Should we consider AI art to be true art?

Art generated by AI is the latest internet trend – but it is already having major ramifications for the creative industries, writes David Barnett

When artist Dave McKean first learned about art generated by artificial intelligence (AI), his knee-jerk reaction was: “Well, that’s my career over.”

The images, actually created using very sophisticated recognition and rendering engines, have become the latest trend. And that worries McKean, a multimedia artist who utilises painting, drawing, digital techniques and more for book illustration, album covers, comic books, photography, in a multi-discipline career that began before he left Berkshire College of Art in 1986.

He has illustrated the covers for every issue of the Sandman comics for DC, and brought his talents to the animated end-credit sequences of Netflix’s recent adaptation of the comics written by Neil Gaiman, a long-time collaborator of McKean’s.

He’s already at the cutting edge of digital processes in his art. But he could see that the rise of AI art was something very new, very different.

AI art, on platforms such as the hugely popular Midjourney and Lensa, allows users to simply type in a prompt for the image they want, and the AI engine creates it for them in seconds. That’s the simple version.

“I started to see images on a few of my illustrator friend’s Facebook feeds that were confusing to me,” says McKean, “so I looked into the way AI-generated imagery worked and then spent a day on the floor of my studio in a foetal position.

“It took no more than a few minutes to understand the principle, and then the implications, of deep-learning, and then a quick look through the endless galleries of end results to see the power of it, and my immediate response was, well, that’s my career over. Why would anyone pay me to do an album cover, when anyone can type a few words into [a programme] and in a couple of minutes start downloading endless finished possibilities, for free?”

But how does AI actually create its art? In the most simplistic terms, it trawls the entire internet to find “bits” of existing artwork to put together for the image you have asked for. But it’s a lot more complex than that – what McKean calls “deep learning”. He says: “It doesn’t cut and paste existing imagery, it understands the nature of what you are asking for, ‘deep learns’ for example, the nature – colour, shape, scale, texture, reflectivity – of a banana, and then it can render a completely new original banana for you. If you ask for a stone banana, it deep learns the nature of stone, and then applies that to the nature of banana – voila, a stone banana. When you start typing more esoteric, emotional, abstract, contradictory words in, it tries to resolve all this direction in one image, and the results, because it’s drawing on such a near infinite data set of posted online imagery, are often genuinely surprising.”

Tom Abba is the director of the University of the West of England’s Digital Cultures Research Centre in Bristol, and he too has been keeping a close eye on AI – and uses the example of a carrot, to McKean’s banana, to explain how it works. He says: “The engine is ‘trained’ on a body of work that’s identified across the web. That’s examined and cross-indexed with meta tags, descriptions and other ancillary material such that an AI engine can ‘recognise’ that a picture of a carrot is a ‘carrot’.

“The machine can then respond to a ‘prompt’ to generate a ‘stone carrot’, for example. It understands what a carrot looks like and knows what stone texture is, so it combines the two. That’s the essence of it – the application through more complex prompts and configuration is what’s been happening since the summer. The engine is also evolving, in that it’s getting better at understanding ‘carrots’ and ‘stone’ and is returning better quality results.”

You may well have seen people posting on social media the results of their AI experimentation, and they are astonishingly good. And that’s what rang major alarm bells for McKean. “In an already oversaturated media/internet landscape it felt like everything became suddenly meaningless. Everything became a pixel in a kind of median beige infinite gallery of noise," he says.

“In a world where already most of the power has been moved from the artists to the marketing departments, where grey people demand 50 finished roughs for everything because they don’t know what they want until they see it, AI is their wet dream. So even though the sugar rush, technically astonishing tsunami of it was overwhelming and exciting, I immediately felt a sense of drowning in this brave new world.”

The commercial ramifications of AI art are already out there. Need a book cover or an illustration for an album? Why pay an illustrator to produce it, which might take months, when you can do it in seconds, for free?

“It’s done already,” says McKean “The commercial media world is largely about getting to an end result, on budget and deadline... Obviously, that world will embrace AI as the ultimate delivery system in a capitalist world. Any technical limitations and cliches we’re already starting to see in this new tool will be ironed out in future iterations. We’re only a few months into it and look at what it has achieved already. AI will affect every aspect of our lives, and is already being brilliantly employed by scientists needing huge data sets and number crunching, think virus detection and vaccine creation."

“It’s surprised me how fast and how well AI has pushed its way into the creative areas of our lives,” he adds. “It’s strange to me that anyone would want to read AI poetry, listen to AI music, or look at AI imagery, when we already have hundreds, thousands of years of astounding human activity in these areas, every single one of which is a window into an actual human life and context," he says.

“The argument that it’s a democratisation of creativity seems to me to be completely bogus. On the one hand, creativity is already entirely democratic – anyone can have a crack at drawing something, playing piano, writing a story, you don’t need anyone’s permission or membership of a secret club, just get one with it and enjoy the doing of it. Also, typing a word into a bot and letting it make a picture for you is not any definition of ‘creativity’ I recognise. It has as much to do with playing the piano as just putting on a record of someone else playing the piano.”

Abba agrees the ramifications for the art world are serious. “There seems to me a real danger that a whole tranche of illustrators and designers will find their work drying up very quickly,” he says. “Nobody in their right mind really thinks that an overstretched art director is going to fork out for an illustrator when a desktop tool can produce apparently usable results. Capitalism simply doesn’t work like that. Book covers, album art, pre-production design for film, TV and theatre will all be impacted.”

However, McKean isn’t just raging at progress here. After his initial reactions at AI art, he decided to push those feelings into action. He says: “I decided I could either quit or respond. The whole subject filled my head, I couldn’t think or talk about anything else, I had to do something with all that energy. I make things, I tell stories, I think in comics, so I immediately decided to make a book of three exercises, to demonstrate the power of it, to see where its strengths and weaknesses lie, to try and get a sense of how the algorithms work, and what their prejudices are.

“And to work through all the questions I kept asking myself about why this was happening, where did I fit in, if at all, how AI thinks, and what now are the working definitions of art, creativity and intelligence?”

McKean had already been thinking about a project based around the epic of Gilgamesh, the hero of Mesopotamian mythology. It seemed too good an opportunity to pass up. He says: “It seemed interesting to me to feed humanity’s oldest known story, created thousands of years ago by anonymous minds, two lines at a time back into the vast anonymous hive mind of AI, aim it towards stone relief carving to mimic the almost impenetrable cuneiform tablets that originally held that story, to see if anything of the narrative could survive that journey.

“I didn’t print the text, I wanted to see if anyone could intuit what was going on just from AI’s interpretations of the text. Part two took a headline a day from a newspaper and fed that neutral text into AI to try and get a sense of how it sees us.”

As part of the project he began a conversation with the AI engine, feeding in his own musings as he walked around Rye, and questions about it, and asking it what it thought it had learned from the Gilgamesh project.

He says: “All this imagery, my photos and the AI answers were then fed through another AI process, sampling the textures of my own painting and applying them to everything, so it all started to have a similar feel, and the boundary between the AI world and the real world started to break down. That mirrored exactly how I was feeling at the time.”

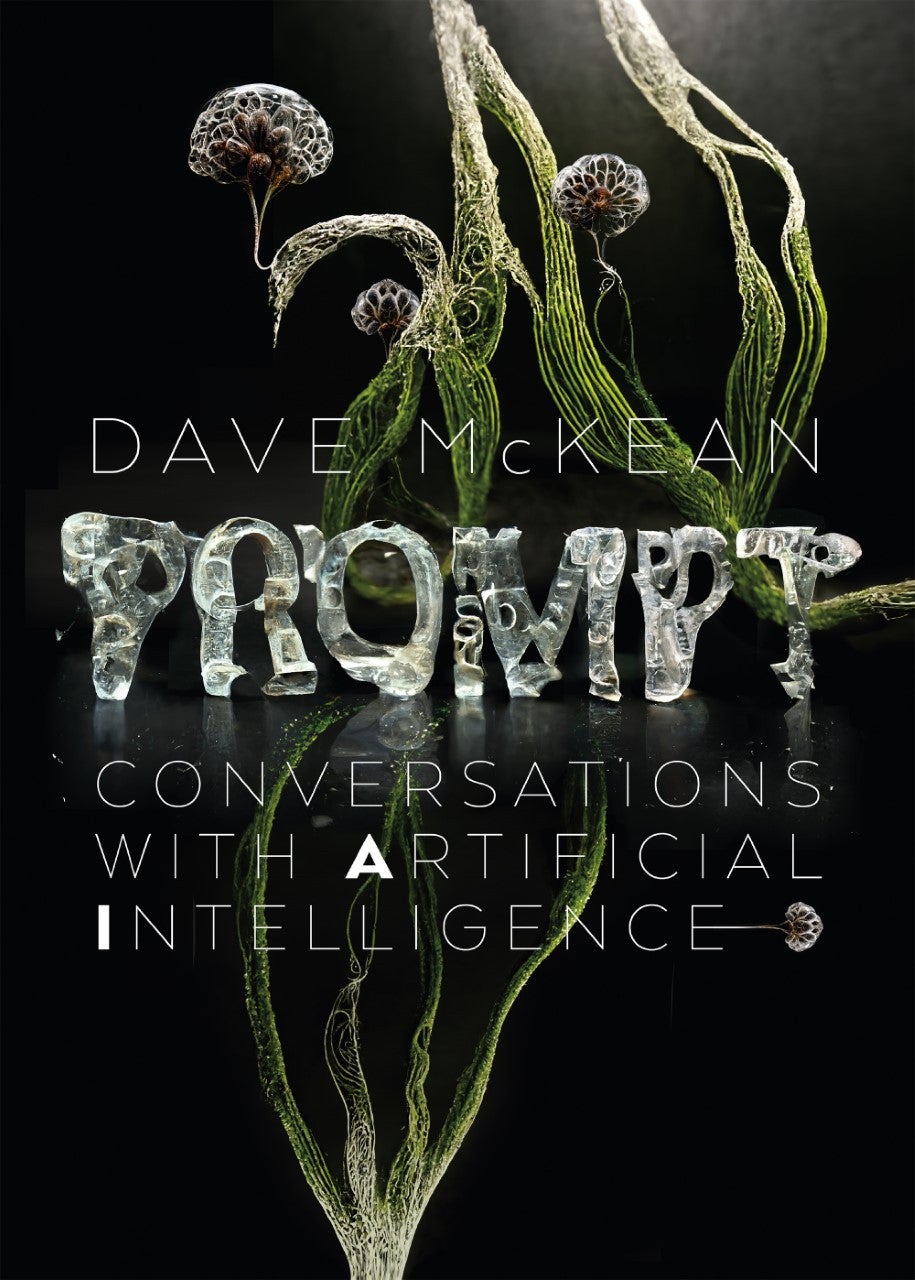

The end result is a 96-page illustrated book titled Prompt: Conversations with Artificial Intelligence, weaving in the Gilgamesh story with McKean’s own personal journey of discovery with AI. But ultimately, and notwithstanding the commercial applications of it, is it art?

McKean says: “This is not only a complete resetting of the idea of what creativity is, it also comes with a need for the law to understand what’s going on, and adjust and update its definitions of intellectual property rights and infringement appropriately. It’s going to be very difficult to put any of this Pandora’s Box of forces back into anything that looks like a framework that will safely allow creators to work at the jobs they used to have. That may be the price paid.

“My argument is that the end result is not where the ‘art’ is. It’s the journey that matters, not really the destination. I used the structure of a walk for my book for a reason – the AI equivalent of going for a walk from A to B is to just teleport to B. But that achieves nothing of what you want from a walk, it doesn’t get your heart rate up, and fresh air in your lungs, it doesn’t allow you to watch the world turn, the seasons change, to be surprised by the things you see, or the other pathways that you didn’t know you wanted to try when you started. The walk is all about the journey, not just the destination.”

For Tom Abba, while everyone is having fun playing with AI art generators, there are some very weighty questions stacking up that will have to be tackled. “For me, at least, the questions about ethics, originality and the purpose of art aren’t being addressed," he says. “This is also happening very, very fast. Engines are updated frequently, and the questions about who owns this stuff aren’t (yet) being asked properly. Who has the copyright on a piece of AI art? The machine, the prompter, the artist who (unwittingly) supplied the images?”

The last word must go to McKean, who after almost 40 years of working as a professional artist is facing what he believes is an existential threat that he could not have even considered in his wildest fantasies when starting out.

“At the end of the day, after making thousands of images using AI and looking at thousands made by others, my feeling is that what I personally love about art and creativity is not there,” he says. “It makes hugely facile, complex, surprising and chaotic stuff, but the internet’s full of that already. What I love about art is the sense of seeing the world through the eyes and mind of another person, to experience their lived stories, empathy.

“If AI is to contribute to this, it will have to be folded into the process of a human for me to feel anything. Art remains for me, by definition, a human pursuit. In the coming decades, I’ll see if anyone else agrees with me.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks