dozens of other attacks, Lecron worships Harris and Klebold, investigators say. She frequently posted about them on the blogging site Tumblr, calling them “God-like”.

McDonald and others say false information about the shooters reported by the media in the early days after the attack – that they were social outcasts enacting their revenge – has emboldened those who fantasise about following in their footsteps.

“Just getting through the next month is going to be a Herculean effort,” he tells the administrator.

Then he steps into a meeting where the details of that plan are being dissected once again. Seated around a conference table are a group of current and former Columbine staff, students and law enforcement who have spent months organising the 20th-anniversary events – a week of service projects and ceremonies.

There will be a rally for current students, a public memorial service for thousands and a private open house for survivors who want to visit the building. Some who RSVP’d have not been inside the school since they ran out of it on 20 April 1999.

The week is a chance for the organisers to present Columbine as they see it: a community that came back stronger, focused not on its past but on its dedication to help others.

Those who lived through the attack went on to become doctors, nurses, counsellors and first responders. Five returned to Columbine to teach alongside 13 educators who remain from those days. Ireland, the student who crawled through the curved green windows, works as a financial adviser in nearby Lakewood. The students have each found their own ways to prove that their lives were about more than what two of their classmates had inflicted on them all those years ago.

But in recent months, they found themselves once again bombarded with calls from reporters who wanted them to revisit that day. Frank DeAngelis, who was principal at Columbine during the attack and for 15 years afterwards, had nearly 50 interviews to do in the month before anniversary events he was helping to plan.

The start of spring is always the most difficult part of the year for him. He says he’s been in six car accidents during the month of April since 1999. This year, he felt the distraction seeping in even earlier. But his support system is in place – faith, family, friends, a trusted counsellor whom he saw for therapy. He feels like he is handling it all well.

Then he went to a doctor for what he thought was a spider bite and learned he had shingles. “Are you under any stress?” the doctor had asked.

When the meeting is over, McDonald follows DeAngelis out. He depends on the former principal for insight into the community, on how he can balance security with sensitivity. But as they start to talk, one of McDonald’s officers appears.

“John, did you okay CNN being here?” he asks. “They’re in the parking lot.”

While McDonald is busy threatening the CNN crew with trespassing charges, the current principal of Columbine is in his office listening to a broadcast of the school baseball team’s first game of the season. Scott Christy’s days are spent leading meetings, talking with parents, observing classrooms, planning for prom – running Columbine, the school, a place filled with students who weren’t even born when the attack happened.

“Ninety-eight per cent of the time, maybe more – 99 per cent of the time, it’s just a school. We’re doing our best to prepare our kids for the future,” Christy says.

Then there are the times when Columbine the school becomes Columbine the symbol.

It happens after every new school shooting: the media calls, strange emails and outsider threats spike. After Parkland, there were 169 tips about school-shooting threats in two weeks. Christy, 42, tries to remain unfazed; he knows McDonald’s team will tell him when there is reason to worry. But that has been far harder in the past few months, since the threat Columbine received before Christmas.

On 13 December, schools, government buildings and newspapers across the country received emailed bomb threats from someone demanding payment in bitcoin. But the threats to Columbine came in the form of phone calls to 911 and to the school itself.

The callers claimed there was a bomb and someone with a gun in the school. Within a minute, McDonald’s team and the sheriff’s department were inside searching for them.

Christy was alerted immediately, but he wasn’t at the school. It was the rare day when he was at the district’s headquarters, 30 minutes away. He ran to his car and sped down the highway at 100 miles an hour. When he made it to Columbine, the school was surrounded by police cars blocking his way.

“I’m the principal,” he pleaded. The officers wouldn’t let him by. Christy flung his car door open and sprinted towards the school.

“We’ve got a runner!” McDonald heard someone say over the radio. When he realised what was happening, he ordered that Christy be let in. By then, McDonald was sure that the threat was a hoax. The callers’ timelines didn’t make sense. And the security cameras could instantly check the areas where they said the bombs were located. Students were kept locked inside the school, but teaching continued as usual.

Three months later, Christy was still finding it difficult to be away from the school, he confides to McDonald, who has stopped by his office after scolding CNN.

“I’m supposed to be out on Friday... and I’m dreading that,” Christy says. “I am responsible for this place. If something were to happen, I have to be here. To protect my school and my kids and my staff.”

“I share that anxiety,” McDonald replies. “My fear is not being here. Here or any other school. To me, that is what would be devastating.”

They have both thought about just sleeping at the school during the 19th and 20th. McDonald’s team have all been notified that every one of them should plan to work the whole weekend. But he still hasn’t settled on where to set up a command centre inside the school.

“You got time to show me that room?” McDonald asks.

“Yeah,” Christy says. “Let’s go do that.”

The room is large and windowless, with doors that lead to multiple hallways, the perfect spot for his people to do the work of keeping everyone safe without being seen.

“I’ll take it,” McDonald says, and as he makes his way to leave, he catches the signal going out on the radio on his hip. He picks it up.

“What’s happening?” he says.

“It is a Safe2Tell of a former student,” the dispatcher responds. McDonald guesses what is coming next.

“Is it a threat?”

The third threat of his day sounds different, worrisome. A 19-year-old former Jefferson County student has been brought into a hospital by his mother. He reportedly said he was in love with a current student, but two of her male friends are in his way. He was planning to “remove” them. The hospital placed him on a mental health hold and called the police.

Local law enforcement was already sending officers to the houses of the students involved. They were working to find out whether the 19-year-old had access to weapons. McDonald tells the dispatcher he wants one of his own officers stationed at the school that could be targeted. The mental health hold would buy them time; they just didn’t know how much.

“If he gets out tonight,” McDonald tells the dispatcher, “I don’t want to be surprised tomorrow.”

He drives straight back to his office. His threat-assessment team need to come up with a plan for keeping the 19-year-old monitored and the school secure. He needs to call in John Nicoletti, the psychologist he trusts to give an analysis of the teenager and his state of mind. He does everything he can to ensure that this young man receives every possible resource to keep him off the path to violence.

His phone rings again. The school system’s chief operating officer wants to be filled in.

“You think this is real?” his boss asks when he hears the details.

“Yeah,” McDonald says. “I think this is one we better be alerted to. Better be on guard for. For sure.”

He hangs up the phone. It is almost 7pm. He has been at work for 13 hours. Three threats. A fairly slow day, he thinks. Everything working as it should. Everyone safe.

He says goodnight to the dispatchers before driving home. He hears them talking on the radio all evening, while he puts away his Smith & Wesson, changes out of his uniform and waits for the local police to call with an update. He finally goes to sleep, one day closer to the anniversary.

The sound of his ringtone wakes him up at 2.13am. The sheriff’s department is calling. He listens to find out how bad this one is going to be.

A man and a woman have just been stopped in the Columbine parking lot. They want to take selfies next to the main entrance. They want, they say, to pay their respects.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments