Those who despair of America's gun culture must examine its history

Despite the deaths of 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February, the US gun lobby continues to look to the past to prevent measures that would restrict modern gun ownership

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

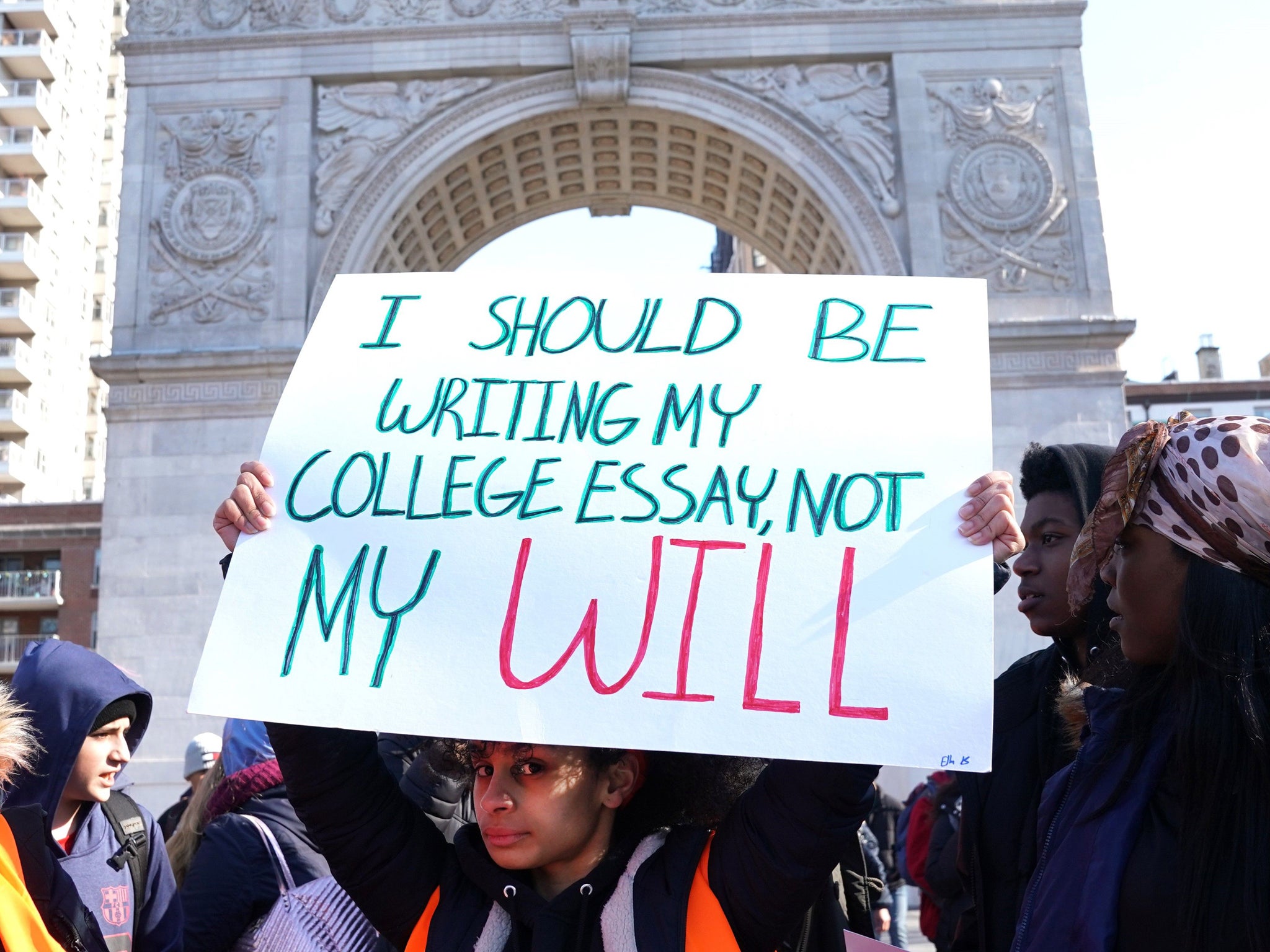

Your support makes all the difference.The recent school shooting in Florida claimed the lives of 17 individuals, most of them teenagers. The fact that this story did not remain in our headlines for more than a couple of weeks; the fact that little political action has been taken in the aftermath; and the fact that, in some ways, American school shootings no longer seem as shocking as they once did, are all indicative of the state we are now in.

Once upon a time, an American school shooting would lead to lengthy debate, a national crisis of conscience and a forensic analysis by American news anchors of the shooter’s life, their motivations, the lives and deaths of their victims: much of this reflected in the British media. That no longer seems to be so.

The tragic frequency of such events now means that these massacres seem inevitable in their occurrence, their political fall-out minimal, and it being a question of “when” rather than “if” there will be another such crime.

The attack in Florida was the eighth school shooting resulting in injury or death to have occurred in the United States in the first seven weeks of 2018. When such events occur on multiple occasions, they inevitably begin to have a more limited effect on the public conscience.

America is now in the dubious position of being the only industrialised country where the frequency of such attacks is so great that the presentation of each individual tragedy in the British media feels ever closer to the way suicide bombings in the Middle East or in Afghanistan are covered: just another passing presence in the daily news reports of death and tragedy in foreign fields.

Donald Trump’s reaction to the recent massacre in Florida suggested that there would be little in the way of political change arising from this shooting: the NRA is too entrenched, there are too many political positions at stake. In the aftermath of the 2013 Sandy Hook shooting, Barack Obama called for “common-sense gun safety measures”. However, these were blocked by Congress at the time. Thereafter, there continued to be legislative intransigence in passing laws aimed at gun-control. If young children being gunned down in a massacre doesn’t result in political change, what will?

The truth is, Second Amendment rights to bear arms remain entrenched; the gun-lobby all powerful. Tragedies notwithstanding, the gun remains at the heart of American public life.

Of course, we should not forget America’s peculiar history and the central role the gun played in the invasion and subsequent conquest of the landmass known as the United States. The fact that guns were instrumental in enabling both this conquest and the subsequent efforts of the United States government to detach itself from British rule in the 18th century – combined with the development of the “small state”, individualistic model of governance – goes some way to explaining the continued presence and acceptance of firearms.

Unlike the vast majority of other industrialised countries, the gun is a common presence in many otherwise “normal” homes in the US, across all classes. This is a situation that simply does not exist in most Western, and indeed many Eastern, nations.

In America, the police are armed, some prison officers are armed, some states allow for the “open carry” of firearms and others allow for the carrying of “concealed” firearms. All this in a highly developed country in which there is a functioning government, no civil war or anarchy, and a developed infrastructure.

None of this can be understood without reference to the historical narrative of the United States.

Ironically, the Second Amendment came into being out of concern that there ought to be a “well regulated militia”; however, this provision was created at a nascent stage of the United States’ development. Fast-forward to the present day, and President Trump is seeking to increase American defence spending to $716bn (£505bn) per year.

In the face of this phenomenal American military might, it is absurd to suggest that private citizens owning firearms somehow act as a safeguard to the state’s potential encroachment on individual rights. If the American army wished to overpower its people, it could do so swiftly and with ease: it is democratic principles, the rule of law and legal norms that prevent the American state from doing so, not the fear that individual citizens would use handguns against the authorities.

Nevertheless, when the topic of gun ownership arises in debate, it is such emotive sentiments which are often to the fore: that guns are needed to stop an omnipotent state; that if guns were taken away from the “good” guys, only the “bad” guys would have guns.

An inherent tension, then, exists between the historical context with which Americans find themselves laden, and the reality of firearms causing widespread destruction. This tension is something that many American presidents are acutely aware of, especially in relation to the political power wielded by the National Rifle Association. Barack Obama was aware of this, as was Bill Clinton, who wrote in his 2004 autobiography My Life that “no southern state would say no to the NRA”.

Indeed, it is not only southern states that are at the mercy of the NRA: the political, financial and wider public influence the NRA can wield across America is often cited as one of the primary reasons for the failure to make much progress when it comes to gun-control measures. The Second Amendment is, say gun rights activists, clear in its phraseology: “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed”.

However, the American Constitution was written at a time when AK-47s and sub-machine guns did not exist. Moreover, urban gang warfare, crack cocaine, widespread youth violence and ghettoisation were not problems at the time of the Constitution’s creation. Many other significant internal and external factors have germinated in the centuries since the American Constitution’s creation in 1787 too.

In more recent times, there have been a few federal court rulings in favour of the regulation of gun-ownership: as I wrote in 2007, these federal rulings, combined with the Supreme Court largely remaining silent on Second Amendment issues, led to gun-control measures being maintained in some American cities such as Washington DC and Chicago.

However, the overall national picture continues to remain overwhelmingly pro-gun: the only two pieces of federal legislation restricting gun ownership in the past twenty years have been the Brady Bill of 1993 and the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994.

As regards the broader, criminological debate, there has been a growing movement to render anonymous the identities of shooters, depriving them of the publicity they crave. Indeed, there is an argument that suggests the motivations of mass-shooters should not be analysed in isolation from the wider debates around murder-suicides, and fatal crimes more generally.

Although there is an increasing focus on the political or ideological motivations behind some such shootings, the “random” massacre is the most difficult to unpick, and the subsequent governmental inaction bewildering. Such “random” shootings are the most baffling, in part because of their seeming lack of causation and the absence of any concrete factors that motivated the shooter, outside of the desire to kill.

In his book They Wrought Mayhem: an Insight into Mass-Murder, criminal psychologist Andreas Kapardis presents a number of case studies describing how guns have been used by mass-shooters in a number of countries. The nihilism and violent intent act as themes that unify the actions of many of these shooters. However, it is the aftermath of such incidents that are indicative of the different responses which countries take to the phenomenon.

In the United States, the saying “guns don’t kill people, people kill people” seems hollow in the face of the growing body count: if people who seek to kill have more ready access to firearms, then these guns will be used by them to kill more people than otherwise would have been the case. In the UK, that painful lesson was learned after the Hungerford and Dunblane massacres; similar lessons were taken on board in Australia. No such lessons have been learnt in the United States of America. Yet.

This analysis may do little to bring concrete policy action in the US, or closure for the parents of the children whose lives were claimed at Stoneman Douglas High School in February. Perhaps it is only with the passage of time, as America moves away from the foundations of its history that the importance given to guns will hold a less central place in the American psyche.

Maybe the protests across the United States will mark the beginning of a gradual change in public and political sentiment towards the gun issue – and maybe they will not. And, if not, then maybe we will all just have to wait, for more years to pass, and for countless more lives to be lost, before it becomes accepted political wisdom in the United States to adopt an approach to gun-control and firearm ownership that is political orthodoxy in the world’s older developed countries.

And what a painful wait that will be – for all concerned.

Dev Maitra is a criminologist and writer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments