For my mother the actress, Alzheimer’s is one role she simply cannot escape

Who is this person who seems so much like my mother, who performs her so well, even without knowing the correct lines to say? Kate Neuman watches as Nancy slips away

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I sit across from my mother in the paisley-papered dining room of the assisted living facility and try to follow her flow of words. It’s like watching acrobats on trapezes, swinging and releasing and somersaulting through the air and catching again in dizzying arcs, or like tracking an Asteroids player’s little white spaceship as it drops and twists, disappearing and reappearing on the other side of the screen. I will think I’m with her, secretly triumphing in my ability to make sense of the nonsensical leaps and ellipses, but then I lose the thread, miss the jump. I don’t give up, though. I throw her a “Really?” or “When was that?” and she’s off again.

Here’s the amazing thing: if you could see her – animated and gesturing, leaning in, smiling, shaking her head no, nodding yes, making eye-contact – and hear only the sound of her speech, if the words were somehow muffled, you would think that she was having a normal conversation. There is something magical in how my mother manages to seem perfectly coherent until you pay attention to what she’s saying.

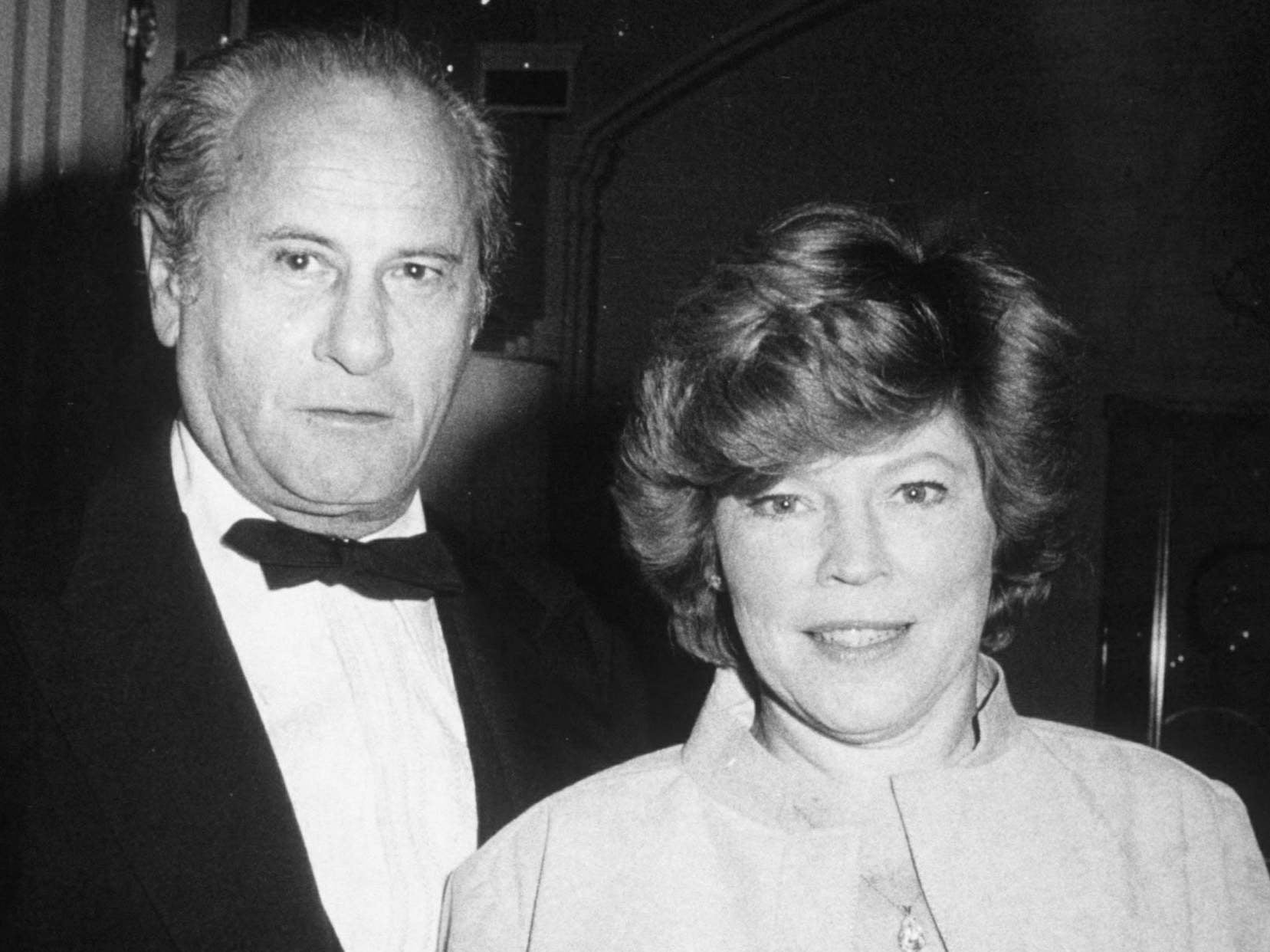

Maybe it’s just that the act of performance is so basic to her that it’s more deeply ingrained, more deeply or variously remembered than the words, themselves, and so content becomes irrelevant. My mother has been an actress since she was 19; she didn’t stop until three years ago, at 82, when her Alzheimer’s wouldn’t allow her to remember lines, anymore. She’s been on soaps, nighttime episodics and Broadway. She was successful enough to have been blacklisted by McCarthy. She was never famous, but, if you’re a certain age, she might look familiar.

She says: “I think it’s wonderful especially because of all the lucky nails and lucky all those things that they’re pushing pushing pushing pushing, which I think is very nice.”

“Absolutely,” I say.

Acting is, among many other things, permission to leave yourself behind. Your responsibilities are no longer to friends and family. Before you go on, you sit in a chair, or stand somewhere, and release tension, through your voice, through motions; you relax out of your identity, letting your so-called real life fall away so that you can completely inhabit the life you will create. We say that a good actor disappears into the role; this disappearance is intentional, the consummation devoutly to be wished.

After two hours, you return to yourself, your life, your concerns, but, while you are on stage, it’s as if they never existed.

“How do we know each other?” my mother asked as I made the turn on to Main Street in Great Barrington. She asked with the air of an old friend wanting to find the shared memory, an invitation to reminisce.

This was two years ago, when she was still living in the house in the Berkshires that she and her common-law-husband, Connie, had originally bought as a summer home. I had come by to take her to coffee in the nearby town. I was conscious of my hands on the wheel, and the shifting street scene framed by the passenger seat window behind my mother’s head as I turned to look at her.

“Are you serious?” I asked. “Yes,” she replied earnestly. “I can’t remember how we met.”

I stayed conversational: “Well, I’m your daughter.” Her already large eyes widened. “You are?”

“Yep.”

She shook her head wonderingly. “I had no idea.” Ten minutes later, sitting across from her in the dark panelled café hidden behind the high-end provisions store, I took stock of how my world view had changed since the moment before she asked me that question.

Who am I, I wondered, if my mother doesn’t know me?

I’m an only child, as is my mother; we were a team, a duo: Nancy and Katie. We spoke in a private shorthand curated from books we read, movies we saw, stories she told – any quasi-memorable event was grist. Our secret codes evolved as we used them, so that a gesture as small as a lifted finger could contain a library’s worth of history, reducing us to helpless giggles whose source was obscure to anyone else who might be with us, and maybe, for me, at least, that was always part of the point.

We sometimes played a theatre game called Essences as we drove places in the car, or rode buses, or sat in taxis in New York traffic. One of us would think of a famous person and become him or her as the other asked, “If you were . . .” questions.

“If you were a colour, what colour would you be? If you were a type of music, what type of music would you be? If you were an animal, what animal would you be?” Our minds moved along the same paths so closely that I would know that dark red and fox and samba must be Lauren Bacall, and she would get right away that blue and sunny skies with a brisk wind and Shaker bench was Pete Seeger.

My mother onstage was a puzzle in the way of an Escher drawing: impossible, yet true. She was my mother, of course, but/and she wasn’t. She was someone else, who didn’t know me, whose life I was not a part of

From the time I could sit still long enough, I went to see every play my mother did. As I walked into the theatre lobby, I’d feel the heat of the secret that I wanted to shout out, but also keep: my mother is in this play! If her headshot was up on the wall, I’d stand looking at it and wonder if anyone could guess.

My mother onstage was a puzzle in the way of an Escher drawing: impossible, yet true. She was my mother, of course, but/and she wasn’t. She was someone else, who didn’t know me, whose life I was not a part of. I’d feel a little tug – a desire to catch her eye, to wave to her. After the play ended, I’d head backstage to wait for her. When she came out from her dressing room, she’d make a bee-line for me and hug me tightly. I’d see traces of the pancake stage makeup in the hairline above her ears, and I’d smell the strange cakey scent of costume and stage lights and backstage dust lurking under her White Shoulders perfume.

Or maybe it was me hugging her tightly. Sometimes she’d whisper: “Was I OK?” I’d whisper back: “You were wonderful!” Then, arm in arm, we’d go out to dinner.

When I was young, my mother went out of town to do regional theatre tours often. She would be gone for two months at a time, beginning from when I was about three and continuing on more of less regularly as I grew up. I don’t remember missing her, but I do remember her returns, and the sudden wash of joy and relief and sense of completeness at having her home again, as if I had been gone, too, without knowing it. Much later, I would realise how badly her absences had affected me – I spent my thirties spitting-angry about them – but, at the time, it seemed fitting that her work took precedence over everything else. I was her biggest fan.

And, of course, I wanted to be an actress. I have a vague memory of briefly considering becoming a nurse, or a ballet dancer, but those desires were casual. As soon as I was in my first school play, I knew for sure I, too, had been called to a life in the theatre. I’ve been at it, on and off, since then.

Tuesdays at 6pm my mother and I would catch the Second Avenue bus, or, if she was running late because of an audition or rehearsal, hop in a cab, and head to a place called The Loft, where our improvisation group met. In the early 1970s, Noho didn’t have a name, other than “downtown”, and it was derelict and trash-tossed and junkie-strewn. Our group, an array of downtown-theatre-scene adults with a few children mixed in, met on the vast top floor of a walk-up on Bond Street. We could see the Empire State Building out of the huge chicken-wire-paned windows.

My mother and I would clank up the stairs, shoving the heavy door open. “Hello, hello!” she might call out. Everyone was always a little early, and ready to work, shedding coats and bags on to the bent metal folding chairs that we’d pull over to the north end of the loft, so that our backs were to the view.

The session would start with a group warm-up. We’d walk in imaginary peanut butter and throw a ball made of air back and forth. After the warm-ups, we’d start doing improvisation games, in twos or threes.

The hardest thing about improvisation is how relaxed you have to stay. You have to be open to whatever comes your way. The first rule of improv is never negate. You say, “Yes, and...” instead of “No,” accepting whatever the other actor on stage suggests, going with it, not questioning it, so that you are creating, in the moment, together. You can’t plan anything in advance, because that will take you away from whatever is actually happening. You have to not try.

You have to trust yourself – that whatever occurs to you in the moment is OK, that you are OK, without editing, and you keep going until someone watching calls “Blackout!’ and the scene is done. This kind of freedom from self-examination has never been my strong suit, and certainly wasn’t when I was 10. Although I loved the workshop and looked forward to it all week, to this time of being like a real actor, I often felt that I’d messed up in whatever exercise I’d just done; and I knew that thinking in terms of “messing up” meant that, indeed, I had.

I understand that the idea of improv is to train the actor to be in the moment on stage, so that, even when you do have a script, you are living the play for the first time, and, of course, the spontaneity this encourages is what makes theatre thrilling. But what I love about acting, or one of the things, has always been the safety a script affords me; unlike in real life, where I never know how anyone will react to what I say, onstage I relax because there are lines that must be spoken and blocking that must be followed, and any surprises are contained within an agreed-upon field.

Improv’s purpose is to erase those boundaries; the result is, for me, a little too closely related to the profoundly terrifying actor’s nightmare: that dream all actors have at some point in our lives, and often recurringly, in which you are onstage, but you have no idea what play you are in or what your lines are, and you have to try to get through the performance, somehow.

That dream all actors have at some point in our lives, and often recurringly, in which you are onstage, but you have no idea what play you are in or what your lines are

I guess one difference is that, when you do an improv, you know that someone will eventually call, “Blackout!” In an actor’s nightmare, you don’t believe that there’s ever going to be an end.

At the Loft, we used to play a game called Gibberish. Two people begin a conversation. After a few minutes, a third person says, “Switch!” and the two people continue their conversation, but now speaking nonsense syllables, or gibberish. A few minutes later, they switch again, and the conversation continues in English. And back to gibberish again, and English again, and again. The objective is to communicate authentically even though you’re not speaking a recognisable language, and you do that by focusing on your partner and the response you are receiving, rather than on what you are feeling, yourself.

I used to fake Gibberish a lot. I would act as if I were really talking about something when we switched out of English, but all I was thinking about was whether anyone could tell that I wasn’t really talking about anything, and so I would be completely lost when we switched back. I’m very good at it, now, though.

“Did you just finish breakfast?”

“Oh, yes. I was there. It was lovely. All the people did those things, you know, the grr grrr and ptcha ptcha things, you know, when they, and, so we didn’t, oh, you know what I mean . . . .”

Switch! “Oh, sure. Was that nice, or did you not like it?”

“Oh, no, no, it was. It was just lovely.”

“Did you sit at the big round table?”

“Oh, well, the man who brought the thing to um now for the rrrrm vrrrrp and it was, oh, you know, but never there in that way that other, you know.”

Switch! “That sounds nice.”

“Oh, yes, it really was.”

Our improvisations, which started out as brief moments in longer conversations, grow longer and wilder as my mother’s brain’s power is increasingly short-circuited. I keep them up because our tacit agreement to agree, our continuing commitment to never negate, gives us a point of deep and familiar contact – and because, every once in a while, something real pops to the surface that I can hold on to for a moment – although if I put any weight on it, it sinks, leaving me floating on my own in deep water.

“What are you going to do now?”

“Oh, well, Conrad Bromberg is here, and we’re going to ... do that ... thing.”

I am stopped for a second by a rush of something that resembles hope, although there’s really nothing to hope for, no positive progress that can happen; the best we get are those brief moments of clarity that are inexplicable and unsummonable. I haven’t heard her say Connie’s full name in a long time; she usually only says his name at all if I’ve asked about him by name, as in, “How’s Connie?” to which her first response is usually, “Who?”

“You mean Connie?” I want to see if she knows who she’s talking about.

“Yes. Him. He comes here quite often.”

You would think by now I would have learned that expectation never works in improv, that I would let us both off the hook, but you would be wrong:

“Mom, do you know Katie Neuman?”

“Oh, well, I don’t know. It sounds familiar. What is it?” She is playing along, doing her part the best she can, but she has misinterpreted the cue, and I am suddenly an “it” rather than a “who.”

“It’s me!” I try to sound like I’m giving her a surprise. “That’s my name.”

My mom laughs. “Really? How wonderful!”

And yet she is still so fully herself! That’s what gets me, what lays me out for days after I see her or just talk to her on the phone. Even without any memory, without logic, her character is clear – she is Nancy: her gestures, her tone, her still crystal-clear enunciation, her inflections, are as easy to identify as ever; her sense of humour, her eagerness, her engagement with the world around her, seem, for the most part, unchanged.

I am amazed that this is so. How is it possible? Who is this person who seems so much like my mother, who performs her so well, even without knowing the correct lines to say? Who looks at me with my mother’s light-bright eyes, yet doesn’t know who I am? Does the performance of her have the same validity as the reality: the person who knew where she came from, and what she’s done, and whom she loves?

Does the performance of her have the same validity as the reality: the person who knew where she came from, and what she’s done, and whom she loves?

“I hate you!” I yelled at my mother. I tried to keep the tears from falling but they wouldn’t stop. My trembling voice infuriated me. I wanted to care less, to be as unaffected as she seemed by what had happened. “Well, I hate you, too,” she replied. Her voice trembled not at all – she was cold and matter-of-fact, the Ice Queen. “So now we both know.”

My stomach tipped. Could this be happening? There was a silence between us. I looked at her. Nothing. No love in her face. There was nothing more to say. “End of scene,” called the person reading the stage directions.

The room erupted into laughter as my mother and I both cried out, “I’m sorry!” and fell into a hug and rocked each other back and forth. She kissed my cheek and I kissed the top of her head. She tipped her head so our foreheads were touching and whispered in a silly voice: “I don’t hate you, I love you sooooooooo much!”

We were in a rehearsal room on Theatre Row. It was the mid-Eighties, and I was 25 or so. My mother and I sat back down in the audience next to each other and held hands, my mother’s thumb rubbing on the back of mine, as Ron, the moderator of the playwright’s group, turned to the playwright. “So, Stephanie, is there anything specific you’d like to know?”

I remember now that, as I fell asleep that night, I kept flashing back to the way my mother had looked at me when she said that she hated me – how dismissed, beside the point, I’d suddenly become. Where had her love for me gone while she was pretending, so well, not to feel it?

I'm still not able to grasp that this time is different. There have been so many performances over the years. I can’t wrap my brain around the idea that I’m the only one here who is doing an improv; I’m the only one who can step out of the scene. My mother is living awake in the actor’s nightmare.

My mother is living awake in the actor’s nightmare. But she is far braver than i have ever been. She's game. She never lets on, never drops character

But she is far braver than I have ever been. She meets it fearlessly. She’s game. She never lets on, never drops character. She soldiers on, no matter what. She is in the moment; that’s all that exists for her now. I imagine someone calling, “Blackout!”, the lights going out, and then my mother, unable to leave the stage, alone, blinking into the dark.

It’s early summer of 1976. I’m 14. I’m sitting in a theatre, on a blue faux-velvet seat, watching the rest of the audience settling in. I flip through the playbill and read the actor bios, stopping every once in a while and checking to see if I can make out any movement behind the curtain as chairs squeak and papers rustle and people speak in low murmurs and coughs. I arrived at this small coastal town earlier today to join my mother for a few weeks as she tours in the play I’m about to see. She’s been touring already for two weeks, and will continue for another two weeks after I leave.

The theatre is full. My mother is the third lead. The other two leads are a well-known married actor couple – Anne Jackson and Eli Wallach – whose names go above the play’s title in the posters (my mother’s name appears below the title, although her agent managed to secure her an “And” before her name, and little box around it). I know that the rest of the audience is here to see the well-known actors, but I feel that familiar secret pride of knowing that they will also be watching my mother.

The house lights go down, and the curtain and stage lights come up revealing Eli Wallach alone on stage. There’s a sustained round of applause, and another when Anne Jackson appears. In the play, they are not married, but are having an affair.

The play turns out to be a comedy, slightly absurdist and intentionally improbable, about average people with big dreams; the set is the man’s New York basement apartment. The audience loves watching the husband and wife working together and laughs immoderately and fondly. My mother is nowhere to be seen. I like this feeling of anxiety mixed with excitement as I wait for her: I understand the phrase “on tenderhooks” as I strain to see if she’s about to make her entrance

Suddenly, I notice that the door to the bedroom is open, and that someone is standing there. It is, finally, my mother. She’s wearing a pink bathrobe and furry slippers, and she looks small, scared, slightly feral, and, I think, adorable. She watches the other two characters for a few minutes, then closes the door, disappearing.

When she appears again and begins interacting with the other characters, three things become clear: she is the man’s wife, she doesn’t want him to leave her, and she is suffering from some kind of mental dysfunction that makes her non-sensical. She tries to cook Brillo pads for hamburgers; she refuses to leave the house because her fingernails are all different lengths.

She is brilliant in the role.

My mother keeps a tight hold on herself in real life, so maybe the release the character offers has tapped into something – some madness, some irrationality and impulsiveness – she doesn’t usually allow herself to feel, let alone show. She blends so completely into the character that it seems the woman I think of as my mother has been consumed by this sad, funny, needy, crafty, demented, vulnerable, brave little person with her huge Keane eyes and her loony-tunes speeches. She is the surprise of the evening, and the audience hangs on her words, follows her with their eyes as she darts around the stage. I’m no less transfixed. I, too, am in love.

And I am, just like that, motherless. The vague feeling of separation, of being in limbo, untethered and unclaimed, that’s endemic to seeing my mother on stage is magnified by her complete disappearance into this character. The stage has always removed her from me; this time, it seems to have gone so far as to replace her. Even though I know better, I wonder, will she be able to come back when the play is over?

At intermission, I hear people talking about her in awe-struck tones. I’m agitated as the second act begins, and then as the plot works its way to the climax – the husband’s big break – and then to the denouement – his failure, and the loss of his girlfriend to another, more successful man. We, in the audience, ache for him. His dreams have all come to nothing.

He and my mother are alone on stage, and she’s trying to cheer him up. The lights are so low that the audience can barely see what’s happening. He doesn’t respond at first, but then he turns to her. I watch as he walks over to my mother, takes her face tenderly in his hands, and kisses her gently on the mouth. She responds, and the kiss becomes deeper and more passionate. His hands move down to her throat. My mother starts, and I suddenly realise he is choking her. The audience gasps. She struggles, her hands trying to push him away, but he is inexorable, and they sink together to the floor, my mother under him, him above her in what could be lovemaking, but isn’t, and then she stops moving, and so does he. After a moment, he gets up and leaves the stage. The audience is silent, and I’m desperate to contain the sound of my crying. I’m shaking, soaked, my nose running; no one told me to bring tissues.

As soon as the curtain calls are done, which takes what feels like forever because of all the standing ovations, and the house lights come up, I run backstage. I have to wait in the green room until she comes out, traces of stage make-up still on her eye-lids and along her hairline. I hug her so hard I’m afraid I might hurt her, but she says it’s OK. I’m still crying, and laughing at myself for crying, and she, understanding, rocks me back and forth, and kisses my forehead. I pull back and look at her, wiping my nose with the back of my hand.

“Are you, you?” I ask, pretending, even to myself, to joke. She laughs. “I’m me.”

“Are you OK?”

“I’m fine, darling.” She moves my hair out of my eyes and strokes away the tears that are still there.

“I think you were too good.” I say. “Jesus.”

Mom checks out with the stage manager and gets her call time for the next day while I tell all the other actors who are now coming into the green room how amazing they were, and we all laugh at my crying so much. Eli kisses my cheek, and Anne gives me a hug. Then Mom hooks her arm through mine, and we leave the theatre.

Maybe the truth is that I’m the one who’s still on stage, refusing to believe that the play is over. I am Negating real life, insisting it be a performance. Drop the act, Mom, I want to say. Put your street clothes on; leave the costume in the dressing room – it’s so effective, really, with all those mismatched, oversized pastel-coloured clothes, yikes!

Put on your Sonia Rykiel sweater and black gabardine pants; kick off those clunky sneakers and tube socks and slip into your patent pumps. A little lipstick, a little blush and liner; turn your head upside down when you brush to loosen the spray that has made your hair lie so flat. Let’s go have dinner. Come on. I want to pull her out through her eyes, I can see her in there, and make her leave this character behind, a shell in a wheel chair ...

Or, if this is an actor’s nightmare, can someone please, please wake me up?

Sometimes when no one else is in the house, I call her. I call guiltily, in secret, a secret vice, calling her just to get a scraping, the self-medicating lie that we are having a conversation, that this is at all my mother. Her voice goes directly in, like honey, and I sink down into it, into home, a mockery of itself, and yet itself.

“Hi, Mama,” I say when she answers. “It’s me, Katie. Katie.”

This article was a collaboration with The Iowa Review https://iowareview.org. Kate Neuman is a writer and actor based in New York. “Yes, And.” is adapted from a memoir-in-progress. Visit kateneuman.com to see more of her work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments