Lesser-known K-pop bands struggling amid the pandemic

While popular K-pop bands like BTS and Blackpink have gone from strength to strength during the coronavirus pandemic, lesser-known acts are struggling

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.While popular K-pop bands like BTS and Blackpink have gone from strength to strength during the coronavirus pandemic, lesser-known acts are struggling.

The gap between the world famous and more obscure K-pop acts has never been greater — a situation exacerbated by the pandemic, which has been a huge blow to music-related industries around the world.

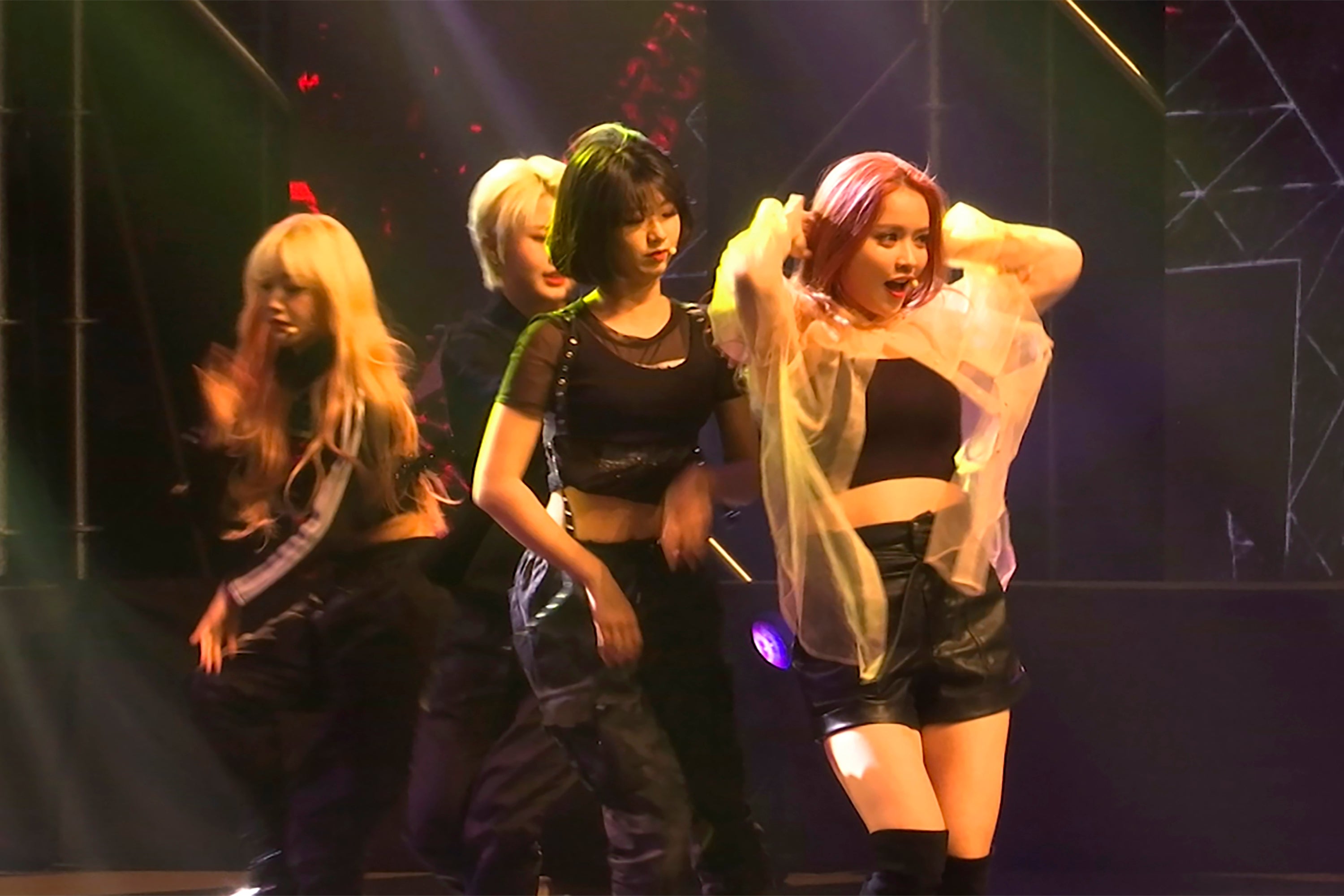

Global K-pop bands have managed to expand their fan bases over the past months through various online gigs. But others, including Girls Alert, have seen concerts canceled and personal appearances postponed due to social distancing measures.

Girls Alert, which debuted in 2017, didn’t see it coming, just like everyone else.

By late 2019, the young five-piece group — made up of Jisung, Saetbyul, Gooseul, Narin and Seulbi — had toured all around South Korea. Like other lesser-known bands, they've performed pretty much everywhere, from military bases to orphanages.

The members of Girls Alert said they initially chased glitz and fame just like other new K-pop acts. But they said that after their debut, they found that the reality of the business was far different from what they had expected.

Jisung said she and the other members led a “dirt spoon” existence after their debut, a term for a person who earns relatively little in South Korea with little chance for social mobility.

The singer who is in her early 20s, said the band had to take care of everything — outfits, dance training, hair and makeup — by themselves, unlike more popular K-pop acts that have entire entourages of staff members. “We had to get clothes from Dongdaemun and plan our outfits with accessories all by ourselves,” Jisung said, referring to a large wholesale market in Seoul with maze-like alleyways.

K-pop music videos are known for their sleek and futuristic aesthetics, a contrast to Girls Alert's humble video filmed at Olympic Park in Seoul. Jisung noted that there were balloons in the video. "We had to blow them up one by one by ourselves,” she said.

While juggling her band responsibilities, Jisung also had to work at a sushi restaurant and help out at her parents’ cold bean noodles restaurant.

Gooseul, meanwhile, doubled as a dance trainer while navigating the band's schedule.

Members say things improved when a new label led by Kim Tae-hyun took over the group.

Kim’s own career has been turbulent. He worked as a manager of Im Chang-jung, a wildly popular singer-songwriter in the 1990s, and lost a hand in a car accident in 2002.

Since taking over Girls Alert in 2017, Kim said he has spent around 800 million won ($734,000) of his own money, which includes fees for the band's accommodation, van maintenance, hair and makeup, and a personal trainer.

In April, Kim — whom members describe as a father-like figure — asked the band members if they wanted to terminate their contracts and seek better opportunities elsewhere, as the coronavirus pandemic showed no sign of easing.

He didn’t ask for any penalty fees, which are often hefty and are frequently imposed by labels when band members try to depart.

Jisung said she asked Kim if he was abandoning the group, and refused to leave — a sentiment echoed by Gooseul and Seulbi.

Saetbyul and Narin elected to leave the band.

The pandemic has been a heavy blow to musicians around the world, but K-pop acts are more vulnerable, with many lacking the financial and social skills necessary to make ends meet. The majority of young performers spend nearly their entire adolescence — as long as 10 years — training and abiding by strict rules imposed by labels that often include strict dieting and rigid practice schedules.

Around 200 to 400 K-pop bands have debuted in the past decade, according to multiple South Korean media reports. With a success rate of less than 1%, it’s already a risky game, and with pressure from the pandemic, some lesser-known groups like Spectrum and NeonPunch have disbanded this year.

Despite the difficulties, Kim said he’s not ready to abandon hope on Girls Alert.

“If they don’t give up, I won’t give up,” he said.