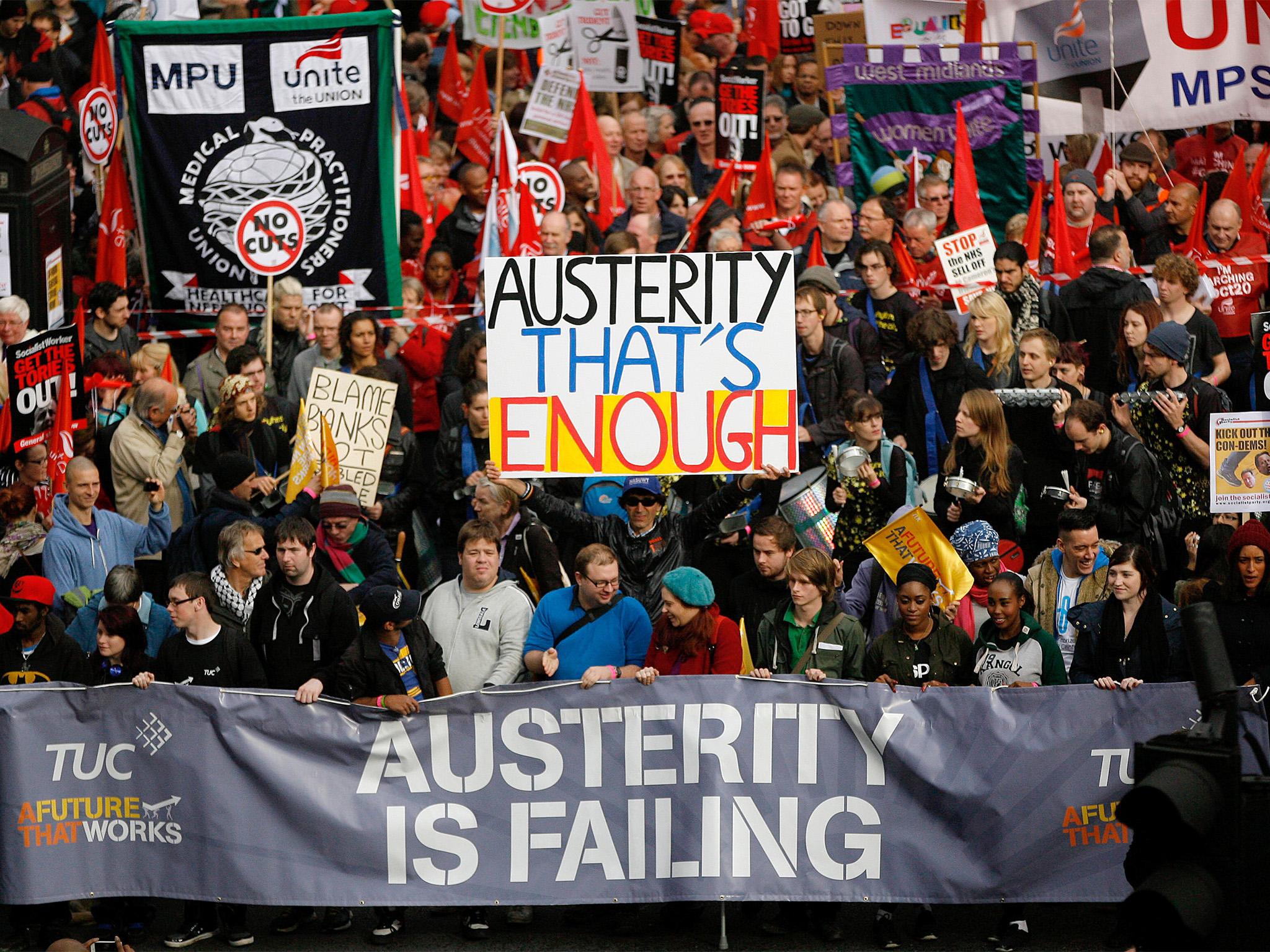

The big squeeze: In slow-bleed Britain, austerity is changing everything

After eight years of budget cutting, too many communities are looking less like the rest of Europe and more like the United States, with a shrinking welfare state and spreading poverty

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A walk through the modest town of Prescot in the Northwest of England amounts to a tour of the casualties of Britain’s age of austerity.

The old library building has been sold and refashioned into a glass-fronted luxury home. The leisure centre has been razed, eliminating the public swimming pool. The local museum has receded into town history. The police station has been shuttered.

Now, as the local government desperately seeks to turn assets into cash, Browns Field, a lush park in the centre of town, may be doomed, too. At a meeting in November, the council included it on a list of 17 parks to sell to developers.

“Everybody uses this park,” says Jackie Lewis, who raised two children in a red brick house a block away. “This is probably our last piece of community space. It’s been one after the other. You just end up despondent.”

In the eight years since London began sharply curtailing support for local governments, the borough of Knowsley, a bedroom community of Liverpool, has seen its budget cut roughly in half. Liverpool itself has suffered a near two-thirds cut in funding from the national government – its largest source of discretionary revenue. Communities in much of Britain have seen similar losses.

For a nation with a storied history of public largesse, the protracted campaign of budget cutting, started in 2010 by the coalition government led by the Conservatives, has delivered a monumental shift in British life. A wave of austerity has yielded a country that has grown accustomed to living with less, even as many measures of social wellbeing – crime rates, opioid addiction, infant mortality, childhood poverty and homelessness – point to a deteriorating quality of life.

When Lewis and her husband bought their home a quarter of a century ago, Prescot had a comforting village feel. Now, core government relief programmes are being cut and public facilities eliminated, adding pressure to public services like police and fire departments, just as they, too, grapple with diminished funding.

By 2020, reductions already set in motion will produce cuts to British social welfare programmes exceeding $36bn (£27bn) a year compared with a decade earlier, or more than $900 annually for every working age person in the country, according to a report from the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University. In Liverpool, the losses will reach $1,200 a year per working-age person, the study says.

“The government has created destitution,” says Barry Kushner, a Labour councillor in Liverpool and the cabinet member for children’s services. “Austerity has had nothing to do with economics. It was about getting out from under welfare. It’s about politics abandoning vulnerable people.”

Conservative leaders say that austerity has been driven by nothing more grandiose than arithmetic.

“It’s the ideology of two plus two equals four,” says Daniel Finkelstein, a Conservative member of the House of Lords, and a columnist for The Times. “It wasn’t driven by a desire to reduce spending on public services. It was driven by the fact that we had a vast deficit problem, and the debt was going to keep growing.”

Whatever the operative thinking, austerity’s manifestations are palpable and omnipresent. It has refashioned British society, making it less like the rest of Western Europe, with its generous social safety nets and egalitarian ethos, and more like the United States, where millions lack health care and job loss can set off a precipitous plunge in fortunes.

Much as the United States took the Great Depression of the 1930s as impetus to construct a national pension system while eventually delivering health care for the elderly and the poor, Britain reacted to the trauma of the Second World War by forging its own welfare state. The United States has steadily reduced benefits since the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s. Britain rolled back its programmes in the same era, under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher. Still, its safety net remained robust by world standards.

Then came the global financial panic of 2008 – the most crippling economic downturn since the Great Depression. Britain’s turn from its welfare state in the face of yawning budget deficits is a conspicuous indicator that the world has been refashioned by the crisis.

As the global economy now negotiates a wrenching transition – with itinerant jobs replacing full-time positions and robots substituting for human labour – Britain’s experience provokes doubts about the durability of the traditional welfare model. As Western-style capitalism confronts profound questions about economic justice, vulnerable people appear to be growing more so.

Conservative leaders initially sold budget cuts as a virtue, ushering in what they called the Big Society. Diminish the role of a bloated government bureaucracy, they contended, and grassroots organisations, charities and private companies would step to the fore, reviving communities and delivering public services more efficiently.

To a degree, a spirit of voluntarism materialised. At public libraries, volunteers now outnumber paid staff. In struggling communities, residents have formed food banks while distributing hand-me-down school uniforms. But to many in Britain, this is akin to setting your house on fire and then revelling in the community spirit as neighbours come running to help extinguish the blaze.

Most view the Big Society as another piece of political sloganeering – long since ditched by the Conservatives – that served as justification for an austerity programme that has advanced the refashioning unleashed in the 1980s by Thatcher.

“We are making cuts that I think Margaret Thatcher, back in the 1980s, could only have dreamt of,” Greg Barker said in a speech in 2011, when he was a Conservative MP.

A backlash ensued, with public recognition that budget cuts came with tax relief for corporations, and that the extensive ranks of the wealthy were little disturbed.

Britain has not endured austerity to the same degree as Greece, where cutbacks were swift and draconian. Instead, British austerity has been a slow bleed, though the cumulative toll has been substantial.

Local governments have suffered a roughly 20 per cent plunge in revenue since 2010, after adding taxes they collect, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies in London.

Nationally, spending on police forces has dropped 17 per cent since 2010, while the number of police officers has dropped 14 per cent, according to an analysis by the Institute for Government. Spending on road maintenance has shrunk by over a quarter, while support for libraries has fallen nearly a third.

The national court system has eliminated nearly a third of its staff. Spending on prisons has plunged more than 20 per cent, with violent assaults on prison guards more than doubling. The number of elderly people receiving government-furnished care that enables them to remain in their homes has fallen by roughly a quarter.

In an alternate reality, this nasty stretch of history might now be ending. Austerity measures were imposed in the name of eliminating budget deficits, and last year Britain finally produced a modest budget surplus.

But the reality at hand is dominated by worries that Brexit – Britain’s pending departure from the European Union – will depress growth for years to come. Though every major economy on the planet has been expanding lately, Britain’s barely grew during the first three months of 2018. The unemployment rate sits just above 4 per cent – its lowest level since 1975 – yet most wages remain lower than a decade ago, after accounting for rising prices.

In the blue-collar reaches of northern England, in places like Liverpool, modern history tends to be told in the cadence of lamentation, as the story of one indignity after another. In these communities, Thatcher’s name is an epithet, and austerity is the latest villain: London bankers concocted a financial crisis, multiplying their wealth through reckless gambling; then London politicians used budget deficits as an excuse to cut spending on the poor while handing tax cuts to corporations. Robin Hood, reversed.

“It’s clearly an attack on our class,” says Dave Kelly, a retired bricklayer in the town of Kirkby, on the outskirts of Liverpool, where many factories sit empty, broken monuments to another age. “It’s an attack on who we are. The whole fabric of society is breaking down.”

Austerity’s ‘knock-on effects’

As much as any city, Liverpool has seen sweeping changes in its economic fortunes.

In the 17th century, the city enriched itself on human misery. Local shipping companies sent vessels to West Africa, transporting slaves to the American colonies and returning bearing the fruits of bondage – cotton and tobacco, principally.

The cotton fed the mills of Manchester nearby, yielding textiles destined for multiple continents. By the late 19th century, Liverpool’s port had become the gateway to the British Empire, its status underscored by the shipping company headquarters lining the River Mersey.

By the next century – through the Great Depression and the German bombardment of the Second World War – Liverpool had descended into seemingly terminal decline. Its hard luck, blue-collar station was central to the identity of its most famous export, the Beatles, whose star power seemed enhanced by the fact such talent could emerge from such a place.

Today, more than a quarter of Liverpool’s roughly 460,000 residents are officially poor, making austerity traumatic: public institutions charged with aiding vulnerable people are themselves straining from cutbacks.

Over the past eight years, the Merseyside Fire and Rescue Service, which serves greater Liverpool, has closed five fire stations while cutting the force to 620 firefighters from about 1,000.

“I’ve had to preside over the systematic dismantling of the system,” says the fire chief, Dan Stephens.

His department recently analysed the 83 deaths that occurred in accidental house fires from 2007 to 2017. The majority of the victims – 51 people – lived alone and were alone at the time of the deadly fire. Nineteen of those 51 were in need of some form of home care.

The loss of home care – a casualty of austerity – has meant that more older people are being left alone unattended.

Virtually every public agency now struggles to do more with less while attending to additional problems once handled by some other outfit whose budget is also in tatters.

Stephens said people losing cash benefits are falling behind on their electric bills and losing service, resorting to candles for light – a major fire risk.

The city has cut mental health services, so fewer staff members are visiting people prone to hoarding newspapers, for instance, leaving veritable bonfires piling up behind doors, unseen.

“There are knock-on effects all the way through the system,” says Stephens, who recently announced plans to resign and move to Australia.

The National Health Service has supposedly been spared from budget cuts. But spending has been frozen in many areas, resulting in cuts per patient. At public hospitals, people have grown resigned to waiting for hours for emergency care, and weeks for referrals to specialists.

“I think the government wants to run it down so the whole thing crumbles and they don’t have to worry about it anymore,” says Kenneth Buckle, a retired postal worker who has been waiting three months for a referral for a double knee replacement. “Everything takes forever now.”

At Fulwood Green Medical centre in Liverpool, Dr Simon Bowers, a general practitioner, points to austerity as an aggravating factor in the flow of stress-related maladies he encounters – high blood pressure, heart problems, sleeplessness, anxiety.

He argues that the cuts, and the deterioration of the NHS, represent a renouncement of Britain’s historical debts. He rattles off the lowlights – the slave trade, colonial barbarity.

“We as a country said, ‘We have been cruel. Let’s be nice now and look after everyone’,” Bowers says. “The NHS has everyone’s back. It doesn’t matter how rich or poor you are. It’s written into the psyche of this country.”

“Austerity isn’t a necessity,” he continued. “It’s a political choice, to move Britain in a different way. I can’t see a rationale beyond further enriching the rich while making the lives of the poor more miserable.”

‘Prosperity for all’

Wealthy Britons remain among the world’s most comfortable people, enjoying lavish homes, private medical care, top-notch schools and restaurants run by chefs from Paris and Tokyo. The poor, the elderly, the disabled and the jobless are increasingly prone to Kafkaesque tangles with the bureaucracy to keep public support.

For Emma Wilde, a 31-year-old single mother, the misadventure began with an inscrutable piece of correspondence.

Raised in the Liverpool neighbourhood of Croxteth, Wilde has depended on welfare benefits to support herself and her two children. Her father, a retired window washer, is disabled. She has been taking care of him full time, relying on a so-called caregiver’s allowance, which amounts to about $85 a week, and income support reaching about $145 a month.

The letter put this money in jeopardy.

Sent by a private firm contracted to manage part of the government’s welfare programmes, it informed Wilde that she was being investigated for fraud, accused of living with a partner – a development she is obliged to have reported.

Wilde lives only with her children, she insists. But while the investigation proceeds, her benefits are suspended.

Eight weeks after the money ceased, Wilde’s electricity was shut off for nonpayment. During the late winter, she and her children went to bed before 7pm to save on heat. She has swallowed her pride and visited a food bank at a local church, bringing home bread and hamburgers.

“I felt a bit ashamed, like I had done something wrong,” Wilde says. “But then you’ve got to feed the kids.”

She has been corresponding with the Department for Work and Pensions, mailing bank statements to try to prove her limited income and to restore her funds.

The experience has given her a perverse sense of community. At the local centre where she brings her children for free meals, she has met people who lost their unemployment benefits after their bus was late and they missed an appointment with a caseworker. She and her friends exchange tips on where to secure hand-me-down clothes.

“Everyone is in the same situation now,” Wilde says. “You just don’t have enough to live on.”

From its inception, austerity carried a whiff of moral righteousness, as if those who delivered it were sober-minded grown-ups. Belt tightening was sold as a shared undertaking, an unpleasant yet unavoidable reckoning with dangerous budget deficits.

“The truth is that the country was living beyond its means,” the then chancellor George Osborne declared in outlining his 2010 budget to Parliament. “Today, we have paid the debts of a failed past, and laid the foundations for a more prosperous future.”

“Prosperity for all,” he added.

Eight years later, housing subsidies have been restricted, along with tax credits for poor families. The government has frozen unemployment and disability benefits even as costs of food and other necessities have climbed. Over the last five years, the government has begun transitioning to so-called universal credit, giving those who receive benefits lump sum payments in place of funds from individual programmes. Many have lost support for weeks or months while their cases have shifted to the new system.

All of which is unfortunate yet inescapable, assert Conservative lawmakers. The government was borrowing roughly a quarter of what it was spending. To put off cuts was to risk turning Britain into the next Greece.

“The hard left has never been very clear about what their alternative to the programme was,” says Neil O’Brien, a Conservative MP who was previously a Treasury adviser to Osborne. “Presumably, it would be some enormous increase in taxation, but they are a bit shy about what that would mean.”

He rejects the notion that austerity is a means of class warfare, noting that wealthy people have been hit with higher taxes on investment and expanded fees when buying luxury properties.

Britain spends roughly the same portion of its national income on public spending today as it did a decade ago, said Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

But those dependent on state support express a sense that the system has been rigged to discard them.

Glendys Perry, 61, was born with cerebral palsy, making it difficult for her to walk. For three decades, she answered the phones at an auto parts company. After she lost that job in 2010, she lived on a disability check.

Last summer, a letter came, summoning her to “an assessment”. The first question dispatched any notion that this was a sincere exploration.

“How long have you had cerebral palsy?” (From birth.) “Will it get better?” (No.)

In fact, her bones were weakening, and she fell often. Her hands were not quick enough to catch her body, resulting in bruises to her face.

The man handling the assessment seemed uninterested.

“Can you walk from here to there?” he asked her.

He dropped a pen on the floor and commanded her to pick it up – a test of her dexterity.

“How did you come here?” he asked her.

“By bus,” she replied.

Can you make a cup of tea? Can you get dressed?

“I thought, I’m physically disabled,” she says. “Not mentally.”

When the letter came informing her that she was no longer entitled to her disability payment – that she had been deemed fit for work – she was not surprised.

“They want you to be off of benefits,” she says. “I think they were just ticking boxes.”

An unlikely villain

The political architecture of Britain insulates those imposing austerity from the wrath of those on the receiving end. London makes the aggregate cuts, while leaving to local politicians the messy work of allocating the pain.

Spend a morning with the aggrieved residents of Prescot and one hears scant mention of London, or even austerity. People train their fury on Knowsley Council, and especially on the man who was until recently its leader, Andy Moorhead. They accuse him of hastily concocting plans to sell Browns Field without community consultation.

Moorhead, 62, seems an unlikely figure for the role of austerity villain. A career member of the Labour Party, he has the everyday bearing of a genial denizen of the corner pub.

“I didn’t become a politician to take things off of people,” he says. “But you’ve got the reality to deal with.”

The reality is that London is phasing out grants to local governments, forcing councils to live on housing and business taxes.

“Austerity is here to stay,” says Jonathan Davies, director of the centre for Urban Research on Austerity at De Montfort University in Leicester. “What we might now see over the next two years is a wave of bankruptcies, like Detroit.”

Indeed, Northamptonshire County Council recently became the first local government in nearly two decades to meet that fate.

Knowsley expects to spend $192m in the next budget year, Moorhead says, with 60 per cent of that absorbed by care for the elderly and services for children with health and developmental needs. An additional 18 per cent will be spent on services the council must provide by law, such as refuse collection and highway maintenance.

To Moorhead, the equation ends with the imperative to sell valuable land, yielding an endowment to protect remaining parks and services.

“We’ve got to pursue development,” Moorhead says. “Locally, I’m the bad guy.”

The real malefactors are the same as ever, he says.

He points at a picture of Thatcher on the wall behind him. He vents about London bankers, who left his people to clean up their mess.

“No one should be doing this,” he says. “Not in the fifth-wealthiest country in the whole world. Sacking people, making people redundant, reducing our services for the vulnerable in our society. It’s the worst job in the world.”

Now, it is someone else’s job. In early May, the local Labour Party ousted Moorhead as council leader amid mounting anger over the planned sale of parks.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments