Desperately seeking self-improvement: Two professors in pursuit of perfection became their own lab rats

Like a couple of lab rats, professors Cederstrom and Spicer have subjected themselves to every conceivable test in pursuit of perfection, hoping to become better human beings, smarter, more productive, more loveable. Andy Martin finds out if they succeeded

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Professor Carl Cederström looked in good shape. He had been in training for a weight-lifting contest. But right now he was pumping up his memory. And he had been memorising the long, exclusively male list of American presidents. At this particular moment in a café in West Village, New York, he asked me who came after Ulysses S Grant. I confessed I had no idea.

He then went on to explain how it was that he could remember that Ashgabat is the capital of Turkmenistan. When I left him he was trying to memorise the whole of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal. In the original French, naturally. Maybe it should be… the Odyssey?” I don’t know if he was talking about the Ancient Greek original or not.

Carl Cederström is co-author, with André Spicer (a New Zealander and professor of organisational behaviour at the Cass Business School in London), of Desperately Seeking Self-Improvement, a book the like of which has never been done before – and almost certainly will never be done again – in which two white-coated professors use themselves as their own lab rats to work out if our obsession with self-improvement has any verifiable results.

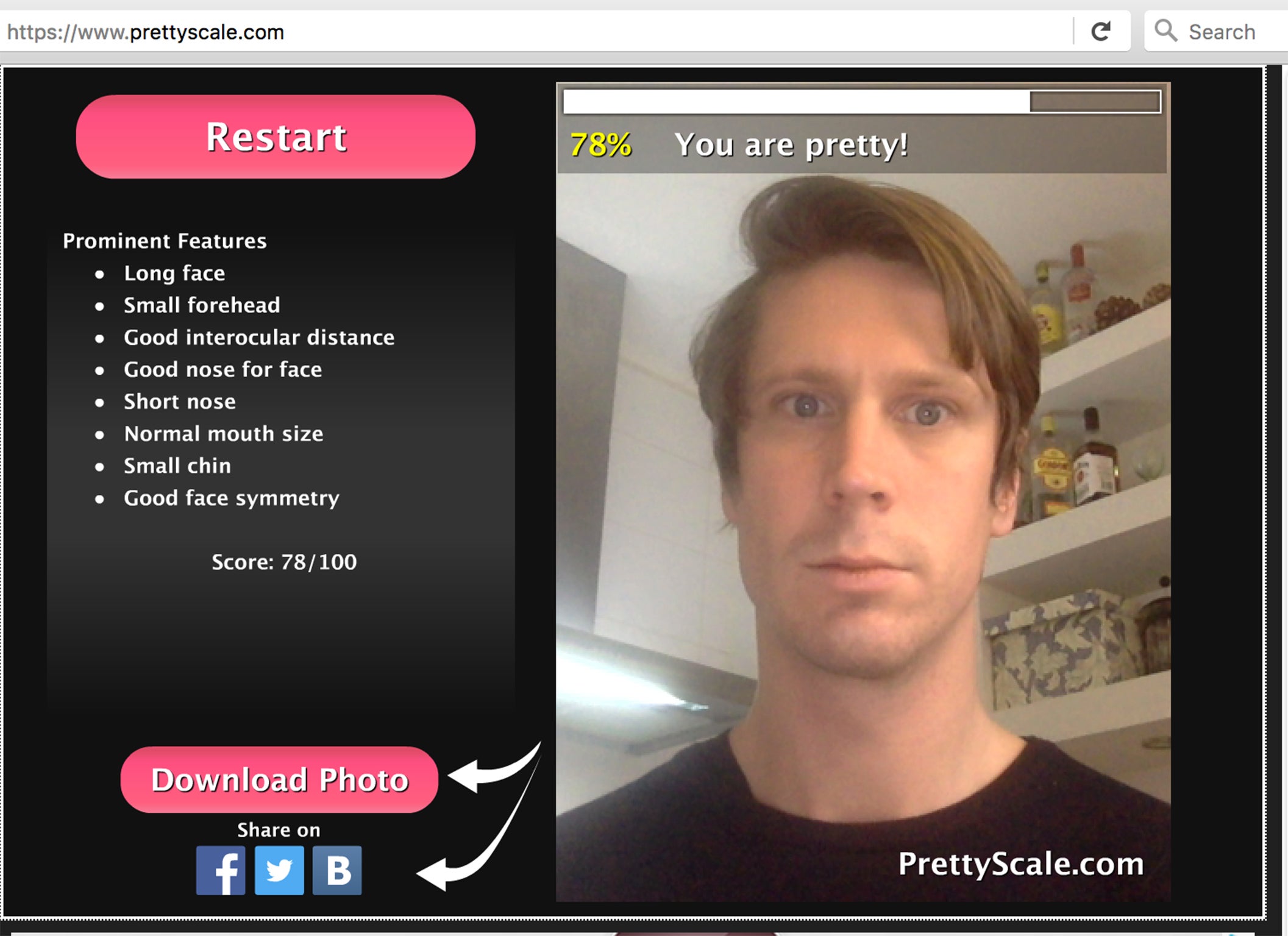

In alternating diary entries, over 12 months, intrepid explorers of the outer limits of self-optimisation, they try out drugs, new technology, physical and mental training, and assorted sex accessories. With a view to re-engineering themselves into better human beings, smarter, more productive, more loveable – to becoming more like gods (especially when wearing the “God helmet”) – and nearly killed themselves and their own friendship doing it.

They approached the whole contemporary Kama Sutra of different techniques in a spirit of scepticism, satirists as much as social scientists, but they get swung around and seduced by a few things along the way.

There is a grand tradition of self-help manuals, going back to Think and Grow Rich and the classic, How to Win Friends and Influence People. Alain de Botton’s How Proust Can Change Your Life is part of the canon too. Now these amiable exercises in positive thinking have swollen to become a vast, bloated, and terrifying industry, from cosmetic surgery through to “brain hacking”.

Cederström and Spicer were intent on testing out everything to the maximum, to the point of self-destruction, madness, and melancholia. All self-improvement exacts a toll. Even upping the amount of pleasure in your life involves a measurable increase in punishment and pain. The chapter on “sex” demonstrates the point. This is like Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me applied to the erotic realm, with extra orgasms in place of cheese.

Cederström, who is tall and gangly, bulked up to have a shot at a strongman contest. He had to eat breakfast for four people and wash it all down with a protein shake.

Spicer trained up in a few weeks to run a marathon. Together they try out every quick-fix fantasy under the sun. And several religions (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism). Not to mention the wisdom of Ekhart Tolle (The Power of Now). They wear magnets and magic watches and give themselves electric-shock treatment. They chant Hare Krishna (which has a positive and calming effect, oddly enough). They climb mountains (literally). They chain smoke, stuff themselves with burgers in the name of hedonism, and they go vegan and drink nothing but water and cleanse themselves rigorously.

They subject themselves to serial oppressive apps that keep tabs on their calorie intake and every waking moment (and sleeping too). The masturbation devices, in particular, run into an insuperable problem: as Cederström puts it: “I could think of many people I wouldn’t like to have sex with, and I was one of them.” They also have a shot at doing nothing (which turns out to be ridiculously difficult).

Among their major achievements: Cedertröm speed-reads Proust’s In Search of Lost Time and memorises pi to 1000 decimal places. He also speed-writes a nordic noir novel. And he learns French in less than a month, well enough to be able to participate in a radio show (again, the drugs probably helped, but it was still one of the most searing experiences of his life). Spicer turns himself (briefly) into a stand-up comic (despite not having a funny bone in his body).

Neither author is really a believer. They heaped derision on the culture of happiness in their earlier work,The Wellness Syndrome. They demand the basic human right to be miserable. They are similarly agnostic where the religion of self-improvement is concerned. As Spicer says, “The only difference seemed to be that while the Bible asked you to have faith in God, most self-help books asked you to have faith in yourself.” But they develop greater tolerance and understanding. “I was less cynical now than before,” writes Cederström. “Going to the new-age retreat had exposed me to the suffering and pain of these people. They felt lonely and sad. Some were dying. There was nothing ridiculous about them. All they wanted was for their lives to be a little bit better, a little less painful.”

The task of self-improvement is inevitable, endless, but also doomed to disappointment. No wonder Cederstrom and Spicer fall out. “When he suggested he should run a marathon,” says Cederström, “I said he should run an Ironman. Whatever he suggested, I always thought it was not enough. I said he could do more and better.”

Ultimately nothing less than omniscience and omnipotence is acceptable. Immortality would be nice too. But, as Keynes pointed out, in the long-run we’re all dead. Maybe, at the expense of considerable effort, you can hold back the tide for a while. Cederström and Spicer lived to tell the tale. There are no visible scars. At the end of it they have conjured up a unique book, described by Steven Poole in the Guardian as “an absurdist masterpiece”. Now they are in New York to talk about their experiences. So maybe some of these techniques really work. Contrary to their original intentions, they might actually encourage people to try out some of them.

Consider the so-called “Pomodoro”, for example. When I went to see Cederström in his native Stockholm, where he teaches at the University of Stockholm Business School, he sat me down and got me to work for most of a day in stints of 25 minutes on and 5 minutes off, total concentration followed by random down-time and coffee-making, religiously observed (you can’t keep going beyond the 25 and you have to crack on after 5, without fail). It’s like having a slave driver on your back. But the fact is it works. We were both ridiculously productive. Whether any of it was any good is another matter which only the gods can determine.

On the purely physical side, I am also quite taken with the Tabata. Discovered in the 1990s by Japanese scientist Izumi Tabata, this involves short high-intensity bursts of activity: 20 seconds on (really on – pedal-to-the-metal, uncompromising cardio-mania), 10 seconds off, repeated 8 times. The first time you try it, you think you’re going to die. Maybe the second time too. I hear that the author James Salter died aged 90 in a gym. They found him on the Stairmaster, dead as a dodo. It’s not such a bad way to go.

Desperately Seeking Self-Improvement, through sheer fervour, fanaticism and over-exertion, is up there, in terms of quasi-religious dedication to an absurd cause, with The Year of Living Biblically, by AJ Jacobs. Philosophically, Carl Cederström and André Spicer finally converge on the sentiments expressed by Mark Manson in his book, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck. More than anything, in their repeated bursts (almost like a pomodoro) of insane hope followed by despair, they remind me of the manic-depressive dialogue of Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot: “We are happy. (Silence.) What do we do, now that we’re happy?”

http://www.orbooks.com/catalog/desperately-seeking-self-improvement

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments