Lawyer: Case of Black inmate set to die reveals racial bias

The lawyer for the first Black inmate set to die in a series of federal executions this year says race played a central role in landing him on death row for slaying a white couple from Iowa

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The lawyer for the first Black inmate scheduled to die this year as part of the Trump administration’s resumption of federal executions says race played a central role in landing her client on death row for slaying a young white Iowa couple and burning them in the trunk of their car.

One Black juror and 11 white jurors heard the 2000 federal case in Texas against Christopher Vialva, who is now 40 but was 19 at the time of the killings. Prosecutors portrayed Vialva as the leader of a Black street-gang faction and alleged he killed the deeply religious husband and wife, Todd and Stacie Bagley, to boost his status within the gang, attorney Susan Otto said.

But Otto contends there was no evidence Vialva, scheduled to be put to death Thursday, was even a full-fledged member — let alone a leader — of the 212 PIRU Bloods gang in his Killeen, Texas, hometown. She said the false claim only served to conjure up menacing stereotypes to prejudice the nearly all-white jury.

“It played right into the narrative that he was a dangerous Black thug who killed these lovely white people. And they were lovely,” Otto said in a recent phone interview. She added: “Race was a very strong component of this case.”

Questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system have been front and center since protests erupted across the country following the death of George Floyd after a white Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee on the handcuffed Black man’s neck for several minutes.

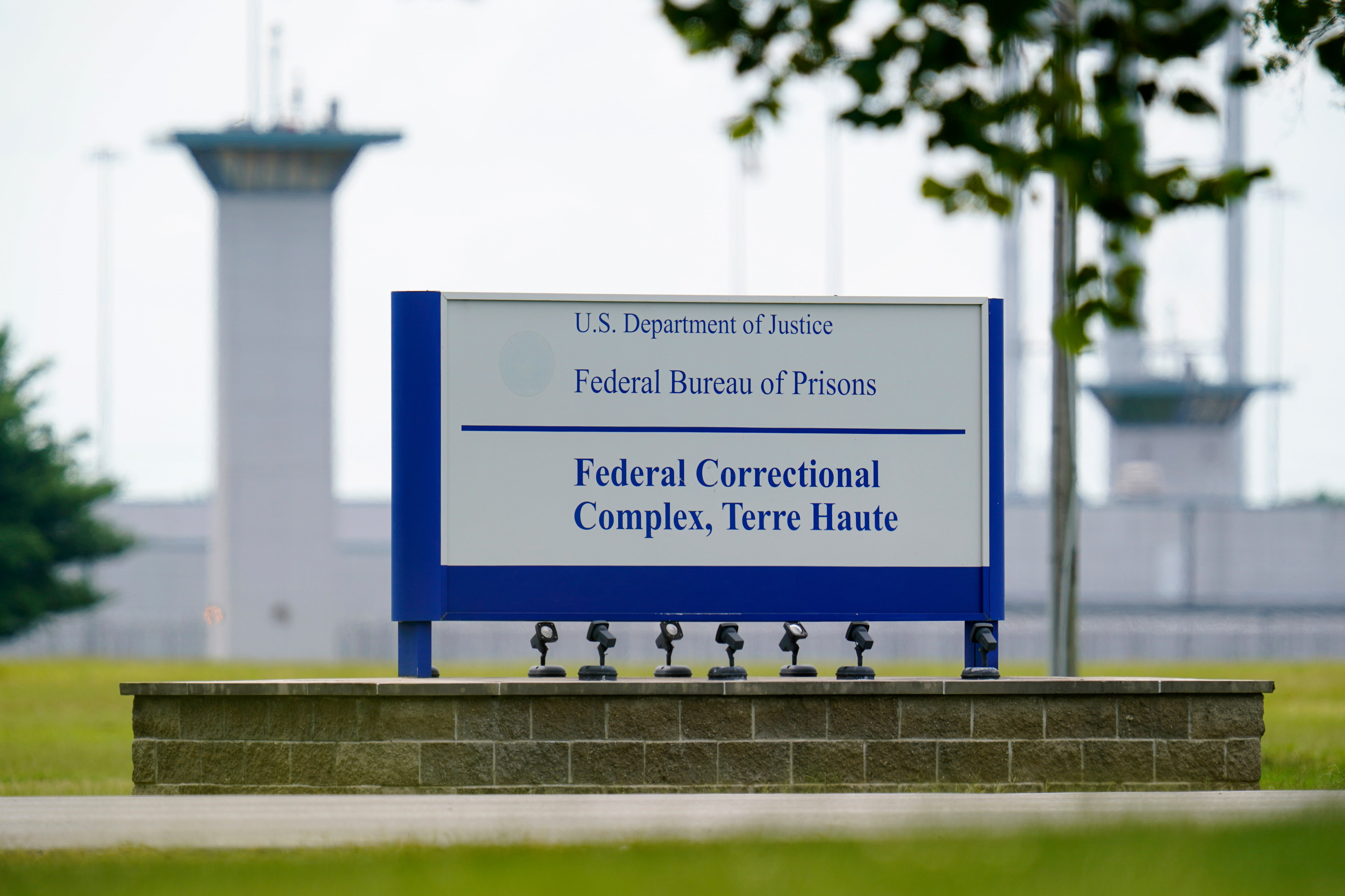

The Trump administration restarted federal executions this year after a 17-year pause, executing six inmates since July at the federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana — the most recent on Tuesday. Five of the first six were white, a move critics argue was a political calculation to avoid uproar. The sixth was Navajo.

A report this month by the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center said Black people remain overrepresented on death rows and that Black people who kill white people are far more likely to be sentenced to death than white people who kill Black people.

The focus of the report was on state death penalty cases, but the center’s director, Robert Dunham, said Wednesday there was ample proof the same problems exist at the federal level.

“The racial issues are the same as they are in state courts,” he said. “The federal system is not the gold standard for fair processes.”

Of the 56 inmates currently on federal death row, 26 — or nearly 50% — are Black, according to center data updated Wednesday; 22, or nearly 40%, are white and seven, around 12% were Latino. There is one Asian on federal death row. Black people make up only about 13% of the population.

Dunham says poor record keeping on federal and state death penalty cases makes it difficult to fully assess how much of a role race plays. Higher numbers of homicides in some minority areas, he said, also complicates analyses of death row disparities.

But he said studies have consistently demonstrated that race is a factor — to the detriment of Black defendants.

Vialva’s lawyers neither dispute the brutality of the crime nor his involvement in it.

According to court filings, the Bagleys were on their way home from a Sunday worship service during a visit to Texas when Vialva and his teenage accomplices asked them for a lift after they stopped at a convenience store — planning all along to rob the couple. After the Bagleys agreed and began driving away, Vialva pulled out a gun and told the couple: “Plans have changed.”

After stealing their money, jewelry and ATM card, the teens locked the Bagleys in the trunk of their car as they drove around for hours trying to withdraw money from ATMs and seeking to pawn Stacie Bagley’s wedding ring. The Bagleys pleaded for their lives from the trunk.

The teens eventually pulled to the side of the road and poured lighter fluid inside the car. As they did, the Bagleys sang “Jesus loves us” in the trunk. Vialva, the oldest of the group, donned a ski mask, opened the trunk and shot the Bagleys in the head. Stacie Bagley, prosecutors said at trial, was still alive as flames engulfed the car.

Vialva’s lawyers say the jury’s racial composition and prosecutors’ stress on alleged gang ties meant jurors were likely less open to mitigating factors, including Vialva’s difficult upbringing as a biracial child who faced racism in his own family. They say those factors should have led jurors to recommend a life sentence rather than death.

The overrepresentation of white people throughout the federal justice system, from judges to prosecutors, can also result in less empathy for Black defendants, Dunham said, as can the system of selecting Black jurors.

Jury pools in federal death-penalty cases involving Black defendants from inner cities are drawn from entire judicial districts, which span multiple counties that are often predominantly white. That, Dunham said, makes it less likely that the racial makeup of a jury will reflect a Black defendant’s community.

The U.S. Supreme Court as recently as 2017 sharply criticized any bids to hint that someone’s race or cultural background might mean that are prone to violence. Vialva’s lawyers say prosecutors did that by repeatedly referring to his supposed gang membership.

“The law punishes people for what they do, not who they are,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority in ordering a new trial for Duane Buck, who had been sentenced to death in a Texas double slaying after an expert called by his own lawyer said he was more likely to be dangerous because he was Black.

Roberts added that stereotyping Black people as more prone to violence is a “particularly noxious strain of racial prejudice.”

Otto said Vialva’s lawyers during the trial, the sentencing phase and in an initial appeal didn’t appear to raise objections about the racial composition of the jury or the characterization of Vialva as a Black gang leader. That effectively barred subsequent lawyers from raising the issue of racial bias in higher court appeals.

His current legal team has instead stressed Vialva’s level of mental development at the time of the killings. Otto said that Vialva was, developmentally, three or four years younger than his 19 years at the time of the killings and so for practical purposes was a juvenile at the time.

Otto says U.S. law doesn’t allow for judges to deem someone facing a possible death sentence to be technically a juvenile and therefore ineligible for the death penalty, something she says should change.

____

Follow Michael Tarm on Twitter: https://twitter.com/mtarm