Their children died in hot cars – now they’re fighting for legislation to stop it happening again

Since 1990, more than 900 children have died in the back of hot cars in the US. It's worse in summer, and climate change is exacerbating the problem. Chris Stevenson meets the grieving parents campaigning for new laws and new technology

Do you have a doll in the back of your car?” was the question that sparked the most visceral reaction Miles Harrison will likely ever experience. Harrison was coming to the end of a string of busy days involving a 700-mile round trip from his home in Virginia to Ohio to show his parents his new son, Chase, whom he and his wife Carol had just adopted from Russia. That morning, he’d dropped by the dry cleaners before heading to a hectic day at the office.

The question caused a wave of nausea to flow over Harrison and he gagged, realising what had happened, before running to his car. In the back was Chase, nearly two years old. The doting father, who had spent the past six weeks bonding with his new son after his arrival in the US, was meant to take Chase to daycare, but had forgotten to take the exit on the highway. He then parked his car and headed into work, believing whole-heartedly he had dropped his son off.

But here, around 5pm, was the evidence that he hadn’t. “I could see the outline of a baby in the back seat,” he says, “and I knew it was him.” The result was blind panic as Harrison “fell apart”. “I started screaming and I ripped him out of his car seat and rushed inside screaming incoherently,” he says, his voice quivering. “Someone eventually took him from my arms as I was just running around screaming ‘Oh God, not him, take me, take me’.”

As the police and an ambulance turned up at his office, Harrison tried to call his wife Carol, but she could not understand what he was trying to tell her as he was screaming down the line. She tried repeatedly to call him back. Later, at the hospital, a nurse came up to Harrison and offered him something for the pain – the father, who was in shock, said no.

“I said ‘no, I don’t deserve anything for the pain’,” Harrison recalls, adding: “I wanted to die, I begged God to take me.”

From the hospital, Harrison was taken to the police station. The first question officers asked was if he had a life insurance policy taken out against his son. Harrison didn’t, but was in no state to answer questions. “I was screaming unintelligible wails of despair and anger and shame,” he says.

That day – 8 July 2008 – and the weeks and months that followed are something that Harrison will forever be dealing with. The mitigating circumstances flow out not like a list of excuses but in clumps that show he is a man still struggling to understand how the tragic death came to pass. Chase was quiet in the back of the car, as adoptees often are at first – particularly if they don’t know the language. There was very little noise from the back of the car. He was in a cast thanks to a broken ankle and was tired.

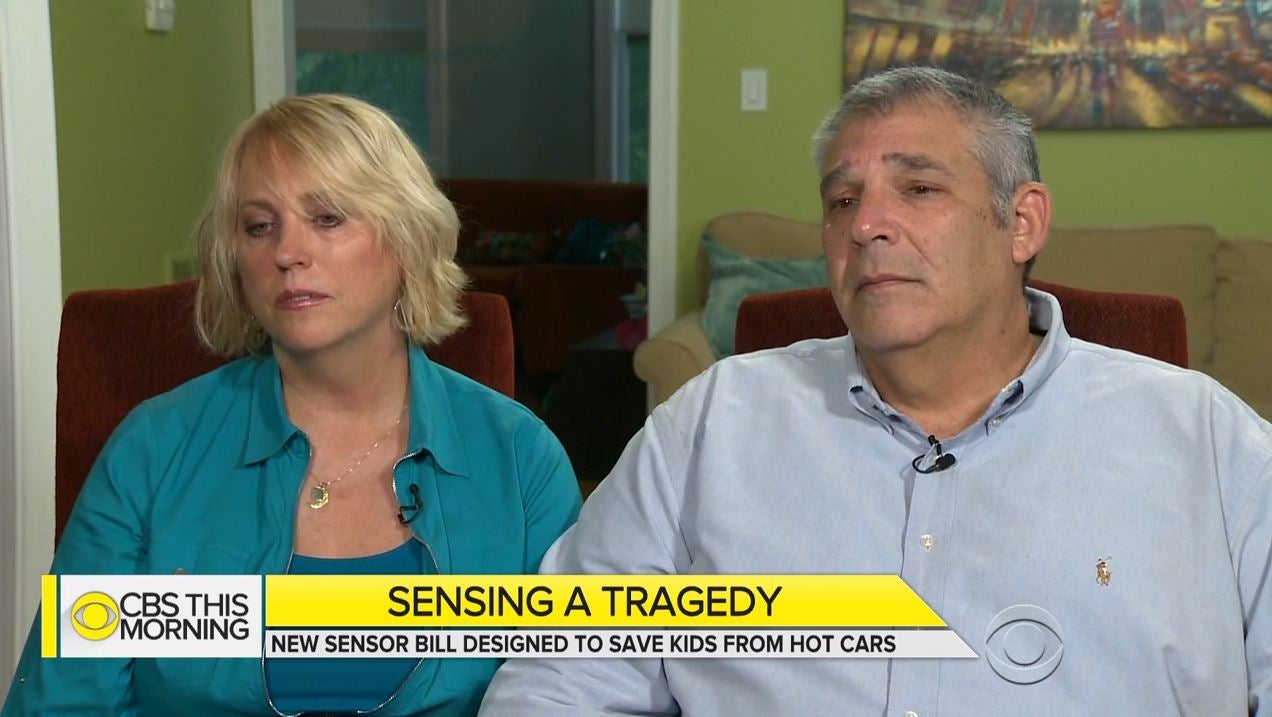

“This is something you can never explain away because there is no explanation for it,” says Harrison, who has faced the question hundreds of times over the years. “I have never forgiven myself,” he adds. “I am still so angry at myself over this. I live with this shame and guilt every day and don’t know when it will come to an end.”

Harrison, now 60 and still living with Carol and their eight-year-old daughter in Purcellville, Virginia, was charged with involuntary manslaughter over Chase’s death. After a three-day trial in Fairfax in December 2008, he was acquitted, but the ordeal was not over. In retaliation for US sanctions on Russian officials over the death of Sergei Magnitsky, a tax adviser who alleged corruption, Russia implemented a bill that involved banning US citizens from adopting Russian children. Still in effect today, the law was named after Dima Yakovlev, which was Chase’s name before he was adopted.

“It didn’t matter that I was found not guilty – I still feel guilty,” Harrison says. “I’m not looking for pity… I did this, I killed him. It wasn’t on purpose but I did do it.”

While this tragedy played out partially on the international stage, children dying in hot cars happens all too frequently in the US. In 2018, 52 children across the country died from heatstroke within a vehicle – that is a record. Since 1990, more than 900 children have died in such a way. And more than 50 per cent of them have been accidents where adults have left children in their car. In around a quarter of cases, children have let themselves into the car, and in about 20 per cent of cases an adult was found to have left the child deliberately.

This year at least 30 children have already died from heatstroke, with the summer months of July and August peak time for such tragedies to occur. Last week, Juan Rodriguez of New York left his near one-year-old twins in his vehicle for eight hours while at work. Facing a manslaughter charge, he is said to be in a state of disbelief, struggling to understand how he could have forgotten to drop them off at their daycare. His wife Marissa has called the tragedy a “horrific accident” and is standing by her husband.

“I assumed I had dropped them off at daycare before I went to work,” Rodriguez told police, according to court documents. “I blanked out. My babies are dead.”

On Wednesday night, a one-year-year boy was found dead in a car in Columbus, Nebraska, having been inside for more than eight hours. Police said the death was an accident with the mother having her routine disrupted which resulted in leaving the infant in the vehicle in her work's car park. In other recent cases, two-year-old Scarlett Grace Harris, who was found dead in the family car in San Diego, California, on Monday after her mother had taken a nap in the house, while 21-month-old Damian Elias Leyna who was pronounced dead at the hospital after being found unresponsive in his parent’s vehicle in Georgia having been inside for 30 to 45 minutes.

Also on Monday, in South Carolina, a murder investigation was opened over the death of Cristina Pangalangan, 13, who was left in a car for five hours. Local sheriff’s said Cristina was incapable of caring for herself and allege that the teenager’s mother and the mother’s boyfriend only checked on Cristina twice in that time.

Last week there were two cases on 1 August. In Garland, Texas, police said a nine-month-old girl was found dead in a vehicle at a car wash with the temperature outside at 36C. Texas has seen the most child heatstroke deaths since 1990 – more than 120. In Corbin, Kentucky, two-year-old Aubrey Rose reportedly made her way outside her home and climbed into her father’s car to play with the steering wheel. When her father woke up from a nap he realised she was missing and called the police. After a search Aubrey Rose was found unresponsive in the vehicle and was pronounced dead at a local hospital.

For Harrison and groups across the country, the battle now is making sure that incidents like this do not happen again.

It is almost 20 years since Tania San Miguel, then aged 24 and living in McAllen, Texas, found her 20-month-old daughter Miah in the back of her car. Her story has many similarities to Harrison’s. Her then five-year-old son had been at home ill in the morning, but wanted to go to school in the afternoon. San Miguel took him and decided to take Miah to the daycare centre down the street from her home at the same time, before heading to work.

“In my mind I dropped her off at daycare and went to work,” she says. “About an hour later I called my nanny and I was joking with her about missing my daughter and she said to me ‘how was she when you dropped her off?’ – and I realised I couldn’t remember how she was when I dropped her off. It hit me that I hadn’t.”

It was the end of summer, 24 August 1999. “Miah was in the car for 45 minutes to an hour but it was just hot enough that day in Texas…”

San Miguel and Harrison describe similar reactions: screaming for help and being in shock. Miah died in the ambulance. San Miguel’s son was taken into protective custody and she was charged with injuring a child. Facing 10 years to life in prison, when offered a plea deal San Miguel says that she took the “hard decision” to accept a reduction in the charge and four years probation. That meant no jail time.

“Those first few weeks were unbearable,” she says. “There are no words to describe going from being a parent of two and knowing only how to be a mother. I always wanted to be a mum.”

Like Harrison, San Miguel says she wanted to die. She told how she jumped into her daughter’s grave and that she wanted to end it as she “loves and loved those kids with every breath of me”.

Hot car deaths – the numbers

Statistics for the number of children dying in hot cars per year in the UK and across Europe is difficult to collate. The Independent contacted organisations including the NSPCC, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents and the NHS, which were all unable to help. A request for information from the Office for National Statistics was not returned.

The European Child Safety Alliance has some dated statistics from across Europe, but was unable to assist with statistics for the UK. The alliance says that between 2007 and 2009, there were 26 cases of heatstroke in France and Belgium, including seven fatalities. The Netherlands, Iceland and Hungary have also all reported fatal cases in recent years.

She cites a moment of divine inspiration when she was at her lowest which helped her get back on her feet and fight for custody of her son. “There was one moment where I was sitting in a room, listening to my own breathing and my own heartbeat and willing it to stop as I couldn’t live without my kids,” she says.

A judge eventually granted her custody, calling Miah’s death a “terrible accident”. San Miguel needed to get away and moved to live with her twin sister Melanie and her husband, before later settling in Gig Harbour in Washington. The stigma of the accident followed her for years. “It was so unheard of… it was just a hateful, horrible time. It’s still not common. It is a taboo subject, but it is understood a little bit more.

“There were people that wanted to charge me with murder. I was being called a baby killer,” she adds.

She recalls one incident where she went out for pancakes with some family, who wanted to make sure she got out and had some conversation. She smiled at something someone said and the next thing she knew, her lawyer was on the phone saying she shouldn’t be seen doing things like that while the case was still ongoing.

“I couldn’t get a moment without having to live my grief,” San Miguel says. Her court-mandated group therapy did not help, with San Miguel believing her tragedy set her apart. She felt she was the only one who had gone through this. In fact, an average of 38 children a year have died in hot cars in the US since 1998.

For 10 years she kept quiet, before deciding to tell her story as part of a sharing exercise at work. It was therapeutic and San Miguel finally researched similar tragedies. She has remarried, but has not had another child since Miah died. “I couldn’t do it,” she says, adding that it took her a long time to even hold someone else’s child.

Her research led San Miguel to KidsAndCars.org, an organisation that has been fighting for education on the topic for nearly two decades. The group campaigns for national legislation to combat the issue. San Miguel took up the cause.

* * *

Some of the most comprehensive tracking of child deaths in hot cars, and the source of many of the statistics in this piece, was started by meteorologist Jan Null in 2001. The death of a five-year-old in the San Francisco Bay Area from heatstroke in a car led to calls from the media to investigate how a vehicle could get that hot. Information wasn’t readily available, so Null started studying. His results were eventually published in the scientific journal Pediatrics in 2005.

That study found that when it is 22C outside, the temperature inside a car parked in the sun could climb to 47C in just 60 minutes. Using media reports and official statistics, Null found data going back to 1998 – in that time at least 827 children have died from heatstroke in hot cars.

Null says that while the number of deaths has “not fluctuated greatly” when plotted as a rolling five-year average, even as the US population has increased, the problem is not going away and that climate change could make things even worse. The data that Null, who is part of the Department of Meteorology and Climate Science at San Jose State University, has collated leaves him scared at times.

“We have more deaths in the hot months… but it can happen in any month,” he says, adding that the end of the week is the worst period statistically. “There is a real trend for forgotten children later on in the week – so I hate Fridays. I’m never surprised if I see one on a Friday.”

Advocates have tried numerous times to get national legislation passed, but the fact that many parents’ struggle to believe it could happen to them is hampering education efforts. David Diamond, a professor of psychology in Florida, has studied the topic for years and spoke to Rodriguez in the days since his arrest in New York.

Diamond’s research indicates that when people drive a familiar route to work, for example, they can slip into “autopilot”. That state, he told The New York Times, also suppresses the higher-order part of consciousness that allows people to remember they had made a plan. Stress and sleep deprivation can make such memory lapses more common.

Amber Rollins, director at KidsAndCars.org, says the “disconnect” between what people think and what could actually happen makes the use of technology a legal requirement. “We have been working on this issue for the past 20 years and awareness and education on this subject are at an all-time high,” she says. “Everybody knows about hot car deaths – but the disconnect is that people still believe it would never happen to them.”

KidsAndCars.org has data reaching back to 1990, with some cases even older, although it is likely that the more than 900 deaths since then are an underestimate of the true scale of the problem. The Hot Car Act has been introduced in the House of Representatives and there is a companion piece of legislation in the Senate. The House bill calls for a loud alarm if someone is in the back of the car, which the Senate bill does not.

An alarm warning drivers about occupants in the back seat could have saved hundreds of lives and would likely cut the yearly average of 38 child deaths in half. It may also have an effect on cases where parents deliberately decide to leave children in the back of a vehicle. But Rollins is hopeful that the bill will be successful, despite the deeply entrenched divisions between Republicans and Democrats, especially as the House bill has sponsors from both parties. The Senate bill is co-sponsored by three Democrats, including the party’s leader in the chamber, Chuck Schumer.

“We are really very hopeful that we can get it through this session,” she says. “But it is difficult to gauge the chances of it passing as we are in such an interesting time in American politics at the moment and it is kind of unpredictable.”

Car manufacturers have claimed that the legislation will bring up costs and not fix the issue, as less than 13 per cent of new car buyers each year have a child under six. More than half of child deaths in hot cars are infants under two years old. Harrison and San Miguel have spoken to members of Congress, with San Miguel set to return to Washington DC in September to meet with more politicians as “the technology protects you whether you think it could happen to you or not”.

Harrison says the issue has been raised in other ways – including allowing documentary-maker Susan Morgan Cooper to interview him and his wife Carol about the case and the Russian political element. He credits Morgan Cooper and the film To the Moon and Back with saving his life and helping his marriage as the interviews allowed them to speak about Chase’s death together in a way the couple hadn’t before. Morgan Cooper is currently making a second film specifically on the tragedy of Chase’s death.

Harrison says that the technology works. When he bought a new car a few months ago, his daughter climbed into the back seat and when the salesman walked away with the keys the car made an almighty honking noise. The manufacturer had voluntarily added the alert. The noise made Harrison cry, and he took the car. “No question it would have saved my son’s life,” he says. “I am shocked we can’t get something passed in Congress.”

“I hate talking about it as it makes me relive it – but this is so important,” Harrison says. “And I am hoping I’m alive when there is some kind of a law that mandates an alarm system.”

For Rollins, the bill is about ending a fixable problem. “It is so frustrating as we know there is technology that exists that could have stopped those children from dying. And it is even more frustrating to think that there are parents out there holding their beautiful babies right now that aren’t going to have them by the time the summer is over.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments