Mormon, stripper, survivor: the tragic and triumphant life of Margaret Dupre

In 1977 a single mum of three left her home in Essex, bound for a new life in Australia. On arrival in Pinjarra, her kids were seized and forced into hard labour on a farm and she was sent to Perth. To survive she became a stripper and later a national pin-up girl. Years later and reunited with her daughter in Los Angeles, Andy Martin hears their heartbreaking story

At the tail-end of the sixties, my old friend Jonathan, in a spirit of youthful naiveté and optimism, took ship for Australia. He had been spun a tale of golden beaches, perpetual sunshine, ice-cold lager on tap, and a life of boundless pleasures. A never-ending holiday. And it only cost £10 (on the subsidised migration scheme). So off he went. As soon as he landed, in Perth, the Australian government kindly informed him that he wouldn’t have to go far from the harbour because he was getting on the next ship to Vietnam, where, as a “naturalised” Australian citizen of fighting age in excellent health, he would soon be getting stuck into some steamy jungle warfare. Heaven, in the month or so it had taken him to sail there, had turned into hell. Jonathan wisely did a runner and went underground – quite literally, since he took a job as a miner for a few months. So far as I know he is still a fugitive from Australian justice.

Margaret Dupré was like Jonathan – more than a little disappointed by her reception in the Promised Land. The old “false prospectus” routine. Her solution was something like the opposite though: she took to hiding in plain sight, going for maximum exposure, on the beach, as per the original propaganda. While Jonathan was hacking at a coalface all day long, she took her clothes off for a living. I am now going to ditch Jonathan and concentrate on the story of Margaret instead. Partly because her daughter, India, has made a short film about their adventures together, called Stripped.

India was the reason they even went to Australia in the first place. Margaret was a young mother of three, living in darkest Essex. A single mother, who had converted to Mormonism. She didn’t smoke and she didn’t drink. She was now aged 27. And India had asthma. A doctor suggested the Australian climate would suit her better. Margaret was offered a job as a teacher by the benevolent Fairbridge Society and so, in February 1977, they all flew down under: Margaret Dupré, India, aged 4, and her brother (9) and sister (3), full of hopes and dreams of a new life in the sun, inspired by black-and-white government films of children having fun and games, snatches of Waltzing Matilda, kangaroos and koalas, and the words of the Dorothea Mackellar poem, “I love a sunburnt country”.

“I suppose, looking back on it, ” said India, in Los Angeles, “we were naive. ” I met India when she took me to a Hollywood hospital to meet Margaret, who was lying in bed with various wires attached to her, clocking her heartbeat. She is still ticking, fortunately. She is becoming an American citizen this month. But she will never forget Australia.

Back in 1977, the wonderful Fairbridge Society (or “Society for the Furtherance of Child Emigration to the Colonies”) people were there to welcome them all on Australian soil, as per the deal. Almost nothing else, however, was quite as described. The “Vision Splendid” in the words of founder Kingsley Fairbridge was nothing more than a “ruse”, a “trick”. They were “lured over”, said India. The job, for example. That went straight out of the window. They just ripped up the contract. Took the letter of employment and tore it in two. Offer rescinded.

Meanwhile, Margaret and India and her siblings were now committed to spending at least two years in Australia. She knew no one in the entire country. And she had no network to appeal to back in England either. “That was something they checked on carefully, beforehand,” said India. “They wanted you to be white, of course. They were afraid of an Asian invasion and wanted to create an all-white Australia.” There was, in fact, a policy known baldly as the “White Australia Policy” – blacks need not apply. “Then you had to be interviewed and they would make sure you didn’t have a support system. So you’d be all on your own and completely powerless.”

Which is exactly what they were. They had been told they would have a “cottage” together. In reality the kids were sent to “farm school” while the mother was forcibly packed off on a bus into the city. India remembers chasing the bus down the street. Australia had a bad habit of splitting up parents and children. The aboriginal children who have become known as “the stolen generations” were forcibly removed from their biological parents and re-located with white families. But something similar could happen to white children too. It was no longer legal to ship children from Britain to Australia, as had been the case after the war. Bringing over single parents with their kids was the next best option. It was not dissimilar to the Irish “Magdalene Laundries” system for “fallen women”.

The Fairbridge “Farm school” was a work camp by another name, in Pinjarra, way out in the outback (so much for all those beguiling images of beaches). It was closed in 1981, and the Australian government would eventually apologise for dumping children in orphanages where they were likely to be abused.

But back in the seventies, the Dupré kids were, in effect, slaves of the system. They worked up to 16 hours a day, digging, scrubbing, chopping wood, from before dawn until after dusk. “It was one of the coldest places you could imagine,” India said, “even when it was hot. There was no love, no sense of any warmth. You weren’t allowed to express any personality. You couldn’t wear shoes either, so you wouldn’t run away. They gave you trousers with the pockets sewn up so you couldn’t put your hands in your pockets.” They were allowed a shower once every couple of weeks, to save water. “You were treated like the scum of England – you were told, ‘You are the scum of England that no one wants’. ”

For all these great “opportunities”, according to deeply condescending letters that passed between authorities in Australia and England, they were supposed to be “grateful”. They didn’t feel grateful though. They were missing their mother too much at the time. Meanwhile, in Perth, unemployment was rampant. There were no jobs going. When Margaret saw a sign on a marquee saying STRIPPER COMPETITION. $100 FIRST PRIZE, she said to herself, “I can’t possibly do this – I’m a Mormon! ” On the other hand, she had to get some money together to have a hope of getting her children back. So she went in. And was promptly rebuffed. “You’re not the type,” says the main man, in his blunt Australian way.

It was like throwing down a gauntlet. A serious moment of existential crisis and self-reinvention. Just as the playwright Jean Genet in Paris once chose to be a thief and a queer to defy society, so Margaret Dupré in Perth chose to make herself into a stripper. She had been a shy Mormon, who loved art and playing with her kids, still child-like herself. Now she was a brazen stripper. “It was her transformation,” said India.

Margaret found some clothes in a lost-and-found bin, cut them up, and created some kind of Hiawatha look. And she put on make-up for the first time. And went back to the marquee. She had no idea what she was doing. She had done ballet as a kid, so she tried out a few pirouettes, ripping off items of clothing as she span. “She still had this incredible body,” said India, “despite having three kids.” She won the contest, and got a job taking her clothes off every lunchtime for businessmen in Perth. Margaret took to dressing as Wonder Woman, before undressing again.

She had been placed in a migrant hostel in Noalimba, in Perth, where she was raped within two days of her arrival by the caretaker. It was a regular habit of his with newbies. The police were aware and turned a blind eye. Was the guy not doing a fine job of caretaking after all? So when Margaret snatched the kids – technically “wards of the state” – and took off with them she was trying to save herself as well as them.

“I told them {the Fairbridge Farm authorities} I was staying in a hotel for Easter,” Margaret said, “so the kids could come and stay. They dropped the kids off. Of course, I wasn’t really staying there. I didn’t have that kind of money. I was just sitting in the lobby. We actually spent the night in a Salvation Army dorm.”

They hitchhiked across the vast Nullarbor Plain and kept on going, right across the continent, from West to East. Margaret was wearing red high-heeled shoes, which probably helped. She wrapped the kids in a cloth bearing the message “SOS”, scribbled in lipstick. As soon as they crossed the state border they became fugitives, pursued by irate social workers, one of whom had a crush on Margaret. “Once you’re on the run,” she said, “there’s no turning back – you have to keep going.” After a month on the road, they ended up in Surfers Paradise, on the Gold Coast, south of Brisbane. They arrived in time for the March 1979 Stubbies, one of the first international surfing contests of its kind, the beginning of the professional era.

As someone once said, Australia is not a sea-going nation, it is a beach-going nation. Duke Kahanamoku, the Hawaiian Olympic gold-medal-winning swimmer, first took surfing to Australia in the middle of the First World War. It always looked like a better option than dying in the trenches, or Gallipoli, or Vietnam. So Margaret decided to become a legend, an archetypal beach babe bearing an uncanny resemblance to the young Brigitte Bardot.

She was quickly adopted as his personal icon by Dick Hoole, who was one of the top Australian surf photographers of the era, and described her as “a free-spirited female who refused to wear clothes”. On a poster advertising the Stubbies in Burleigh Heads, she is rated as a “1000-1” outsider. The other outsider also on 1000-1, Ted Deerhurst – a nomadic British aristocrat turned our first pro-surfer – proposed to her. “I turned him down,” Margaret said, lying in Hollywood hospital bed, with her heart being carefully regulated. “I preferred to get married to a string of violent, abusive losers. I regret that now.”

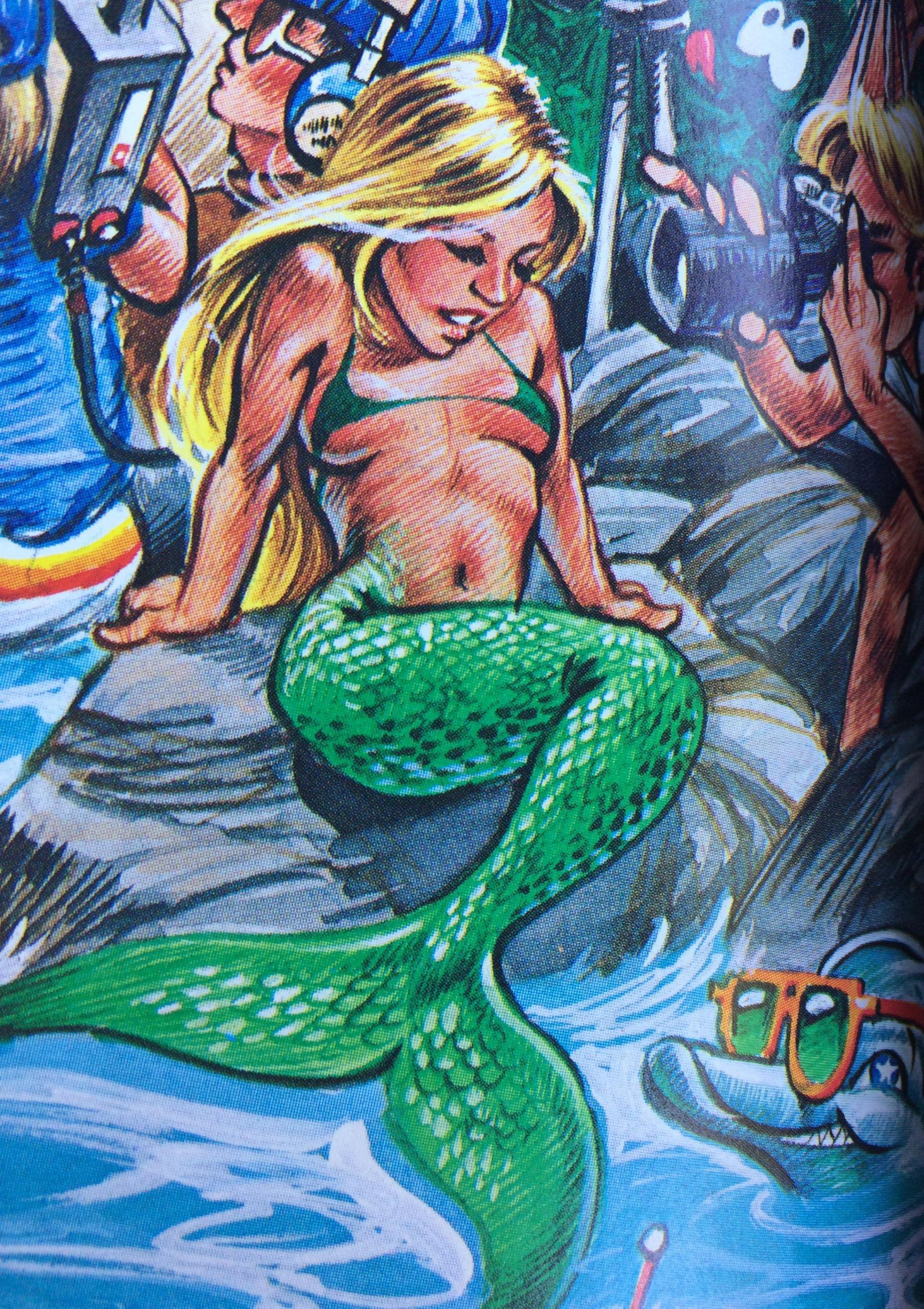

She was beloved of the tabloid press of the era, whether on the Gold Coast or at Bondi Beach. “She became a tourist attraction,” said India. A cover of Surfer magazine, dating from December 1982, depicts her as a mermaid being photographed by Dick Hoole. Maybe it was not so surprising that, a decade or two later, India would go to Los Angeles to study at the UCLA film school. And that she is now, at 45, a fully-fledged director. Margaret went to live on the north shore of Oahu, in Hawaii, where she married yet another nightmare guy. And then ran away yet again, a year or so ago, this time to Los Angeles, where she and India have now been re-united.

India says now: “We were lucky. Many women didn’t get their kids back until they were much older and the kids were really damaged – and the parents too.” India is in talks with the Kevin Spacey Foundation about making her short film into a full-length feature or TV series. I hope it works out. I would go and see that movie. As India was making her mother comfortable in her hospital bed and getting her “decent” for visitors, Margaret was making notes for a memoir.

“How many times was I married, Indy?” There was some debate on that point. Her daughter has become her guardian angel and the repository of memory. Just as her mother saved her from Fairbridge, so now India Dupré is returning the favour and saving her mother from oblivion.

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of ‘Make Me’ and teaches at the University of Cambridge. Follow @andymartinink

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks