Can the cruelty of San Fermin’s legendary bull-running festival be ignored any longer?

With Pamplona’s controversial and bloody festivities in full swing, David Barnett explores the fascinating, yet troubling, nature of this annual event

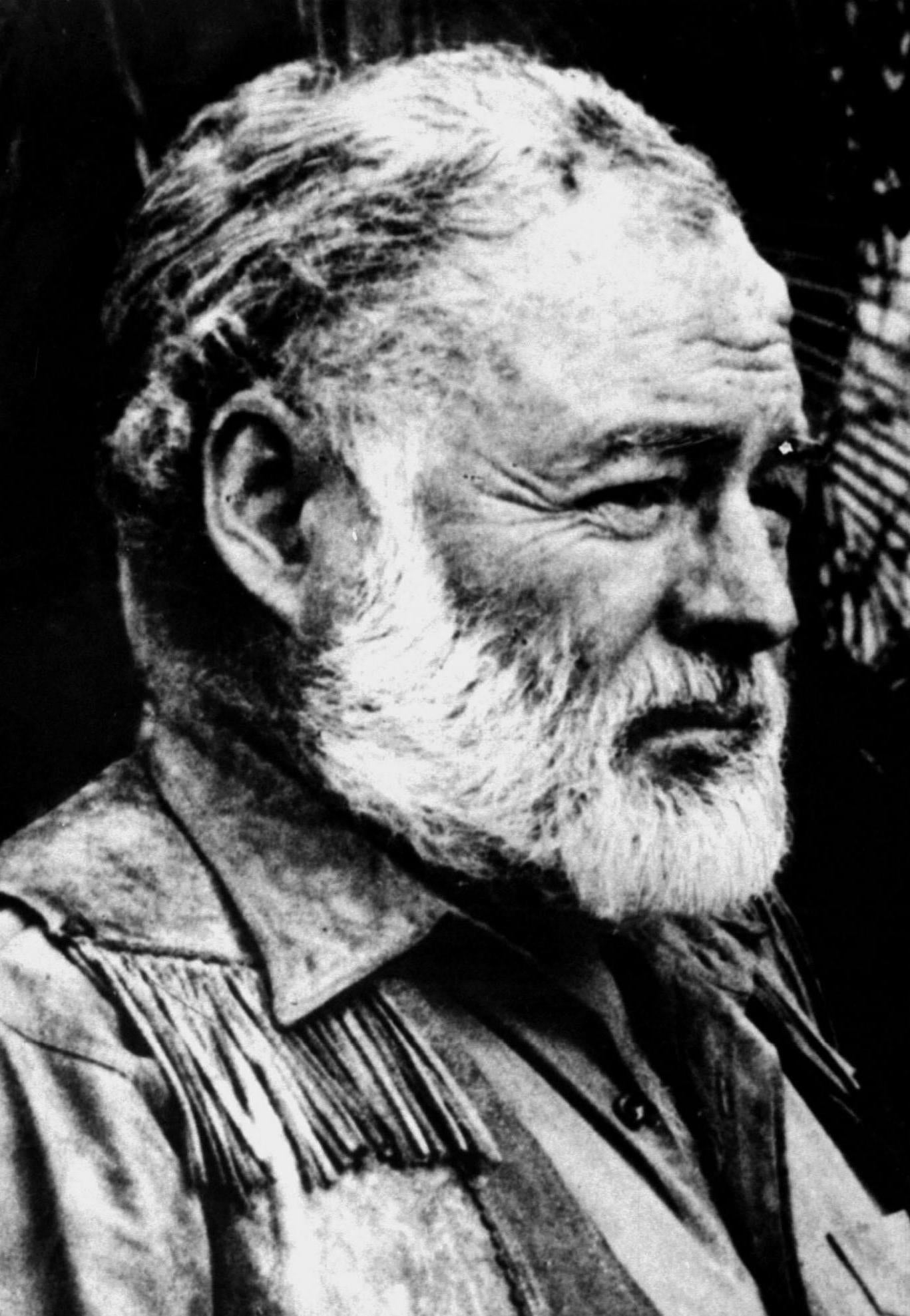

It was, said Ernest Hemingway in a letter to his old friend Howie Jenkins, “the goddamdest wild time and fun you ever saw. Everybody in town lit for a week, bulls racing loose through the streets every morning, dancing and fireworks all night.”

Hemingway wrote that just about 95 years ago, upon witnessing his very first festival of San Fermin in the mountain town of Pamplona, in the heart of Spain’s Basque region. San Fermin starts every year on 6 July and runs until the 14th of the month, and the spirit of Hemingway’s breathless description of 1924 pretty much still holds today.

San Fermin is many things. It is a religious festival, in honour of the titular saint who is said to have been the son of a Roman senator who converted to Christianity in the third century. It is one long party, that draws people from across the globe for a week of drunken debauchery. It is a spectacle of parades featuring gigantic puppets with grotesquely oversized heads. But for most people, Pamplona and San Fermin means just one thing: the running of the bulls.

Many places in Spain have bullfights and many towns host bull runs, in which the streets are barricaded off to allow the animals to thunder along an enclosed route, usually with the brave and foolhardy running alongside them. But there are none as famous as Pamplona’s.

And that’s largely thanks to Hemingway. A statue of him stands outside the Pamplona bull ring, often garlanded with the ubiquitous red neckerchiefs that form the uniform of those who partake in the bull run, along with white shirts and trousers and a red sash around the waist. Hemingway, after ending up in Pamplona with his friends in the Twenties, became enamoured by the bull run and the bullfights that followed, returning most years until the late 1950s.

Hemingway got a lot of mileage out of Pamplona, and his exploits became inflated into the stuff of legend, with various unsubstantiated and largely apocryphal stories that he had been variously tossed, gored and trampled by the Pamplona bulls. For years after his first visit the tales would grow in the telling, fixing Hemingway’s reputation with the public as a two-fisted hero not only of the First World War that informed his work, but of the adventure and derring-do he began to draw on for his later novels.

The author repaid the notoriety Pamplona gave him by making the city, and San Fermin, central to his novel Fiesta, or The Sun Also Rises, which accounts for his fame in the town and the statue that honours him. The novel, published in 1927, acted as a guide book and tourist brochure for Pamplona, driving adventurous young Americans there in Hemingway’s footsteps, and then providing the impetus for thrill-seekers from across the world to do the same in the subsequent decades.

That’s certainly true for Andy Smart, who this week will take on his 62nd Pamplona bull run. Smart is a veteran of the 1980s stand-up comedy scene and the Edinburgh Fringe; he was a member of the Comedy Store Players improvisation group with Paul Merton, and – with Angelo Abela – formed the Vicious Boys, appearing on the likes of The Tube TV show. He still performs improv at the Comedy Store and is a guest presenter on TalkSport radio, expounding on football. He has also done the Pamplona bull run every year since 1982.

That year he had left his native Liverpool to head to Spain for the World Cup. England were playing France on 16 June, his 23rd birthday. England won the game 3-1 in Bilbao, but Smart didn’t have any plans after that so he “followed a bunch of Swedes to Biarritz”. On the journey he was reading Hemingway’s novel for the first time. He says: “I was at a bit of a loose end so I decided to head to Pamplona to see what it was all about.”

What it is all about is this: between Santo Domingo Street and the city’s bullring, the side-streets and alleys are blocked off with wooden barricades, creating a single route that is mainly uphill and covers 875m. From around 6.30am, the runners file into the square at Santo Domingo. Here is a corral where the bulls are held. They are different bulls every day (for reasons which soon become apparent), usually all from the same ranch or breeder on any given day.

At 8am the crowd chants a prayer that roughly translates as: “We beseech San Fermin to guide us in this run and to give us his blessing.” Then a rocket is fired into the bright, blue morning sky. This means that the bulls have been released. It is wise, at this point, to start running. There is no way that anyone can start at Santo Domingo and run the entire course ahead of the bulls. There are simply too many people and the bulls are just too fast. At some point, unless you ease yourself well along the course before the rockets go off (the second firework indicates that all six of the morning’s bulls have left the paddock and are on the streets), you will be passed by the bulls. If you are lucky, they won’t stop to try to gore you.

You get stag parties turning up to take part, not really knowing what’s going on. These are not like cows you see chewing grass in the fields at home – these bulls have wide horns and they’re fast

Eventually, the runners and bulls enter the large bullring, where spectators gather and cheer them in. The bulls run into a corral, and are released in ones and twos, to chase the runners around the ring. Then the run is declared over, and the festivities – generally revolving around drinking – begin again in earnest. “I’d not really heard of the bull run before I arrived in Pamplona for the first time,” says Smart. “Obviously, this was well before the internet and it never really made the international news, unless someone was gored.”

So, in blissful ignorance, he did it. And he was hooked. And he vowed to go back the next year, and the next, and now, having just turned 60, he’s there again. After so many runs, he’s surely an old hand at it now?

“Actually, the more you do it, the more scary it gets,” he says. “And that’s because you know what can go wrong. When you first do it you’re sort of fearless, but that’s because you haven’t really seen the really nasty stuff that happens.”

By that he means the fact that if you fall over during the run, the bulls can stampede over you. And they often do. Their horns are vicious and they can gore runners. Which they often do. With their powerful heads they can toss grown adults up and over, and into the path of more bulls behind. Which they do.

Since they started keeping records of such things, in 1910, there have been 16 fatalities at the San Fermin bull run. Of those 16, all but two were Spanish. The most recent death was a decade ago in 2009, when Daniel Jimeno Romero was gored on the fourth day of the festival. Perhaps the most notorious death is that of Matthew Peter Tassio, who perhaps received more international media attention in 1995 because he was American. The 22-year-old from Illinois was felled by one bull, one of the smaller steers that run along with the main herd. He got up, but was in the path of one of the far more dangerous fighting bulls. He was gored straight through his stomach, the horn puncturing his kidney and severing a major artery. He was tossed 23 feet into the air.

Tassio’s death perhaps highlights a growing issue with the bull run, in that many people are taking part without fully understanding the dangers, nor knowing what to do if they get into trouble. The key piece of advice everyone is given is that if you fall down, stay down, which Tassio didn’t. Standing up again is going to attract more attention from the animals. Covering your head and rolling into the gutters might get you some bruising, but you’re more likely to come out of it alive.

Smart says: “I see a lot of people taking part these days who haven’t even taken a quick look at the advice. You get stag parties turning up to take part, not really knowing what’s going on. These are not like cows you see chewing grass in the fields at home. These bulls have wide horns and they’re fast.”

When Smart first started doing the run, there were around 1,500 people doing it each day. Now, he says, it’s more like 4,000. He’s been hospitalised twice; once a bull charged him but its wide horns went either side of his body. Unable to gore him, it ran for some 25 yards with him clinging to its horns, then tossed him 12 ft into the air. He escaped with three cracked ribs.

Another time he was knocked out cold, and awoke in hospital. The Pamplona authorities are extremely indulgent of the runners, and arrange for quick, efficient hospital treatment for anyone injured. And it’s all free, says Smart, so long as you’re happy to give a thumbs up to the photographer from the local paper to show there’s no hard feelings.

The bull-run is only the start of the day for the animals, and it generally ends in death after they take part in traditional bullfights in the Plaza de Toros – but with most parts of Spain turning their backs on bullfighting, it’s something that cannot be ignored in 2019

This year’s San Fermin festival got going on Sunday. On the first day of the run, 48 people required medical treatment, including a 46-year-old American who was gored in the neck. On Monday, the second day of the running, five people were injured. Despite all this, Smart says: “When you’ve done it once, you just have to keep doing it again.”

I tell him that I am the exception that probably proves his rule. I did the run in 1991, aged 21, filled with youth and bravado and fearlessness and last night’s beers. It was the most terrifying experience of my life. It made me feel so alive I could almost taste the crackle of electricity on the warm air when we ran into the bull-ring. I can see how that would become almost addictive, but it wasn’t really an experience I was in a huge rush to repeat.

Smart has detailed his bull runs, along with his other adventures in Europe, in a book that’s out on 25 July, A Hitch In Time (AA Publishing), and he recalls the celebrities he’s seen in Pamplona for the run. The 1991 movie City Slickers started with Billy Crystal and his thrill-seeking pals doing the bull run, which was filmed on location during San Fermin. Smart was one of a crowd of revellers gathered together to run up and down the streets for the cameras to simulate the run, and when Smart saw it on film he recalls it was “nothing like reality”.

Another time he saw Michael Palin, filming his 1999 series Hemingway Adventure. Smart asked him if he was doing the run and Palin looked aghast and said: “I’m not stupid, you know.”

So, we should probably talk about the bulls. They are the undisputed stars of the show. However, no matter how loud the applause when they run into the ring at the end of the course (which, incidentally, takes around two-and-a-half minutes to complete), they don’t exactly get a heroes’ welcome.

The bull run is only the start of the day for the animals, and it generally ends in death. They take part in traditional bullfights in the Plaza de Toros. Many of those who attend the bull run don’t go on to watch this – myself included – but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to ignore and it understandably attracts widespread condemnation. I confess I barely gave this aspect of San Fermin a second thought back in 1991, but with even many traditional parts of Spain turning their backs on bullfighting, it’s something that cannot be ignored in 2019.

Many campaign groups fight against the glorification of the death of bulls at San Fermin, and there is even an annual naked run along the route by protesters. Peta (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) calls the bull run, as a precursor to the evening’s bullfights, nothing more than a “death march”. It says: “Each morning, a rocket is launched to terrify six bulls – who are naturally high-strung and skittish – so that they’ll charge on to city streets lined by screaming tourists, who frequently hit them as they pass. The panicked animals slip and slide down the narrow streets and often smash into walls, sustaining broken bones and other injuries.

And that’s before the evening’s bullfights start. Peta adds: “Every evening, one by one, the bulls are forced into the bullring. Each bull first faces the picadors (men on horses), who jab him with a lance. It’s thrust into his back and neck muscles, then twisted and driven deeper to ensure significant blood loss.

“Next, banderilleros (men with brightly coloured harpoons) plunge their weapons into the bull’s back, causing intense pain. They make him run in circles until, dizzy, disoriented, exhausted, and weak from blood loss, he gives up.

“Finally, the matador (which means “killer” in Spanish) enters and attempts to kill the bull by stabbing him in the back with a long sword, aiming at his aorta or lungs. If that doesn’t kill him, the matador uses other weapons, including daggers, to cut his spinal cord. Bulls are often left paralysed but still conscious as their ears and tail are cut off and presented to the matador as trophies. As the bull draws his last breath, he’s chained by the horns and dragged out of the arena.”

And the bulls’ journey doesn’t quite end there. I have a vague, uncertain memory of someone selling bull stew late at night after the bullfights. Smart doesn’t think that’s right, but says that a Pamplona butcher does sell cuts of meat every morning from the bulls that have been killed the previous night.

I expect him to be fiercely supportive of the bull run, given he’s been doing it since 1982, but he’s somewhat more philosophical than that. He says: “I don’t think it will be that long before it’s banned. So many places in Spain have stopped bullfights altogether, areas like the Basque region are the last ones to keep it going. But while San Fermin is still going, I’ll be there for as long as I can, just for the adrenaline rush.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks