When the boundaries melted away: why 1994 was music’s finest year

A quarter of a century ago, music had its finest ever year. Come at me, says David Barnett

There will be those who have just read the headline and already gone directly to the comments to take issue. For any waverers, I’ll set out my stall again: 1994 was the best year in music. Possibly ever. Still here? Right, we happy few, let’s unpack this a little. Putting the words “best” and “music” together is always going to be subjective. One woman’s Metallica is another man’s Joe Dolce. And there’s also time and place to take into account. If you were six years old in 1994, you might not have been bothered about contemporary pop. If you were 76, maybe ditto. But there are certain immutable, irrefutable truths, and this is one of them. The year 1994 was spectacular for music on so, so many levels.

Perhaps a bit of wider context is needed. To live through 1994 as a relatively young person (I turned 24 in the January) was to be at the centre of what felt like a time of transcendent change in the UK.

That was the year the IRA ceasefire was signed, and 9/11 was still seven years away, and not on on our radar at all. After the breakup of the Soviet Union three years earlier, Russia was more interested in implementing democracy and capitalism than fighting a Cold War. It felt like the dawn of an age – sadly short-lived – when nobody was trying to blow us up.

In 1994, Bill Clinton was in the White House, and still a year away from staining his character (and a dress) by not having sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. Neil Kinnock’s Labour had somehow lost the 1992 general election, despite everyone being confident the Tory stranglehold was finally over, but in 1994 Labour named Tony Blair as leader of the party, and things... well, things could only get better.

To live through 1994 as a relatively young person ... was to be at the centre of what felt like a time of transcendent change in the UK

After what seemed like years of stagnation, there was a whiff of change in the air. Things felt in some way more optimistic. The country felt more inclusive, less divisive. There was opportunity, and expectation. It was the year they launched the National Lottery. Any one of us could become a multimillionaire by buying a ticket for a quid.

And music reflected this, as it always reflects the world around it. There was a sensation of rapid, almost out-of-control evolution in music. People’s record collections became more eclectic, more wide-ranging, more small-c catholic. The old boundaries seemed to melt away. You didn’t need to choose between being a rocker or a raver or an indie-kid or a popster. You could be all of them at once, because if the bands and artists were refusing to stay in their pigeonholes, why should the public?

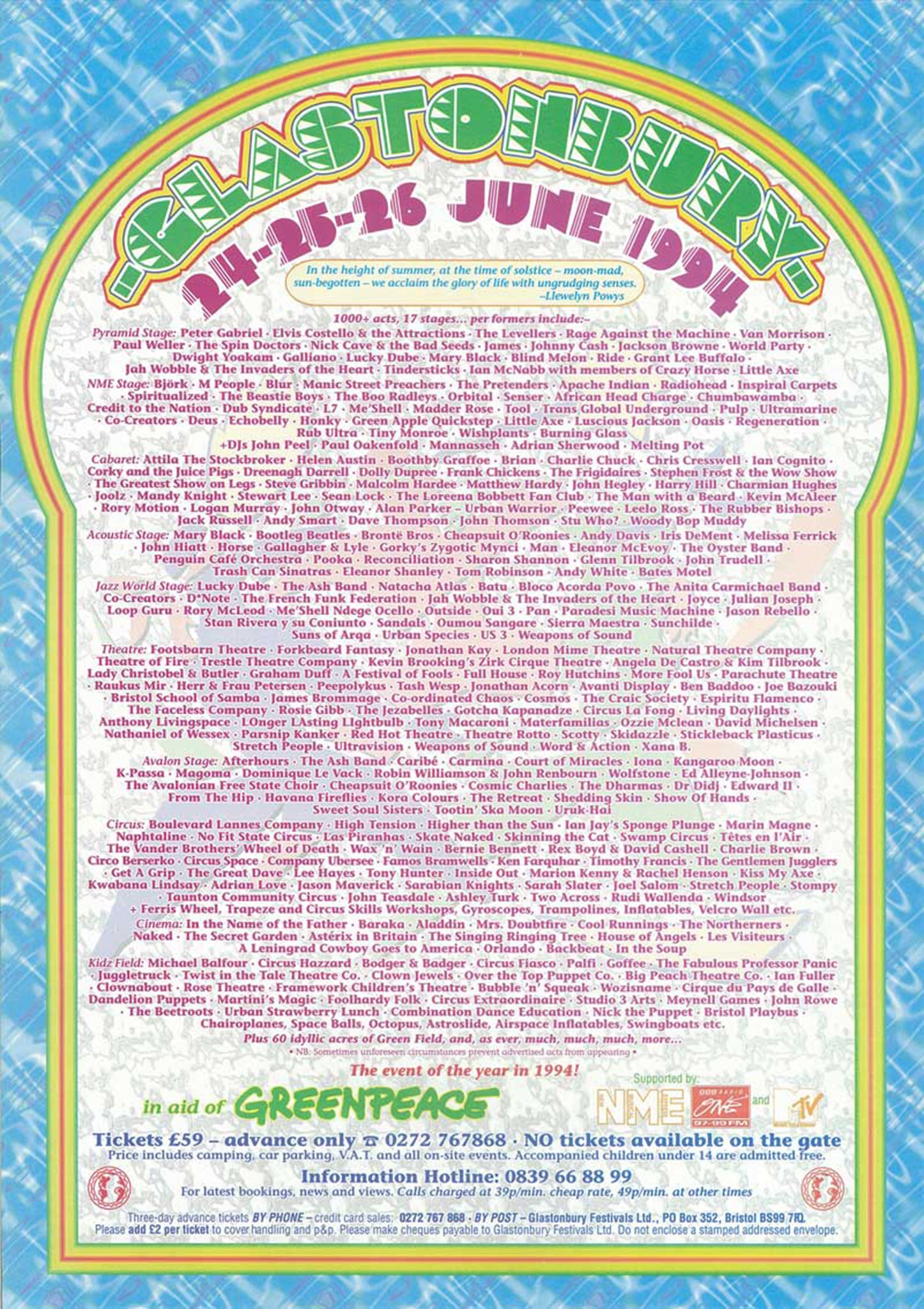

Slap bang in the middle of the year, at the Glastonbury Festival at the end of June, I stood in a field and had a transformative experience watching the progressive techno band Orbital playing a set to what felt like half the people in the world. They had come to Glastonbury to see Oasis, or Rage Against the Machine; they had come for Björk and James. They had come to listen to Nick Cave, to jump around to Blur, to dance to M People. And in the end, they all came to watch Orbital playing their bleepy, unnerving, bass-pounding music of the spheres, and for what felt like the first time ever the tribes were all united in the love of music.

Of course, that could just be the drugs talking. But look at that Glastonbury line-up! Just one year, one scorching hot June weekend! And you can add to that list St Etienne, Paul Weller, Pulp, Spirtualised, Radiohead... possibly the best Glastonbury ever, in the year of the best music ever?

That coming together at the Orbital set heralded a sea change for Glastonbury. According to Sheryl Garratt’s excellent book detailing the rise of rave culture, Adventures in Wonderland, Glasto organiser Michael Eavis had previously shied away from having a dance stage because of the negative connotations attached to rave and techno – primarily the drugs, illegal events and mass takeovers at places like Castlemorton two years previously.

She wrote: “But after Orbital’s live set stole the show in 1994, a dance stage and dance tents were finally introduced the following year, and Glastonbury has become an annual event on the club calendar.”

If I had to fight with myself over this bold claim for 1994 to be music’s finest year, I’d probably employ maybe 1988 as my weapon of choice. That was really the start of rave culture, and where dance music began to cross over with guitar bands, resulting in the baggy Madchester sound epitomised by the Happy Mondays, the Stone Roses, James and the Inspiral Carpets.

But while that might have been where the seeds of fusion of the genres and inclusivity were sown, I’d argue that it wasn’t until 1994 that those ideas and concepts properly blossomed. And, of course, 1994 was the year of Britpop.

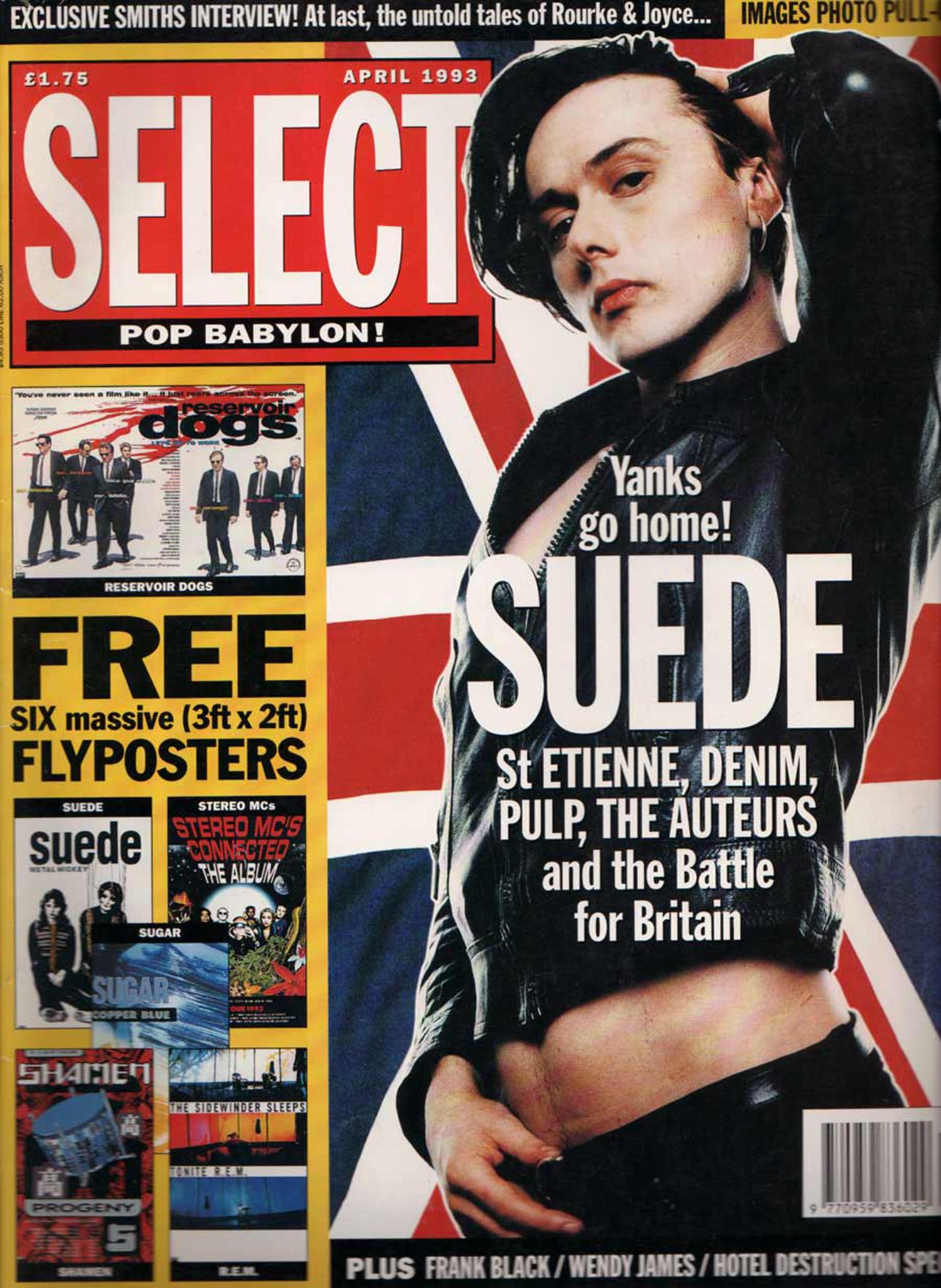

It was actually in 1993 that Britpop got going, thanks to a feature in the now defunct music magazine Select. Grunge, with its poster boys Nirvana and their lead singer Kurt Cobain (more of whom anon) had held sway with its nihilistic, fuzzy guitars in Britain for a couple of years among an army of plaid-wearing, chain-smoking disaffected youth. But Select wanted to wave the flag for Blighty, quite literally as that month’s issue featured on its cover Suede’s Brett Anderson against a union jack background and an article inside headlined, “Who Do You Think You Are Kidding, Mr Cobain?”. Denim, Pulp, Suede, The Auteurs and St Etienne were all featured, in a bid to push British pop back up the agenda.

By 1994, two seminal Britpop albums went head to head – as did the bands responsible for them. Oasis released their debut Definitely Maybe, while Blur brought out their third LP, Parklife. Oasis v Blur bubbled under throughout the year, battle lines drawn at the Watford Gap. It was the naughty north vs the sexy south, Manchester’s Oasis and their Beatlesque anthems set against Blur’s cheeky chappy Camden Kinks roisterers. By the following year, the so-called rivalry even made the BBC evening news as the two bands released singles on the same day.

If there ever was any proper animosity between Oasis and Blur, it didn’t extend to the fans. Blur or Oasis might have been a perennial pub debate throughout 1994, but I don’t think I knew anyone who didn’t own both Definitely Maybe and Parklife. The rivalry added a bit of spice, and music fans were the winners with two defining albums of the decade.

Britpop wasn’t only about Blur and Oasis, of course, though as the cocky lads in the class they tended to get most of the attention. But let us consider some of the other releases that came under the red-white-and-blue Britpop banner: Pulp’s His ’n’ Hers, considered to be the album that brought them to mainstream attention, especially for the standout tracks “Do You Remember the First Time?” and “Babies”; Echobelly’s debut Everyone’s Got One, with its spiky, caustic, feminist songs; Suede’s second album Dog Man Star, which perhaps exemplified how bands were not afraid to evolve and transform in 1994. Suede’s first album was almost a paean to Bowie with a side order of The Smiths; here they’d gone much more personal and perhaps introspective.

Another band that completely reinvented itself in 1994 was Primal Scream. Never a band to stick with one musical style, they had, however, found a niche in the dance-rock mash-ups of 1991’s Screamadelica. When they returned in ’94 with Give Out But Don’t Give Up, it could not have been further from the blissed-out rhythms of “Loaded” and “Higher Than the Sun”. The Scream had gone full-on Rolling Stones blues, and the first single from the album, “Rocks”, was the band’s highest-charting release.

Had 1994 given us only Britpop, the year would still have deserved a place in posterity. But it was about so much more than that. Select magazine might have jokingly tried to drive America back into the sea the previous year, but US bands released some absolutely classic albums that year.

What about Green Day’s Dookie, and its single “Basket Case”? By 1994, REM were stone-cold alt-rock royalty, and while their ninth studio album Monster might not be in everyone’s top five REM albums, it did at least give us the single “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?”. Weezer released their self-titled debut, and Beck gave us the unalloyed eclectic joy of Mellow Gold and the single “Loser”.

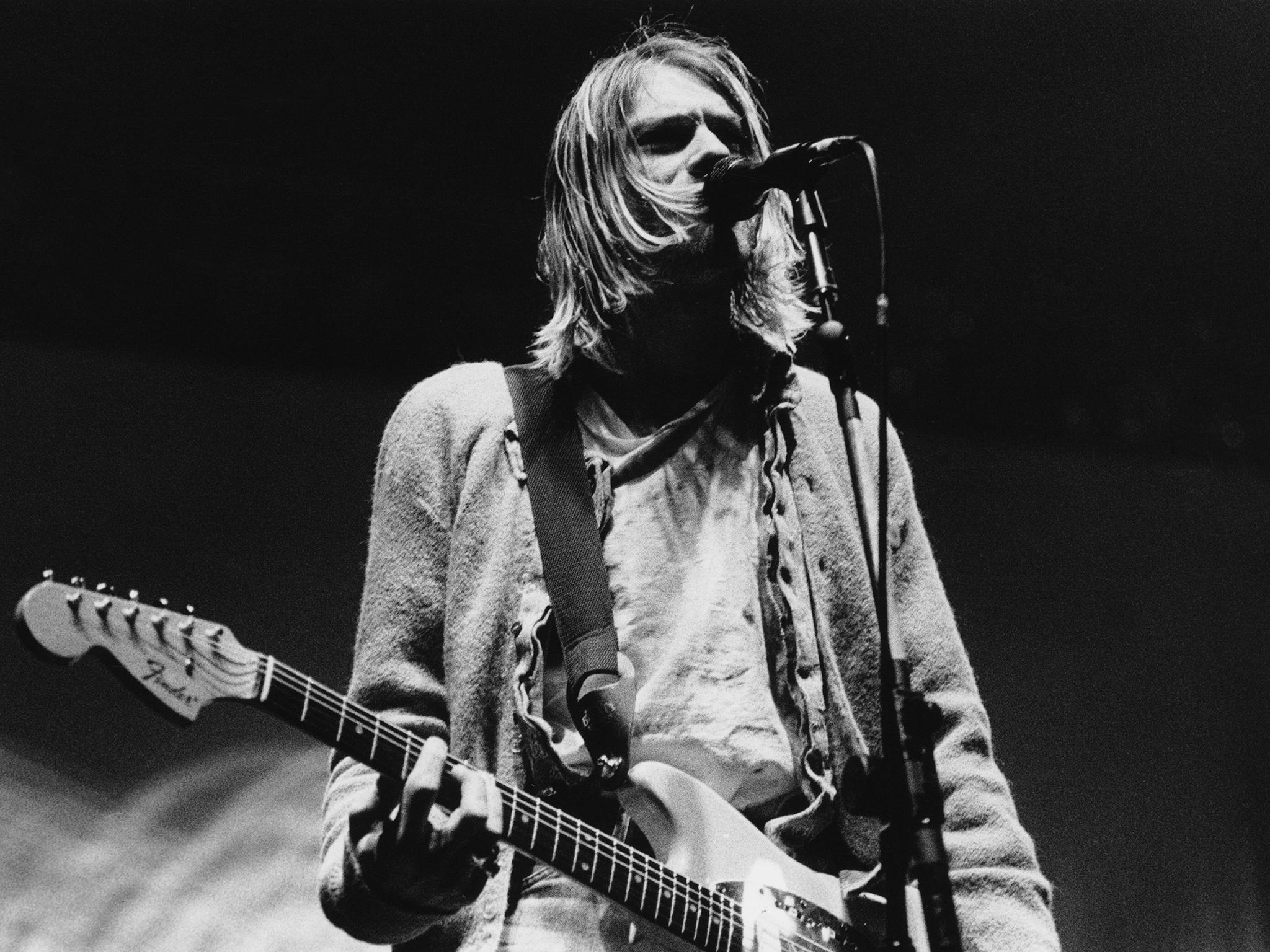

But the most influential American band of the era, Nirvana, came to a tragic end when, in April, leader Kurt Cobain wrote a note to his imaginary childhood friend and then put a shotgun to his chin and pulled the trigger. He had gone and joined that stupid club, the one where the most talented musicians of a generation end their own lives at the age of 27. Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison. The year had its martyr.

This was also the year that music fans who’d previously filled their CD racks with white boys playing guitars began to embrace rap and hip-hop – and also when hip-hop transformed, Kafka-like, into something quite new.

Then Notorious BIG released his debut Ready to Die, and indeed he did, becoming the martyr of 1997 a few years later. Public Enemy brought out their highly acclaimed fifth studio album, Muse Sick-n-Hour Mess Age, and the Beastie Boys fused hip hop with the greatest 1970s police detective show that never was with the video to their single “Sabotage”.

In Britain, this acceptance of rap into the music collections of the largely white indie-kid audience led to the birth of something else we can thank 1994 for: trip-hop.

The term was coined that year by a Mixmag journalist to describe the bass-heavy fusion of hip-hop and dance music that was largely coming out of Bristol. Massive Attack had already released the seminal Blue Lines album and the evergreen “Unfinished Sympathy” in 1991, but this year saw their second album Protection, and its standout single release “Karmacoma”. But the year was most notable for Portishead’s debut, Dummy, drenched in blue and heartbreak, and the soundtrack to a thousand all-back-to-mine post-club chillouts.

What else? Well, we could still get away with forgiving Morrissey a lot back in 1994, especially with his fourth solo album Vauxhall and I. The Manic Street Preachers released The Holy Bible, the last work to feature troubled lyricist and guitarist Richey Edwards. The following year he would go missing, never to be found, making a martyr of a more introspective kind than Cobain’s dramatic exit. The old-stagers were keeping on keeping on, with albums from Madonna and the Rolling Stones, and even a wealth of previously unheard Beatles material from their sessions at the BBC.

But if there was one comeback that exemplified 1994, it had to be The Stone Roses. Their self-titled debut album in 1989 soundtracked a generation. Their return five years later had a lot riding on it in terms of expectations. So, of course, they titled it The Second Coming.

Was it ever going to be as good as The Stone Roses? No, of course not, because that album was perfection. But with singles such as “Love Spreads” and “Ten Storey Love Song”, they made a pretty good fist of it. But it was an event, it was exciting, it was history-making. And it was brave and reckless and so typically Stone Roses to release their first new album for years when everyone had all but written them off, and especially to do that in the greatest year for music ever.

Without the benefit of the internet or smartphones, we discovered new music in 1994, we heard it in the pubs and at gigs and in clubs and festivals and on John Peel’s radio show. We bought indie music then we went to Creamfields or to superclubs in places like Leeds, and danced until dawn.

Techno got hard and heavy. The aforementioned Orbital released Snivilisation, a growling, science-fiction nightmare of an album. The government tried to kill off rave culture good and proper with the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, which drove people into the clubs but also earned a response from the Prodigy in the form of Music for the Jilted Generation, a howling, psychopathic protest album that gifted us the insane energy of “No Good (Start the Dance)” and “Voodoo People”. The Chemical Brothers, under the name the Dust Brothers, started releasing singles. Dance music became raw and scary, a self-fulfilling prophecy for those in positions of authority that thought they simply had to ban it.

Music in 1994 was a diverse mess, just like it always is. But it seemed as if there was an invisible thread running through all these genres that connected people through a general love of music. You might love Oasis more than the Prodigy, or Blur more than Portishead, but the chances are you listened to all of it. The year was about invention, about reinvention, about throwing open the doors and just trying everything. It was involving and inclusive and seems to shine so very brightly from the vantage point of today.

The obvious answer to all this is that I am just old and clinging on to a year that seemed glorious just because I was there. But I insist: 1994 was the best year ever for music, and its spirit is something we could sorely do with today. Come at me.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks