A Life in Focus: Alexander Solzhenitsyn, dissident writer whose account of life in the gulag exposed the tyranny of Soviet Russia

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Tuesday 5 August 2008

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alexander Solzhenitsyn bestrode Russian literature for decades and would in December mark his 100th year. His obituary follows.

For much of the 20th century, large sections of the populace of one of the greatest nations of the earth were held in virtual slavery by their own government. That modern system of serfdom – far more rigorous and extensive than any Siberian exile – was known as the gulag, after its Soviet acronym. Its historian and unmasker was the great writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn. With his death comes to the end an important chapter in the long tradition of Russian moral prophecy.

Solzhenitsyn’s book Arkhipelag Gulag (The Gulag Archipelago), a three-volume work setting out the history of the Russian labour camps since the time of Lenin up to the present, was a bombshell on its publication in 1973. For the first time, the full history of the regime’s repressions was chronicled in intense detail, with no extenuation given to “later aberrations”: Lenin was blamed for the débâcle as much as his evil successor Stalin. The literary and political importance of the work’s appearance as an event in the history of the epoch can scarcely be exaggerated. In fact, it is not implausible to measure from this date the beginnings of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918 in Kislovodsk, a spa town in the northern Caucasus where his maternal grandfather, a self-made Ukrainian millionaire, owned a large villa. The Solzhenitsyns themselves were of Russian peasant stock. Following the southern expansion of the empire in the 19th century, they had settled in the region of Stavropol, east of the Crimea, where successive generations cultivated the land. Various ancestors had been narodniki, supporters of the free peasant movement: left-liberal in sentiment, though mainly patriotic and God-fearing, with sympathies directed more towards Tolstoy than towards Marx.

Solzhenitsyn never knew his father, Isaak, a Moscow university graduate and officer in the Tsar’s army who was killed in a hunting accident three months before the boy was born. His mother Taissia brought the child up in Rostov-on-Don, a port city retaining something of the colourful cosmopolitan character of its origins throughout the civil war and during the subsequent victory of Bolshevism. Despite poverty (Taissia never remarried), the atmosphere of the household was cultivated and, through the influence of a beloved aunt, Irina, sympathetic towards Christian orthodoxy.

The child Alexander was precociously clever. By the age of 11 he had read a large swathe of the Russian classics including War and Peace. As he grew into late adolescence he became firmly converted to Marxism and to the justice of the Soviet cause, though this seems never to have interfered with his first and overriding childhood ambition, to make a name for himself in the field of literature. Already by 1936, aged only 18, he was sketching an epic historical canvas on the subject of 1917, the year of revolutions – something that, with appropriate changes in outlook and incident, would eventually transmute into the longest (if not the greatest) of his adult works, Krasnoe koleso (The Red Wheel, completed in 1993).

Literature, however, was at this stage a secret or at best a leisure-time occupation. With a strongly practical bent of mind inherited from his mother’s side of the family, Alexander Solzhenitsyn chose mathematics and physics as university subjects – in his home town of Rostov, rather than travelling, as he might have done, to Moscow. His years at university coincided in the wider Soviet sphere with the full onslaught of the Red Terror. Although privately disenchanted with Stalin, Solzhenitsyn was not yet in any real sense a critic of the state: long into his imprisonment he was to remain strictly speaking a Leninist, arguing that while the outcome of the revolution had been perverted, the project had been sound, even noble.

As a young man he was dashing and popular. His stay at university was conventionally successful and crowned with academic honours. Thus it was something of a surprise to his contemporaries that he chose on graduation to take up a comparatively humble teaching post as a village schoolmaster in Morozovsk, a sleepy provincial backwater where he settled with his young bride Natalya Reshetovskaya at the beginning of 1941.

Hitler’s invasion of Russia in June of that year reawakened in Solzhenitsyn his intense boyhood patriotism. He served briefly and without distinction in a Cossack regiment (his ignorance of horses giving rise to mockery), then succeeded in transferring himself to officer training college, graduating lieutenant of artillery in late 1942 with a speciality in the acoustic pinpointing of gunfire.

During two subsequent years of active service, Solzhenitsyn took part in the great counter-offensive which, in the wake of Stalingrad, saw the German army slowly pushed back through the conquered territories of Ukraine and Belorussia, up to the borders of Germany and beyond. He was present at the Battle of Orel, the second great Russian victory of the war (in August 1943).

In quieter moments he continued to write poems and short stories and to correspond with family and friends, including a friend from schooldays, Nikolai Vitkevich (“Koka”) whom he had met up with again for a brief period in the months of mobilisation. Almost light-heartedly, it seems, the pair had concocted a “a society for the reform of Russian customs”, complete with parliamentary manifesto (“Resolution No 1”) and a blueprint for bringing Russia out of feudalism.

Letters between the friends referring to Stalin disparagingly as “the mustachio’d one” and “pakhan” (“big shot”) fell into the hands of the political authorities. Thus it came about that in February 1945 at his forward billet in Prussia, Solzhenitsyn was arrested, stripped of his officer’s epaulettes and charged under article 58 of the Soviet criminal code with “taking part in anti-Soviet propaganda” along with “funding an organisation hostile to the state”.

How far were Solzhenitsyn’s dissident views at this stage of his life typical of his training and cadre? It is difficult to be sure. On the one hand, although he hated Stalin, the more savage aspects of Soviet Communism had passed him by. Like a surprisingly large number of his fellow countrymen, he knew nothing at first hand of the mass arrests, the tortures and the forced deportations that had characterised Soviet life in the Thirties.

On the other hand, he was a writer and therefore an observer. And he had managed to retain from childhood – what may have been rare in Soviet society – both a religious outlook and an irreducible belief in the individual. Of the 30 officers in his battalion, he was one of only two who throughout the war declined to become a member of the Communist Party. His scepticism seems to have been as ingrained as his patriotism.

Solzhenitsyn was transferred under guard to Moscow. (He himself directed his Smersh minders – out-of-town provincials – to the gates of the Lubyanka.) In view of the gravity of the charges against him, it is perhaps surprising he received a sentence of “only” eight years’ hard labour, handed out by a Soviet special court. Before the war, he would have been shot. There was a certain chaos around and, a final piece of luck, his interrogator was lazy – omitting to examine, for instance, the incriminating diaries that fell into his hands along with Solzhenitsyn’s personal effects.

So began Solzhenitsyn’s journey to the gulag: from the Lubyanka via a series of transit camps – Butyrki, Krasnaya Presnya, Kaluga Gate – in each of which he encountered some new graduated rigour (at the same time some new facet of human personality, some fresh example among inmates of courage and endurance) before ending up, in 1950, in the harsh camp of Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan, where, as he later said, he “touched bottom” in both the good and the bad senses of the phrase. (This was the camp whose regime he was to describe unforgettably in A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, 1962 – first published in the journal Novy Mir as “Odin den’ Ivana Denisovicha”.)

Meanwhile, though, there had been cushioning spaces on the road: intervals, even, of comparative freedom. In one of the questionnaires sent round the prison system by a regime hungry for technical specialists, Solzhenitsyn claimed a knowledge of atomic physics. In fact this knowledge was almost non-existent: he had merely read an American book on the subject. But the hint was enough to have him transferred to a special research prison, Marfino, housed in a former seminary on the outskirts of Moscow – where, however, instead of pursuing high-level research, he at first busied himself perfecting a scrambling device for Stalin’s personal telephone service.

It was in Marfino that he met and became friends with two extraordinary individuals, Lev Kopelev and Dmitri Panin, characterised respectively as the ideological opponents Rubin and Sologdin in V kruge pervom (The First Circle, 1968), the novel that earned Solzhenitsyn the 1970 Nobel prize. In the debates which the inmates engaged in during their leisure-time on the relative merits and demerits of Marxism, Solzhenitsyn came to feel he had stumbled into a magic circle, “by accident, one of the freest places in the whole of the Soviet Union”. Panin was the more important of the two from the point of view of Solzhenitsyn’s political education, persuading the writer that it was Marxism itself – the doctrine of Communism – rather than its subsequent mutation into Stalinism, which was the aberration from human norms, and the root cause of his country’s catastrophe.

Panin had another significance for Solzhenitsyn in his personal life, as a model of unswerving ascetic steadfastness. The material privileges enjoyed by the prisoner-intellectuals in Marfino could be withdrawn at the first sign on non-cooperation. But the threat of their removal seems not to have impressed either Panin or Solzhenitsyn. Following a showdown with the authorities, the pair were pitched back into the gulag, continuing their journey together as far as Ekibastuz.

The regime there was the harshest Solzhenitsyn encountered, both in terms of physical toil – gruelling labour as a bricklayer and then as a smelter’s mate – and of the dehumanising treatment meted out by the authorities. (Names had been dispensed with and prisoners were referred to solely by numbers.) At the same time Solzhenitsyn became afflicted by cancer – the first of two bouts – and had to endure the horrors of prison surgery and its makeshift aftermath.

Still, in other ways there was hope in the air for the first time since his capture. Tremendous camp rebellions in 1951 succeeded, against the odds, in improving conditions and, above all, morale. Just as important, it was in this period that Solzhenitsyn finally returned fully to the Christian faith which was to succour his literary ambitions and to mark forever his mature view of history.

Solzhenitsyn’s release from jail, in fact, coincided with Stalin’s death. He heard the news within the first week of his sentence of “perpetual exile” in the little town of Kok Terek in Kazakhstan, where in due course he succeeded in finding work as a schoolteacher. The years from 1953 to 1961 were spent in lonely isolation, completing first drafts of the novels that were later to make him famous. The background to this endeavour – what allowed it to take place – was the steadily improving political climate that came after Stalin’s death, and especially in the wake of the 20th Party Congress of October 1956 when Nikita Khrushchev famously denounced his predecessor’s crimes. Solzhenitsyn’s sentence of exile was lifted in 1956; he settled in Ryazan with his wife Natalya. Pardon from the state came a year later – but no monetary recompense or apology: as there was to be none for the thousands of his fellow inmates recently let out of camps or still languishing there.

A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published, on Khrushchev’s personal recommendation, in late 1962, and instantly shot Solzhenitsyn to fame. Yet almost in the same month the state began the slow move away from relative liberalism (the end of the “thaw”) which was to mark the changeover from the Khrushchev to the Brezhnevite era. Rakovyi korpus (Cancer Ward), completed in 1962, was more radically critical of the regime than Ivan Denisovich, and The First Circle more outspoken than either of these. By 1965 it was becoming clear that neither of these later works had much chance of publication on home ground. (The battles surrounding Solzhenitsyn’s attempts to get published, and his relations with the great Novy Mir editor Alexander Tvardovsky, are recounted in his highly readable memoir Bodalsya telenok s dubom, (The Oak and The Calf, 1975.)

Nineteen sixty-five also saw the confiscation of Solzhenitsyn’s archive by the KGB, minus, miraculously, his drafts for Arkhipelag Gulag (The Gulag Archipelago). From now on it was only a matter of time before a showdown with the authorities – though Solzhenitsyn was protected by the genuine popularity he enjoyed across all ranks of Soviet society, and also by a certain innate cautiousness that prevented him, for example, from speaking out as forcefully as he might have done in favour of contemporary dissidents like Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuri Daniel.

The great question of the hour was whether, being denied an opening on the home market, he should publish abroad. (It was the decision to go for this latter option that had caused Sinyavsky and Daniel to be dubbed traitors.) Solzhenitsyn prevaricated. Manuscript copies of his major works including The Gulag Archipelago were all safely in the hands of western sympathisers by mid-1968, but still Solzhenitsyn was pressing for home publication – at least of Cancer Ward, and maybe also for a slightly expurgated version of The First Circle. It wasn’t to be. Events took on their own momentum. An English translation of Cancer Ward was published “without personal authorisation” in August 1968, followed a few months later (with much greater fanfare) by the appearance in America of The First Circle. Solzhenitsyn’s fame was now worldwide.

The authorities at first contented themselves with low-level sniping. By a series of Byzantine manoeuvres, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Writers’ Union in 1969. The following year, support came from the West in the shape of the Nobel Prize for Literature. But Solzhenitsyn refused to travel to Stockholm to receive it, rightly fearing that, once out of the country, he might never be allowed to return. Such an outcome was not part of his aim at this stage. The huge work he had embarked on, a history of the immediate years leading up to the 1917 revolution, required further researches “on the spot”. And besides, as a patriotic Russian to the core, he had no wish to desert his native soil.

So, in the years up to 1974, Solzhenitsyn lived perpetually on the brink of re-arrest; but he found protection in powerful friendships (for example, with the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich), and also by virtue of the fact of his international pre-eminence. In official circles it was the beginning of détente; the non-persecution of Solzhenitsyn, and of Solzhenitsyn’s friend the nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, was for a while the price the Soviet Union paid for having its peaceable aims taken seriously.

Even so, there were limits to the authorities’ patience. Solzhenitsyn realised the game was up the moment, in September 1973, when it came to his ears that the KGB had – finally – discovered a concealed manuscript copy of The Gulag Archipelago. Through intermediaries, he immediately authorised the publication of the Russian text of the work in Paris, followed by English translations in America shortly afterwards.

Orchestrated press campaigns in the pages of Pravda and Literaturnaya Gazeta vilified Solzhenitsyn as a traitor and enemy of the people. On 12 February 1974, he was arrested for the second time, interrogated in Lefortovo Prison, and the following day bundled onto an aeroplane out of the country, into an exile that was to last for 20 years.

Solzhenitsyn’s long sojourn in the West – first in Germany, subsequently in a remote farmhouse in Vermont, in the United States – was taken up in the private sphere with the completion of his sprawling epic of the pre-revolutionary years: he worked on it every day without fail. At the same time, the years saw the re-establishing of a happy family life in the company of his second wife Natalya Svetlova and their children. In the public sphere, Solzhenitsyn became known for his continuing fierce denunciations of the Soviet regime, and his equally caustic scorn for Western materialism.

The period of glasnost ushered in by Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms saw the vindication and triumph of Solzhenitsyn’s life work in the publication, in his homeland, of his major works – including The Gulag Archipelago – accompanied by enormous discussion. In the wake of the reforms and, in particular, of the failed coup d’état of August 1991, he determined to return to Russia. (There had been an open invitation from Boris Yeltsin.)

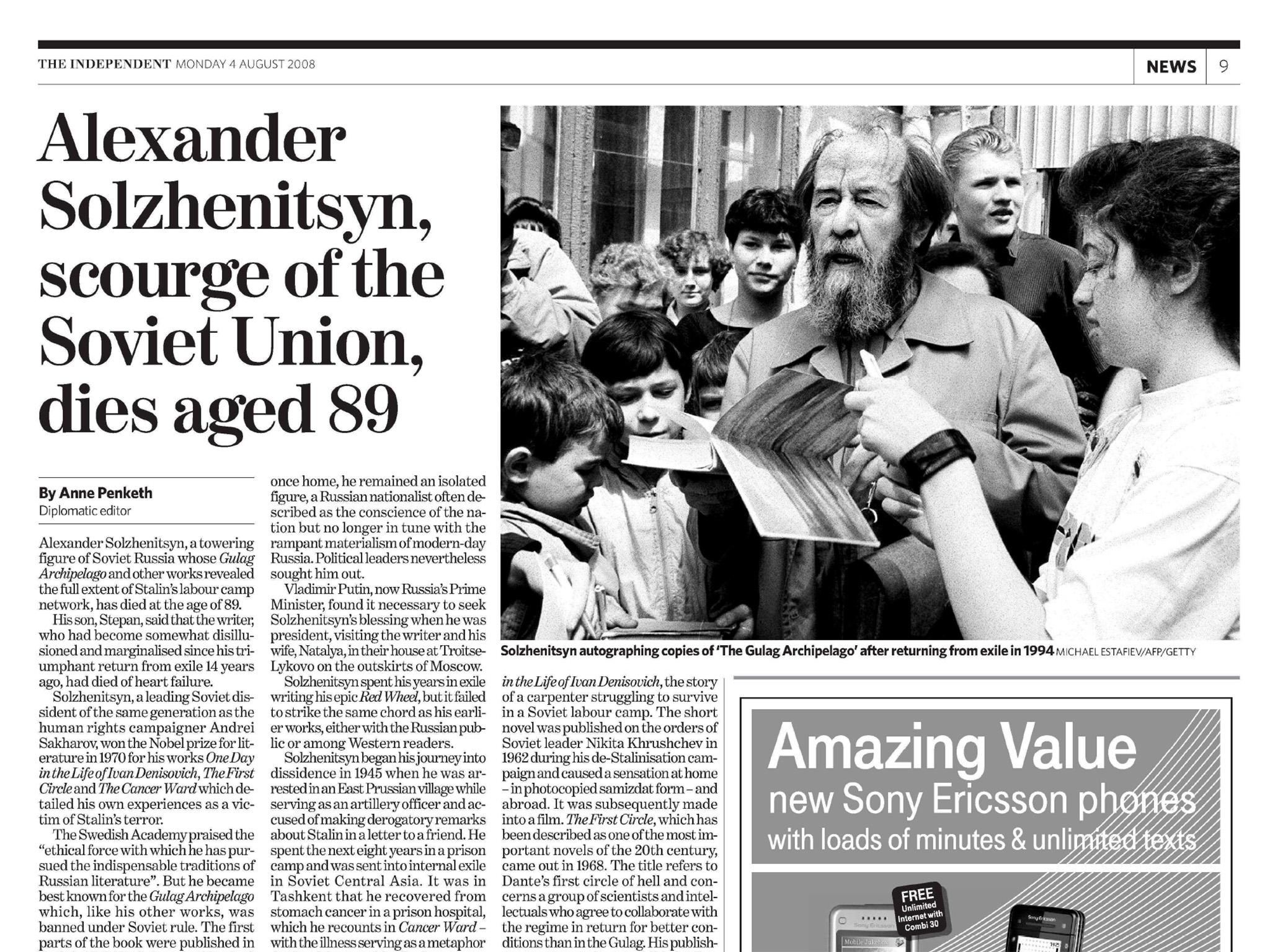

However, delays in completing The Red Wheel, combined with difficulties in finding a suitable apartment in Moscow, put off the actual date until 1994, by which time the impact of his arrival was somewhat lessened. None the less, his long train ride from Vladivostok back to Moscow was an event of national importance, widely covered also by the world press.

Solzhenitsyn continued to publish widely, mainly in Novy Mir, to which he contributed an acerbic memoir of his years in the West, castigating the many helpers who had somehow or other failed to live up to his expectations. (Of his collaborators, only his much-loved second wife seemingly escaped this inevitable final disappointment.)

His two-volume history of the Jews in Russia, Dvesti let vmeste (Two Hundred Years Together, 2002), caused renewed controversy, resuscitating charges of covert antisemitism that had appeared now and again (usually maliciously) throughout his career. In fact his view on the subject was a complex and nuanced one, as was only to be expected of a man whose second wife was Jewish, and whose three sons from that marriage had been brought up in the Judaic faith.

The purpose of Solzhenitsyn’s return, of course, was to lend his authority to his country’s renewal after the nightmare; but obstinately the nightmare continued. Crime, poverty, the grosser forms of materialism, conflict with Chechnya: on each of these issues Solzhenitsyn had important things to say, but the country at large became less and less inclined to listen to him. A fortnightly television programme on which Solzhenitsyn “aired his views” was discontinued in the late Nineties on account of poor ratings.

Boris Yeltsin, as mentioned, had always admired Solzhenitsyn, and offered him honours which were refused. Vladimir Putin, when in turn he came to power, visited the sage in his house on the outskirts of Moscow and Solzhenitsyn received undoubted pleasure from this visit, in later years speaking with approval of Putin’s policies. In June last year he accepted the Russian State Prize from Putin.

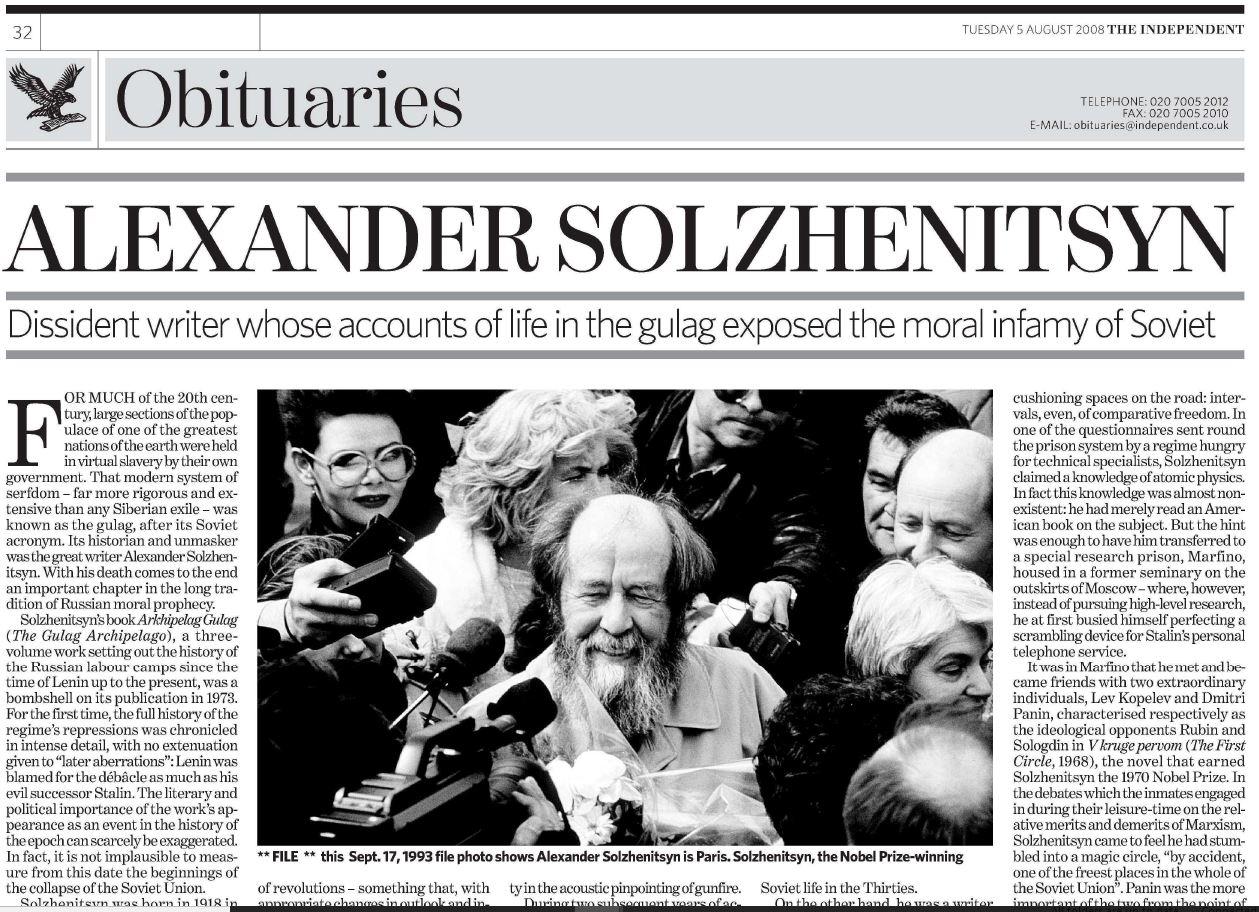

The public image of Solzhenitsyn had something biblical and prophetic about it. His Christianity was of the Old Testament variety; he was unafraid to call his fellow countrymen to repentance. His appearance was fittingly austere: tall, bearded, with a slight schoolmaster’s stoop, he had attractive blue eyes, and a straightforward, open, trusting countenance which inspired confidence and drew people towards him. From the moment after his release when he began seriously bearing witness to his times, he seemed to live not quite for himself, but as it were “in trust” for those who had perished in the purges.

To this end, his spare time was rationed to the most stringent specifications. Every moment of the working day was precious. Every moment not spent writing was seen as a derogation of duty. This made him seem inhuman to some; and the loyalty he inspired from those around him was sometimes bought at a cost. His enemies (of whom there were many) dubbed him fanatical, an accurate epithet.

Judgement about the literary quality of his writing has always been mixed. The personal, sarcastic bent of his style has been thought overdone or rhetorical. Others, however, see him as one of the giants of Russian prose. His literary vocabulary was extensive and always growing. He was fascinated by Russian proverbs and by the lost, demotic pre-revolutionary speech which he sought to reintroduce into common currency, along with the famous “slang” of the camps. Elsewhere – in Cancer Ward and The First Circle – his literary model was Tolstoy and the tradition of seamless, spacious Russian storytelling, enlivened however, in his later writings, by modernist “collage” effects taken raw from documents and newspapers of the time.

The unresolved literary question about Solzhenitsyn lies in the value of The Red Wheel, the massive documentary novel in four parts covering the history of Russia from 1914 to the collapse in 1917 of the provisional government. It was composed over a period of 30 years, mainly in isolation in rural Vermont. Few modern readers, perhaps, have the time or energy to spare on a novel of 5,000 pages – especially about a time in the past that has already been covered elsewhere by historians. Only history will decide whether the book succeeds in asserting its authority.

Solzhenitsyn’s overall importance, however, is finally as a moral rather than a literary phenomenon. He was a writer, but above all a prophet, a figure on the world historical stage. He contributed massively to the destruction of an ideology – the most powerful belief system of the early 20th century. The prestige of the Communist experiment had a surprisingly long duration both in the Soviet Union and among intellectuals abroad. After Solzhenitsyn, it became impossible to ignore both the moral infamy of Soviet Communism, and its categorical ineptness as a system of government.

Of course, there have been other witnesses to say this too. But Solzhenitsyn’s was the overpowering presence. It was in his voice, and in his accents, that the indictment was classically formulated.

Alexander Isayevitch Solzhenitsyn, writer, born 11 December 1918; died 3 August 2008

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments