A Life in Focus: Iris Murdoch, novelist and philosopher

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Iris Murdoch, from Wednesday 10 February 1999

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

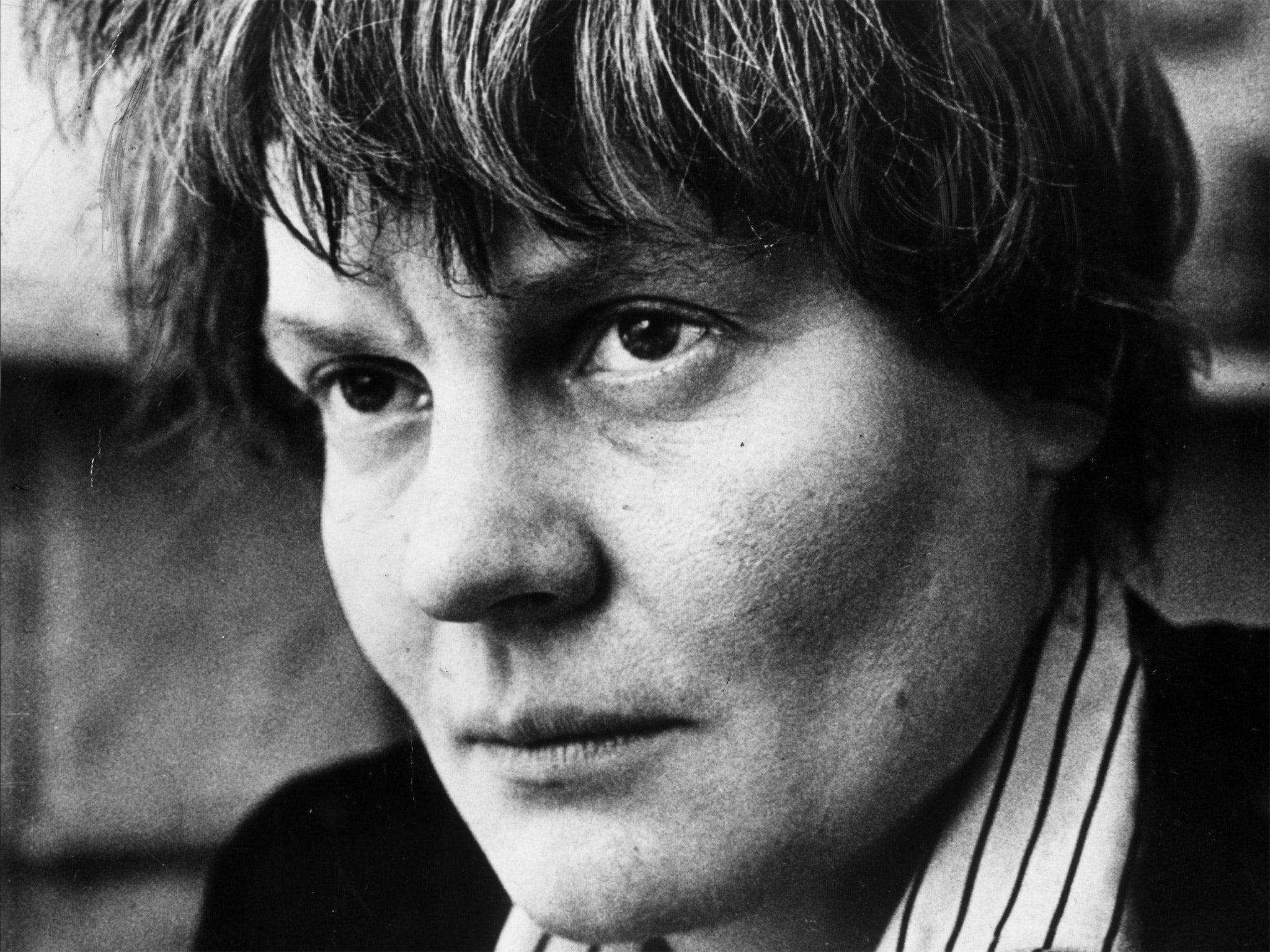

Your support makes all the difference.Iris Murdoch was a national institution. Her name has entered the language in adjectival form, as have those of Proust, Kafka and Pinter – once you embark upon reading a Murdoch novel you are caught up in a whole world, a world whose chief characteristic is hordes of characters, each of whom seems to be in love with more than one of the others, and to do improbable things that seem startlingly apposite.

There are dark aspects to the Murdochian universe: adultery, incest, erotic follies, betrayal, deception, religious anguish, guilt and even murder, are part of her stories, but these are tempered by a strain of metaphysical speculation and ethical concerns – she was a trained philosopher.

Murdoch also portrayed characters who were happy, even in a state of bliss (this is particularly true of the animals who populate her tales – they have personalities, too, and are always blessed with sunny dispositions). Above all, she was a consummate storyteller, prodigiously inventive and generous, in the realist tradition of Dickens, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky: in whose company she would have liked to have found herself.

The Sea, the Sea (1978) is a reasonably typical Murdochian story. Its protagonist, the well-known theatre director Charles Arrowby, is not an evil man – simply completely self-centred. The plot is one of obsession, and borrows from The Tempest the theme of the use and surrender of magical power. Charles, a bachelor aged more than 60, has retired to a lonely seaside house, “to repent of a life of egoism”, and lead a simple, solitary life. He cooks horrifyingly disgusting meals for himself (the menus were suggested by Murdoch’s husband, John Bayley, who would shock people by pretending to find the food perfectly nice), and soon discovers that the house is haunted.

The tale rattles right along, with something odd emerging from the sea, women making unwelcome reappearances in his life, kidnapping and violent death. The tragicomic world is further populated by Charles’s male helpers, who include an old rival, his cousin James, a soldier turned Buddhist. The atmosphere of the novel is intense, the story gripping – it’s a real page-turner, though it’s an intellectually demanding book about forgiveness and violence.

Murdoch was born in Dublin, presumably because her mother, nee Irene Richardson (she and her sister later added the name Cooper) had returned there because she had some female relations there, including her sister, to help with the birth. Some sources say that her mother and father, Hughes Murdoch, moved to London when Iris was one year old, and others say she was nine. In fact, her biographer Peter Conradi has discovered that her father had a London address in 1914. As a civil servant in Ireland he was given the choice of staying on in Dublin or being posted to Belfast or London – he thought it prudent to go to England. Iris Murdoch always felt passionately Irish, but she also felt that it was possible at the same time to be British. She was not only of Ulster Presbyterian stock, but had some ancestors that were Plymouth Brethren and Quaker.

She had a particularly happy childhood, which she attributed to being an only child. Her mother had a fine voice, and considered training as a singer, but marriage put paid to that ambition. Murdoch loved to sing herself, and, after a good lunch, often did. She had a high, reedy version of what she called her mother’s “shebeen soprano”. Murdoch was educated at the Froebel Educational Institute in London, and her boarding school was the progressive, high-minded Badminton School, Bristol. It was there that she acquired her facility with, and love of languages, that led her to list “learning languages” as her recreation in Who’s Who.

In 1938 she went up to Somerville College, Oxford, where she read Greats, was introduced to philosophy and got a first. She went up at the same time as the philosopher Mary Midgley, and in 1939 was joined at Somerville by another philosopher, Philippa Foot, with whom she lived during the Second World War. Roy Jenkins and Kingsley Amis were contemporaries, and remained lifelong friends. From 1938 to 1942 she was one of 30 open members of the Communist Party at Oxford. Sometimes she said she’d been a communist since she was 13.

Just over a week after her examinations in 1942, she was conscripted as an assistant principal at the Treasury. She was back in London for the second stage of the Blitz, and stayed at the Treasury until June 1944, when she joined the United Nations Rehabilitation and Relief Association. Murdoch spent the first 15 months with UNRRA in London, and left for Brussels in early September 1945, when, almost at once, she met Jean-Paul Sartre and Chico Marx.

Following three months in Belgium, she worked in four different camps in Austria, as an administrator. Dr Jancar, a Slovene who was one of the 30,000 who fled Yugoslavia, told Peter Conradi that Murdoch was impatient with red tape and so unhappy about the conditions of the inmates of the camps, who had to subsist on near-starvation rations, that once she took the keys and illicitly opened the railway carriages containing the potato cargo. On that occasion, Jancar remembered, he found some sweets in his pocket, placed there by Murdoch for him to give to his wife. Her work with displaced people in the camps meant finding them blankets and food and sometimes new papers and even a new nationality.

She returned in July 1946, having spent two years with UNRRA, and applied for a Commonwealth Fellowship to the United States. An inveterate truth-teller, she ticked the “yes” box beside the question “Have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” The result, which annoyed her for the rest of her life, was that she was refused a visa.

In 1947 she was awarded the Sarah Smithson studentship in philosophy at Newnham, Cambridge. There she met Wittgenstein, and, though she did not fall under his spell in the usual way of the postgraduate students who came into contact with him, she remarked the “shocking immediacy” of his presence. Then in 1948 she got a fellowship at St Anne’s College, Oxford, where she taught philosophy until 1963.

She had fallen in love with Frank Thompson, the older brother of the historian EP Thompson, and it was assumed they would marry. But Thompson fought with the partisans in Macedonia and joined them in their march to Sofia, and he was captured and executed by the Nazis. Her next romance was with Franz Steiner, a Czech Jewish refugee who was a poet and anthropologist. He had lost both his parents in the death camps, and had a heart attack in 1949, from which he never recovered. Conradi finds elements of him in Peter Saward in The Flight from the Enchanter, which, though it was published in 1956, was actually written before her first published novel, Under the Net (1954). Her social circle included many refugees, including Elias Canetti. Of the three well-known Hungarians, she disliked Arthur Koestler, while she was fond of Thomas Balogh and Nicholas Kaldor.

Though Murdoch became a philosopher, she had thought seriously about becoming an art historian – she made an intense study of Renaissance pictures, and all her life she looked at pictures in a way rare among non-specialists. It is not well known, but she herself had painted at school and during the war. So it was not so odd that on leaving St Anne’s she went from 1963 to the Royal College of Art, where she was invited by Christopher Cornford to teach the general studies course. One often meets artists lucky enough to have been taught by her, such as the successful painter Bill Jacklin. At the Royal College, Murdoch was the contemporary of Janie Ironside and Humphrey Spender. In 1967 she left, and went on to write 27 novels, some plays, poems and philosophical treatises.

In the spring of 1953 she met John Bayley, then a very junior instructor in English at St Antony’s College, Oxford. She was in the midst of much emotional turmoil and, as she later said to the novelist AS Byatt in a moment of retrospection, “Why should I be cheated of happiness?” She wasn’t. In August 1956 they began what became a legendarily happy marriage. They were the subject of endless anecdotes – from John gossiping to one lunch guest while Iris explained Sartre to another, to the weekend host who, taking a tea tray to their bedroom, found Iris learning German irregular verbs while John flipped through the pages of a downmarket women’s magazine. Or John would tell a confidant, “I don’t like cats, but Iris does”; while the same person would receive a confidence from Iris that she didn’t like cats, but John did. Iris was not much of a cook, though she was proud of her stifado, a Greek dish of beef, olives, tomatoes, wine and vinegar.

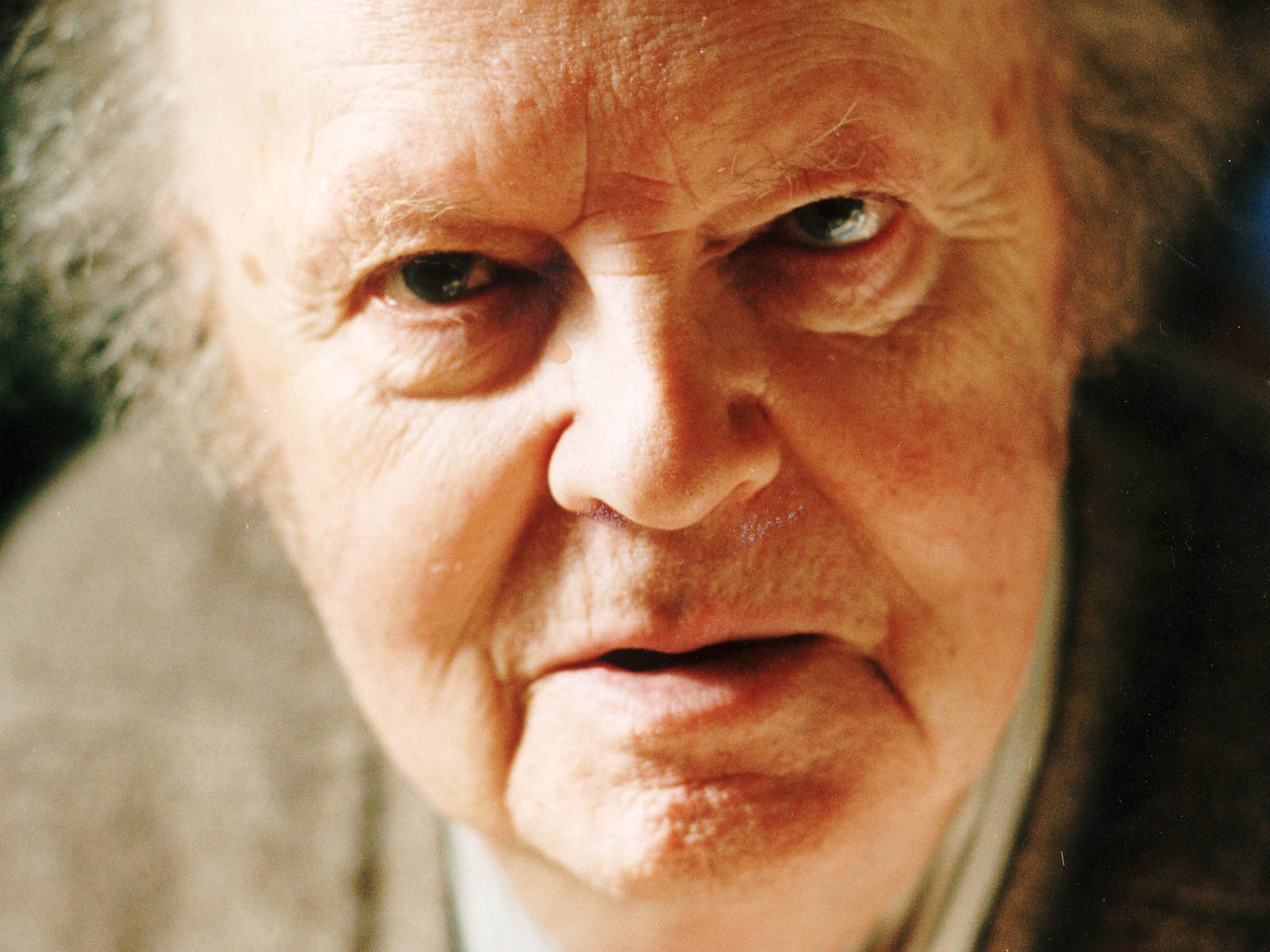

The Bayleys were enormous fun to be with, together and separately, and were much loved by friends such as Lord David Cecil, Christopher and Baillie Tolkien and Andrew (AN) Wilson. For many years they lived in a large, undisciplined house at Steeple Aston, with stacks of books in unlikely places and a sink full of washing up. In later years Iris’s appearance got more and more eccentric. She often wore one particularly beautiful item of clothing, such as a scarf, and walked about in plimsolls, which eased the pain of her arthritis. She was thus shod in 1987 when she went to Buckingham Palace to be invested DBE.

Peter Conradi tells how he learned in yoga classes how to stand on his head. One day in 1984, having lunch in Dino’s, he offered to show her on the spot. She tensed up a little, and Conradi desisted, but the episode was incorporated into The Good Apprentice published the next year. Her novels were never romans à clef, but there are recognisable portraits of people she knew, especially in the early novels. But when friends thought they had been drawn on for a character in one of her novels, she said on a radio programme, “it was generally vanity”.

Murdoch won a vast number of prizes, from the James Tait Black Memorial Prize to the Booker Prize, and was even rumoured to have been nominated for the Nobel prize. She also collected a large number of honorary degrees. She was faithful to her publishers, Chatto & Windus, but would not allow so much as a comma to be changed in her hand-written manuscripts. After she took on Ed Victor as her literary agent, her royalties became considerable – it has been said that she gave most of them away.

Despite her obvious goodness, Murdoch was modest and self-effacing. John Russell tells the story of someone asking her if it was true that a biography of her was being written: “Yes, it was, she said, much to her surprise; that she might be the subject of an almost universal curiosity had never occurred to her. ‘I don’t read biographies, but apparently people buy them. But me? What is there to say about me?’” She was, however, despite her idiosyncratic appearance, enormously attractive. She had the ability to fix her gaze upon you with complete concentration, in the way a child does. It suited her unworldliness that she was interested in Buddhism, and hoped mankind might one day evolve a non-supernatural religion.

In her last years she suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, and was tenderly nursed at home in their very un-donnish North Oxford house by John Bayley, until, three weeks ago, it became impossible to care for her singlehandedly, and she went into the Vale, a nursing home that specialises in Alzheimer’s patients. She was able to socialise, after a fashion, almost up to the end. As John Bayley says in his recently published, loving memoir Iris, she became like a child, mostly docile and very affectionate. Friends first noticed something was wrong about 1995, about the time of the publication of her last novel, Jackson’s Dilemma. I asked her then if she had, as was her habit, begun to think about her next book. She said: “I don’t think there will be another one.” Her friends knew she was having memory difficulties, but I was surprised that she was so final about it, and I asked what she would do with her time: “Read,” she said, “and sing.”

John Bayley had the help of some devoted friends, especially Peter Conradi and Jim O’Neill. Iris and John often went to their cottage in Wales, even late on in her disease. To the end, Iris retained her bright smile, greeting and seeming to recognise those who loved her. Having refused food and drink, she simply faded, peacefully, with John at her side.

Jean Iris Murdoch, novelist and philosopher, born 15 July 1919, died Oxford 8 February 1999

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments