Do we have Obama and Blair to thank for Trump and Brexit?

It might be called Newton’s third law of politics – that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. But, as John Rentoul explains, sometimes politics can be more complicated than physics

Did Barack Obama cause Donald Trump’s presidency?

The question is raised in Dan Pfeiffer’s memoir of his time as Obama’s press secretary, called Yes We (Still) Can. It is a wonderful book, energetic, honest and self-mocking. As a connoisseur of footnotes, I enjoyed the way Pfeiffer uses them to heckle himself. For example, he tells a story of his childhood about how he cheated at Trivial Pursuit. “I would take the cards with the questions from the box and go into my room and memorise the answers.” Thus at the age of 10 or 11 he was able to answer all the questions, including which movie won the Best Picture Oscar in 1944. At this point a footnote interjects: “It’s not that hard. The answer is Casablanca, the only movie that old that anyone has heard of.”

Ultimately, the book is upbeat – hence the title. “The good news,” he says, about the way the Republican Party “weaponised racial anxiety” to motivate its base, “is that this is not a sustainable strategy in a country that is getting more diverse by the minute. Obama’s America is the future. Trump’s America is the last throes of a bygone era.”

Before that, though, there is a striking passage from the middle of the Obama presidency: “The Republicans repeatedly declared war on Obama, but Obama usually came out on top… His agenda was in line with the majority of the American people. And he was smarter and better than the Republicans.”

But there was a “but”, which is the bit that made me wonder: “Every Obama win came at a long-term cost. The Republican base got angrier and more radicalised. Not just at Obama, but at their own leaders. Faced with this revolt, Republicans like Ryan and McConnell decided to accommodate the crazy instead of confront it.”

Pfeiffer tells of Republicans in Congress who wouldn’t accept invitations to a bipartisan dinner at the White House because “they were petrified of being tossed out in a primary challenge if they were photographed treating Obama like a human being … Their voters hated Obama so much that it paralysed the Republican Party.”

That led, in Pfeiffer’s view, to “the plague that has infected the Grand Old Party”, and made a Trump presidency possible. Trump is a symptom, says Pfeiffer; he is not the disease. He didn’t take over the party; he is the end result of a party that reacted to Obama’s presidency by turning to the “rabid fringe”.

Surprising support for this thesis came from Jacob Rees-Mogg, the Conservative arch-Brexiteer, just the other day. Obama “was part of the political elite that created the circumstances that allowed Donald Trump to come through”, he said. “Obama should look at himself and what he got wrong, rather than put all the blame on Trump. The situation had to be created and eight years of Obama might have helped.”

Indeed, I had forgotten that the Tea Party movement started as a direct response to Obama’s inauguration in 2009. It was prompted by the incoming president’s announcement of a bailout for homeowners suffering from the collapse of the subprime mortgage market – although opposition to Obama’s healthcare plan quickly became the main focus of the campaign. This led, in an erratic but continuous line, to the election of Trump seven years later.

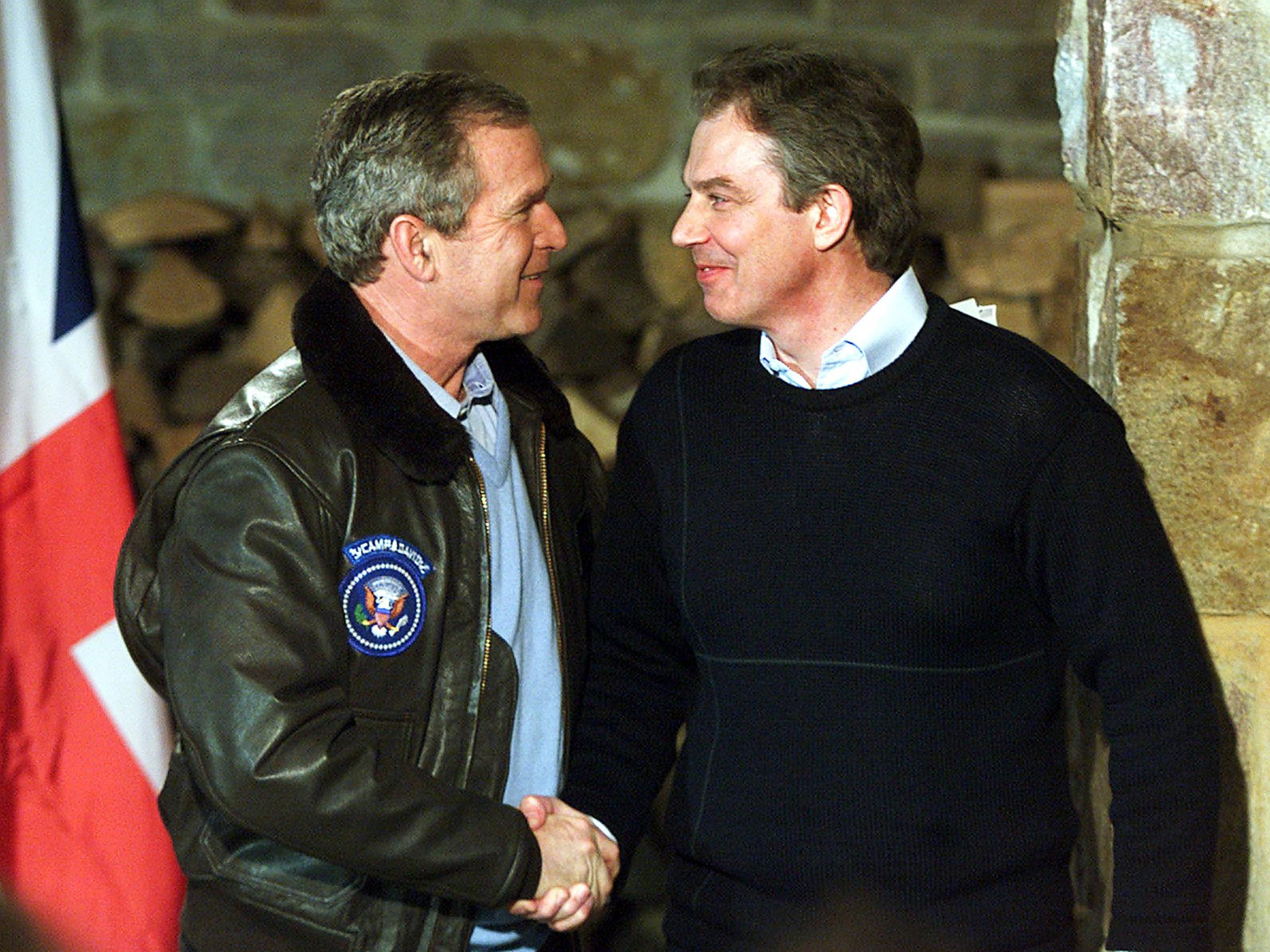

This might be called Newton’s third law of politics: for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. It reminded me of the Jeremy Corbyn phenomenon in Britain. This seems to have been almost entirely a reaction against Tony Blair and his long ascendancy. Everything about the Corbyn movement is defined, in the minds of its supporters, as the opposite of what Blair did. Blair was war; it is peace. Blair was neoliberalism; it is socialism. Blair was for the rich; it is for the poor. Blair was for privatisation; it is for nationalisation. Never mind that this is a historical fiction, it is the emotional force behind Corbynism.

In fact, the parallel is more complicated, because the closer American analogy to Corbyn is Bernie Sanders, a fundamentalist left-wing reaction to the compromise and pragmatism of Obama. The main difference between Corbyn and Sanders being that Sanders failed to become the candidate of the main left-wing party in a general election. (For all that Hillary Clinton was derided, she did at least manage to win the primaries; whereas Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall contrived to lose to Corbyn.)

On this reading of history, the equivalent of Trumpism in Britain was the other delayed reaction to Blair, namely Brexit. It is often argued that Blair caused Brexit by opening Britain to immigration from central Europe when the EU expanded in 2004. It is also possible that his pro-EU stance generally and his advocacy of the euro stoked the fire. One shovelful was his promise of a referendum on the EU constitution, which he dropped when a watered-down version of the constitution became the Lisbon Treaty.

Craig Oliver, David Cameron’s press secretary, called his memoir Unleashing Demons – a reference to his boss’s fears about promising an in-out EU referendum – but it is arguable that Blair had already let out the demons from the caverns in which they had been imprisoned by the long decades of pro-EU consensus.

It could be argued that Obama and Blair each provoked a double backlash: a nationalist one (Trump and Brexit) and a supposedly left-wing one (Sanders and Corbyn). All four movements are literally reactionary; all of them have deployed similar rhetoric to attack a system “rigged” for the benefit of the “elite”.

We have had pendulum politics before: the old idea that power would alternate between the parties. As one got into government and became unpopular, it would be replaced by the other, and then the pendulum would swing back again. And we are familiar with the idea that public opinion moves in cycles. Professor John Curtice has pointed out that attitudes to tax and public spending ebb and flow. After the stringency of the Thatcher years, more people supported higher taxes and spending; after the years of New Labour plenty, attitudes reversed; now, after years of so-called austerity, the wheel is turning again.

But what we might call the Pfeiffer thesis is that the very success of pragmatic social democracy drove its opponents to extremes. The more it succeeded, the more trouble it stored up for the future, until it produced movements that were a sharp break from what went before.

The point about the four horsemen of the reactionary apocalypse – Trump, Sanders, Corbyn and Brexit (the latter a sort of composite person made up in equal parts of Nigel Farage, Boris Johnson and Michael Gove) – is that they are different from politics as usual. So the Pfeiffer thesis is actually different from Newton’s third law: instead of producing equal reactions, Obama and Blair seem to have provoked disproportionate and extreme ones.

Every Obama win came at a long-term cost. The Republican base got angrier and more radicalised ... Faced with this revolt, Republicans decided to accommodate the crazy instead of confront it

Trump and Brexit are part of a global movement that Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin call “national populism” – the title of their new book – which is seen as being more right wing than traditional conservatism. Meanwhile, Sanders and Corbyn represent minority traditions regarded as well to the left of their mainstream parties.

The mystery about Sanders is why he was so popular among Democrats after two terms of an Obama presidency, when his politics were utterly marginal after two terms of Bill Clinton. It seems that the “normal” politics of Obama and Blair, tilted to the left side of the centre, provoked a reaction that was different from the swings of the pendulum that had happened before.

Pfeiffer spends much of his book struggling with the question: why was it different this time? He describes his confusion, as a spokesperson for a politician, facing the new media environment. Although the Obama campaign was tech-savvy, once it was in the White House it was caught unawares by the effect of Facebook: “For most of my time working for Obama, whenever we encountered some Beltway political crisis that dominated cable news, we would ask focus groups of voters if they had heard anything about it. Almost every single time, they had no idea what we were talking about,” he says.

“But something had changed. Suddenly, focus groups knew all about the trivial things that Washington would get worked up over, and they knew them in great detail. Often reading back to the moderator what sounded just like Republican talking points or a Fox News story – which are actually the same thing.

“When the moderator asked them where they’d learned this information, the answer was almost always the same: Facebook.”

Pfeiffer concludes: “In hindsight, it seems obvious that Trump would thrive in this environment. The hints were there all along, going back way before he even ran.”

But Facebook was only the start. It fed the new rabidly partisan republicanism that lifted Trump up, but it was Twitter that took him over the top to victory.

“Without Twitter, there is no President Trump,” says Pfeiffer. “Twitter facilitated a coarser, less substantive political culture that significantly benefited Trump, who is at his very core a Twitter troll.”

Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, “was a serious policy wonk who didn’t love to put her guard down. She was a politician from a time before Twitter – and frankly before the internet. Throughout the 2016 campaign, Twitter never felt like a natural fit for her. She had never participated in and consumed Facebook, Twitter or Instagram like a civilian.

“This put her at a disadvantage against Trump, who is legitimately good at Twitter, because, for good or for ill, he is his authentic self on Twitter,” says Pfeiffer. “Authenticity is the coin of the Twitter realm.”

Actually, authenticity has always been important in politics, so this raises the question: did the national populists just exploit the new media, or did the new media create national populism, as Pfeiffer implies?

Francis Fukuyama, the thinker who thought the triumph of liberal democracy marked the “end of history” but who has since recanted, asked this very question recently: “Social media is perfectly made for identity politics. It allows you to close yourself off in an identity group, get affirmation of everything you say, and not have to argue with people who think differently. It’s hard to tell what’s cause and effect. I used to think that the driver was society itself, and that technology only accelerated it. But I’m beginning to think causality moves the other way: that we wouldn’t be where we are if not for the internet and social media. This is something future historians will have to unpack.”

We can make a start on taking the wrapping off now, though. Plainly, the internet and social media have allowed the expression and wider dissemination of views that were previously confined to small groups, to letters to newspaper editors (selected and edited) or to radio phone-ins. That must have had some effect on political culture, and we can assume that by amplifying and connecting marginal voices it has strengthened them.

This could just be a change of degree rather than of kind, however. In the US there were precursors to Trump. Ross Perot ran as an independent presidential candidate in 1992, winning 19 per cent of the vote; Newt Gingrich captured Congress with the populist Republican Contract With America; Pat Buchanan, “the Republican with a pitchfork”, came second for the Republican nomination in 1996; and Sarah Palin was the vice-presidential nominee in 2008.

When John McCain died last month The Independent’s own Matthew Norman wrote that, by choosing Palin as his running mate, he was “the unwitting midwife at the birth of proud and impenetrable ignorance as a winning electoral weapon”. Well, no, her selection was part of a long-running and intermittently strengthening trend in American politics.

Nor did Brexit come out of the blue in Britain. The Conservative Party had been riven by Europe since Margaret Thatcher’s fall, and the first three opposition leaders in the New Labour years – William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard – were all “Eurosceptics”, although that mostly meant opposing the euro rather than EU membership itself. Cameron got his party to “stop banging on about Europe” in opposition, but in government he faced a rebellion of 79 Tory MPs, demanding a referendum, as early as October 2011.

One very popular argument is that national populism represents one ‘last howl of rage’ from old white men soon to be replaced by tolerant millennials

It could also be that the success of right-wing and left-wing populists in Britain and America was the result of arbitrary events and personalities. It could be that Trump just got lucky to hit a weak Republican field in the primaries; and that the Leave campaign prevailed because Boris Johnson decided in its favour and Dominic Cummings fought a ruthlessly focused campaign.

Bernie Sanders may have benefited as much as Trump did from Hillary Clinton’s weaknesses as a candidate of change; while Corbyn’s success does seem very much like the product of a catalogue of accidents and mistakes. Ed Miliband’s rule changes; the nominations from MPs to “widen the debate”; and then the disastrous Conservative election campaign of 2017.

Yet there does seem to be something deeper happening. That is why Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, in their book, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, published in October, cast doubt on Pfeiffer’s optimism. “One very popular argument,” they wrote, “is that national populism represents one ‘last howl of rage’ from old white men soon to be replaced by tolerant millennials.” They seem more sympathetic to the competing view that “national populism is only just getting going as the bonds between the people and the traditional parties fray” and concern about immigration rises.

As a sunny social democratic optimist, with a whiggish belief in progress, I lean towards Pfeiffer rather than Eatwell and Goodwin, but I do think that Pfeiffer is confused about Trump. In the end, I don’t think that Obama is “to blame” for Trump. I think Trump won because he was a strong national populist candidate in a new media environment and he got lucky. Ed Balls’ recent documentary in search of Trump supporters was fascinating: nearly halfway through the first term, what sustains Trump’s base is an economic boom and a hardcore message against immigrants.

The connection between Blair and Brexit is more obvious: if he had delayed the free movement of central Europeans for seven years after 2004, as EU law allowed, then events might have worked out differently. Even then though, the pressure to leave might have built up eventually. The rise of Sanders-Corbynism, what might be called socialist populism, was caused by a similar combination of accident and reaction to what went before. The lesson is that politics goes in cycles, but they don’t repeat themselves exactly. Victories produce backlashes; and arguments that leaders thought they had won turn out to be quickly forgotten and have to be painfully learned again. As Fukuyama learned, no victories are final and history never ends.

‘Yes We (Still) Can: Politics in the Age of Obama, Twitter and Trump’, by Dan Pfeiffer, is published by Biteback Publishing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments