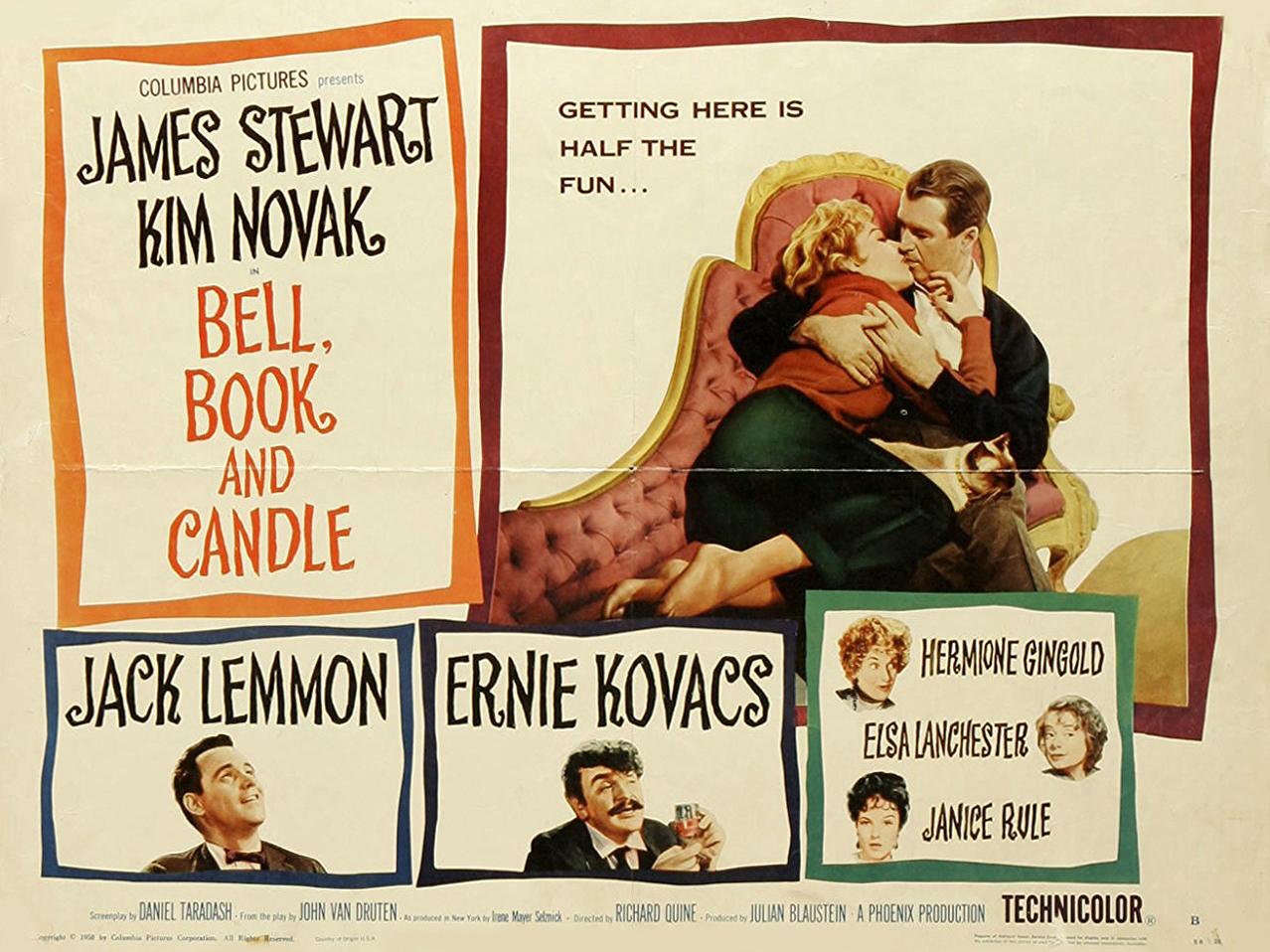

Bell, Book and Candle: Is this the greatest Christmas film ever made?

It rarely gets an airing on TV any more, but this movie starring Jimmy Stewart is one of the best festive films ever, says David Barnett… and no, not the one you think

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Think of Christmas movies, and what springs to mind? Andrew Lincoln stalking Keira Knightley in Love, Actually? Alistair Sim, George C Scott, Michael Caine, Patrick Stewart or Jim Carrey humbugging their way through A Christmas Carol? Will Ferrell’s oversized Elf on a voyage of self-discovery?

Maybe you think of Jimmy Stewart, as I do, and while the claim for It’s A Wonderful Life being one of the best movies ever, not just one of the best Christmas movies, is a hill I’ll gladly die on, it’s not the Jimmy Stewart movie I’m talking about now.

For me, Christmas is witches and warlocks, bongos and beatniks, a classic golden age Hollywood pairing and, hands down, one of the finest and most criminally underrated festive movies of all time. I am, of course, talking about Bell, Book and Candle.

Our scene opens in a shop selling African art and artefacts, where a handsome cat with coldly-burning eyes of intelligent blue leaps on to the shoulder of Hitchcock blonde Kim Novak. Novak’s Gillian (with a hard ‘G’) Holroyd is listless and out of sorts as she wanders around her Greenwich Village gallery-cum-shop at closing time.

She pauses by a very modern Christmas tree, all bronze metal frame and golden baubles, asking her cat – Pyewacket – if he’d perhaps like to get her something nice for Christmas… perhaps the man who lives in the apartment upstairs, and here he is now, head down as he dashes through the falling snow for his door, none other than James Stewart.

Bell, Book and Candle was released on Christmas Day 1958, and was a hit. Today we’d call it a romcom, as Gillian sets her sights on Stewart’s New York publishing executive Shep Henderson, but it had an altogether dark flavour. For one thing, Shep is due to marry his fiancée Merle on Christmas Day. For another, Gillian – along with her eccentric aunt Queenie (played by the original Bride of Frankenstein, Elsa Lanchester) and her brother Nicky, a superb turn by Jack Lemmon – is a witch. Not a nose-twitching sweet-as-apple-pie domestic witch like Samantha in Bewitched (the TV series which creator Sol Saks freely admitted was inspired by Bell, Book and Candle), but a proper, black magic, sinister spells witch. She even has a familiar, dear Pyewacket the cat, named for one of the impish spirits the notorious Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins claimed to have uncovered among a coven of witches in Manningtree, Essex, in 1644.

Gillian finds herself falling for Shep in a big way, despite warnings from her family that for a witch to fall in love with a mortal will mean giving up her powers. But it’s Christmas, and she’s bored; besides, she was at school with Shep’s girlfriend Merle, and the two have a history that means we, the audience, don’t feel quite as badly towards Gillian as perhaps we should when she brings her witchy powers to bear on poor old Shep.

If it sounds daft and comic, it’s anything but. The film isn’t played for laughs, not even Jack Lemmon’s part as mischievous warlock Nicky, who hangs out with his band at the Zodiac Club, rolling his eyes and banging his bongos cross-legged on the stage in this very Greenwich Village haunt of New York’s witches. It’s a very Hollywood vision of the bohemians and beatniks who were fascinating America at the time – Jack Kerouac’s On The Road had been published the year before – but it fits perfectly if perhaps rather inexplicably with the whole feel of the movie. If witches were real in 1950s New York, it stands to reason they’d celebrate Christmas Eve in a jazz speakeasy.

Another major part in Bell, Book and Candle’s success is the hue-saturated Technicolor filming. Colour movies had been around for a good 20 years, but they still weren’t the norm by 1958, and it’s the cinematography that particularly captured the eye of The New York Times’s critic Bosley Crowther in his review of the premiere, published 27 December.

Crowther said the movie was “as sleek and pictorially entrancing as any romance we’ve looked at this year. From the atelier of the heroine, who is a dealer in primitive art, to a smoky night club in Greenwich Village, where the local sorceresses and their apprentices play, it is vividly visual and suggestive.

“They [art director Cary Odell, colour consultant Eliot Elisoforn and cameraman James Wong Howe] have done things that hypnotise the eye. To give you an example, they suggest how things look to the witch’s cat by saturating camera-distorted images in a deep melancholy blue. And what they have done with New York street scenes at dawn and twilight is necromancy.”

But the real magic comes from the chemistry between the leads. Stewart and Novak had already made waves in 1958 in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, with Stewart as the acrophobic former police detective hired to tail an old friend’s oddly-behaving wife, Novak as the ethereal Madeleine. Stewart is less neurotic (but still as charmingly dithery) than in Vertigo, but Novak has a presence that fills the screen with as much sorcery today as it did 60 years ago.

Bell, Book and Candle originated as a stage play which ran for a year on Broadway with Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer in the roles of Shep and Gillian. The film rights were optioned by Columbia and original writer John Van Druten’s stageplay was adapted for the screen by From Here To Eternity writer Daniel Taradash. The studio originally wanted Harrison to transfer from the stage to the screen but, busy with other projects, he had to decline and Stewart was brought in to reprise his earlier on-screen pairing with Novak.

The whole cast, including the comedic actor and writer Ernie Kovacs, who plays a slightly slobbish author investigating New York’s witch community for a sensationalised new book, tread a fine line between spookiness, comedy and melodrama to make this a quite singular movie, though Lemmon apparently said years later that it was one of the least favourite films he made. Perhaps that shows in his character Nicky who hams up his part, especially the magic scenes, in a way that Novak, always ice-cool and melancholy, never does.

Aside from the stellar cast and the cinematography that so entranced The New York Times, Bell, Book and Candle (which, of course, takes its name from the Catholic tools of excommunication; original playwright Van Druten liberally applied it to mean dealing with spirits, exorcism and witches) is also a thumping good story which raises many moral issues.

Is it right for Gillian to steal Shep away from Merle, even if Merle was a bit of a cow back in the day? Does bewitching someone into loving you still count as real love? And is love ever worth giving up everything – Gillian’s witchy powers – for?

Perhaps Bell, Book and Candle could have been told without it being a Christmas movie, but I tend to think not. Though a season of joy and goodwill, it’s also one entwined with darker things, with ancient traditions, with tales of ghosts and, indeed, witchcraft. When a beguiled Shep stands on top of the Flat Iron Building with Gillian in his arms, a snow-covered New York in the early hours of Christmas Day spread out before them, and tosses his hat to fall down to the street, he says, “There’s a timelessness about this. I feel spellbound.”

It’s the magic of Christmas, of surprises, of possibilities, of taking a sideways step away from the normality of everyday life. It’s something that can’t, and perhaps shouldn’t, last beyond the moment, as Shep discovers when he realises his feelings for Gillian are the product of forces beyond his control. There are some hiccups when Shep realises he’s been played, and some serious choices to make for both him and Gillian. But, this is Hollywood, and Christmas, and love does eventually conquer all.

So, forget a white Christmas, just give me some of that ol’ black magic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments