How did so many miss the sinister warning signs about James Bulger’s killer for so long?

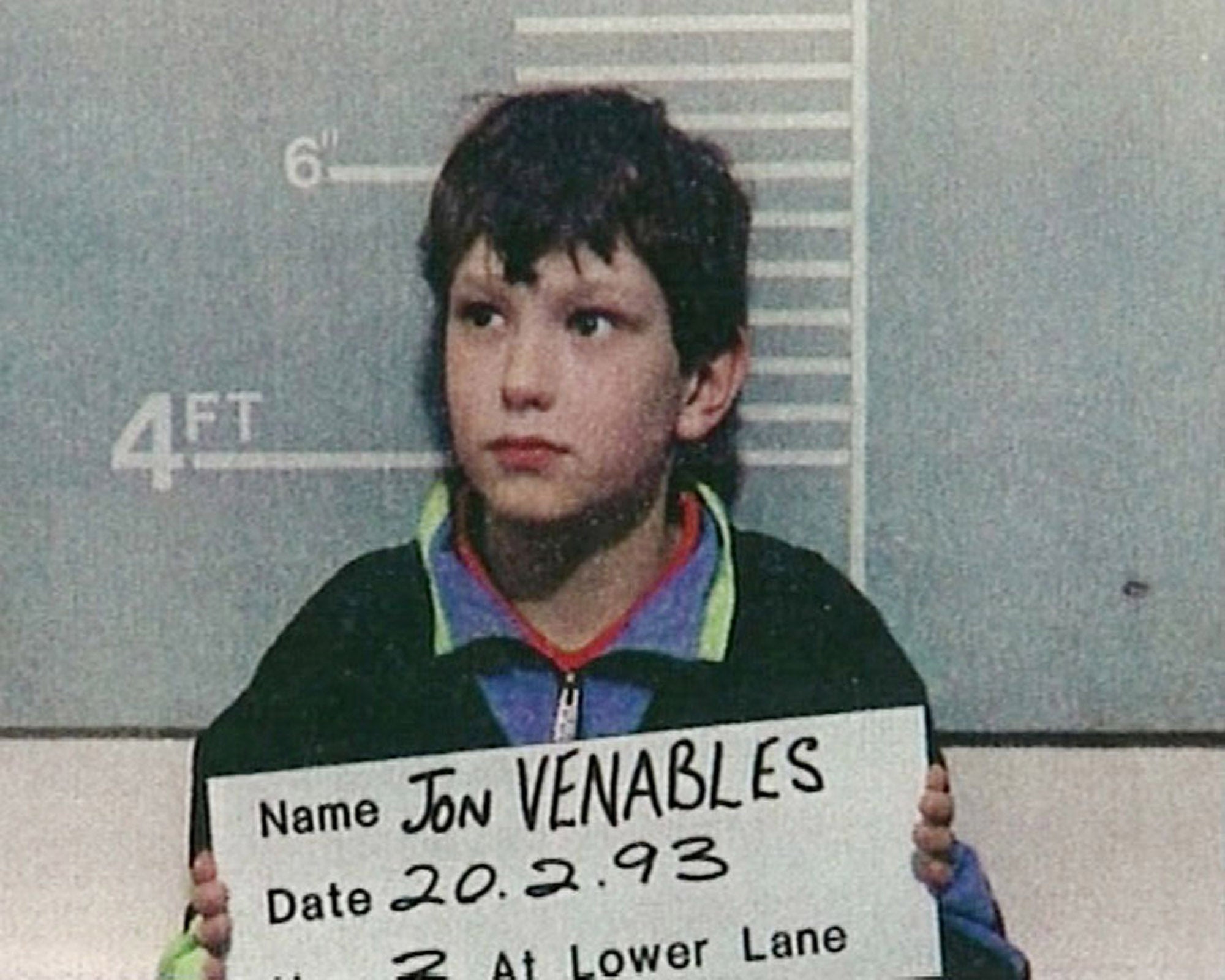

As Jon Venables is denied his bid for freedom because of his ‘long term sexual interest in children’, David James Smith - who has had access to his files and court papers over many years - asks why he was ever considered low risk to the public and a suitable case for parole

When did Jon Venables become a paedophile? And why? Those questions will have been at the heart of the Parole Board’s considerations in recent weeks – if not years – as they tried to determine whether he still poses a serious risk of harm to the public.

They are issues for Venables himself too. On Wednesday 13 December it was revealed that he has admitted to the board his “long-term sexual interest in children/indecent images of children”. The board acknowledged he had “completed a considerable amount of work in prison to address this area of risk”. It heard that some of the professionals working with Venables believed he was safe to be freed. But the panel assessing his case was still concerned by “continuing issues of sexual preoccupation in this case” and declined to release him agreeing there were “future risks” of him viewing indecent images of children and “progressing to offences where he might have contact with children”. He will remain in prison for the foreseeable future.

Venables’ sexual interest in children was first revealed in early 2010, in the most extraordinary circumstances, and purely by chance. He had been freed from eight years’ detention in 2001, for his role in the 1993 murder of two-year-old James Bulger, alongside Robert Thompson, when they were both aged 10. They had abducted James from Bootle Strand mall in north Liverpool, while his mother Denise was busy at a shop counter. They walked and carried him for two and a half miles, deflecting the attentions of numerous adults along the way, until they reached the little-used railway line at Walton, where they killed him during an assault with paint, batteries, bricks and a heavy metal plate.

By February 2010, around the time of the 17th anniversary of the murder, Venables was living alone, aged 27, with a new identity, in a flat in a northern town, some way from Merseyside. He was on life licence, under the supervision of a probation officer, who Venables called to say he thought his identity had been compromised, placing him at risk of public exposure and violent attack.

The probation officer contacted the police who rushed to make Venables safe. When they arrived at his home, with the probation officer looking on, the police found Venables trying to jemmy the hard drive out of his computer with a screwdriver.

The police seized the hard drive and searched it, finding dozens of indecent images of children. From his internet history they discovered that he had been online posing as a mother with a child she might offer for abuse by others. He was recalled to custody – going to an adult prison for the first time (he had served his sentence in Redbank, a secure unit for young people just outside Liverpool). He eventually pleaded guilty to three related offences and was sentenced to two years imprisonment.

The then lord chancellor, Ken Clarke, commissioned a former civil servant, David Omand, to conduct a “further serious offence review” and find out how Venables could have committed such crimes under the very nose of his probation officer and of an entire machinery of official scrutiny. Omand observed in his report that there was no doubt “his supervising officer and all the local police officers involved were shocked by the accidental uncovering” of Venables’ new offences.

Until that moment, no one had the slightest idea of Venables’ sexual interest in children. How could they have got it so wrong?

I have been writing, thinking about and commenting on the Bulger case for 30 years, since I went to Liverpool in the aftermath of the murder in early 1993; then sat, often uncomfortably, through the distressing evidence of the 17-day trial at Preston Crown Court later that same year. It ended, inevitably, with both children, Thompson and Venables, convicted of murder. Though both had denied it, there was never any doubt about their guilt – except perhaps a question about their childish understanding of what it means to take a life.

It was the received wisdom of the case then, and for many years after, that Robert Thompson was the thuggish leader of this little gang of two and Jon Venables merely the follower. I know that most of the police officers who dealt with them, including the senior investigating officer, Albert Kirby, believed that about the boy killers, as did many of the reporters and other observers who came to court.

But I always thought the evidence pointed in the other direction – that Venables had been more vocal and deceitful in their interactions with adults as they walked with James to the railway line. Certainly, the accounts of his primary school teachers suggested a little boy who had been very troubled and in need of help, from at least the age of seven.

It had once taken two teachers to pull him off another boy who he was trying to throttle with a 12in ruler. Fatefully, his behaviour was so concerning he moved schools – to the primary attended by Thompson. He was still only nine years old but his behaviour there was, if anything, even more disturbed: he sometimes used to stand in the playground and headbutt the wall.

Venables was the middle of three children; his siblings, were both diagnosed with learning difficulties and attended a special school. Meanwhile, his parents both appeared to struggle with their mental health and with the family challenges they faced. They had separated when Jon was four, and Jon and his brother had both been bullied by local children.

Obtaining access to some legal papers after the trial, I learned that Venables seemed deeply disturbed and remorseful about his role in the killing, and there was evidence of what was surely post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). During the trial he had been eager to remove his court clothes every day because he could smell “the baby smell” on them; he had asked if James was watching the trial from heaven and, in a powerful, disquieting vision, he had imagined a baby James growing inside him waiting to be reborn.

None of that, however, seemed to affect the assessments of Venables’ progress during his time at Redbank. There was no suggestion he might be suffering from PTSD. And, instead, staff reported him maturing into an amiable young man and becoming a role model for the other young detainees. His parents continued to support him, and he mixed openly with other young offenders as he pursued schooling and passed six GCSEs. He was separated from Thompson, who was in a different secure unit, Barton Moss, outside Manchester. In 1997, Venables’ therapist said he had made exceptional progress towards rehabilitation. By the time of his 2001 parole, it was being claimed he posed a “trivial” risk on release.

There had been speculation at the time and since about the highly sensitive issue of a sexual element to the killing of James Bulger. The Parole Board considered this during its recent review. There was some suggestion that a battery might have been inserted into his anus and that his foreskin might have been touched, but neither of these claims were fully supported by the evidence and both were denied by the two boys.

An unnamed psychiatrist who worked closely with Venables over the years, reported that “at no time during sessions has Jon presented with any evidence of any prior or current abnormality in psychosexual development or of any sexualised component of the offence. Visiting and revisiting the issue with Jon as a child and now as an adolescent he gives no account of any sexual element to the offence”.

Omand said he had read all the reports and “found no suggestion that there was a sexual motive on the part of Jon Venables in committing the original offence or other warning that might have alerted the Board to potential abnormal sexual interests”.

As the Omand review later recorded, a leading psychiatrist told the 2001 Parole Board hearing that there was a good likelihood Venables “should be able to make a success of the rest of his life. However that likelihood would be greatly affected by the availability of high-quality rehabilitation over the period ahead during which he readapts to society. The chances of successful rehabilitation are very high”. But that judgement was strictly contingent on further rehabilitation and on his identity being protected. Venables and Thompson, now both aged 41, are among a handful of people in this country whose whereabouts and identities are protected by lifelong court injunctions.

When Venables was re-released, following his imprisonment for the indecent images offences, in November 2013, he was subject to even greater controls, a Parole Board decision that meant it believed his risk to the public was manageable. But again he began secretly hoarding indecent images of children, this time much of it more extreme and in greater quantity. In 2017, the new material was discovered on his computer and again he was recalled to prison and charged. Venables had 1,170 images and videos, 320 of them in category A showing the most extreme assaults on children and babies. In February 2018, five days before the 25th anniversary of James’s death, Venables entered guilty pleas to four offences and was imprisoned for three years and four months. He has remained in prison ever since.

The 2018 sentencing judge at the Old Bailey, Mr Justice Edis, noted that the killing of James Bulger “was a crime which revolted the nation and which continues to do so” even after a quarter of a century.

He set out in some detail Venables’ latest crimes which included using an anonymous browser in an attempt to hide his downloading of child pornography. He had also acquired a “paedophile manual” which the judge described as “a vile document which gives detailed instructions on how to have sex with children, as it puts it, ‘safely’”. The judge made a direct link with James Bulger’s murder. “Given your history”, he told Venables, who appeared from prison by video link, “it is significant that a number of the images and films were of serious crimes inflicted on male toddlers.”

Edis acknowledged that there was no evidence Venables had ever yet sought direct access to children or embarked on any grooming behaviour. But he said the possession of the manual suggested Venables was “at least contemplating the possibility of moving on to what are called ‘contact offences’”.

Set alongside the indecent images, Edis said, it suggested he had “a compulsive interest” in serious sexual crime against children which, given the “very great risk" he had taken in committing the offences, appeared to be a compulsion that Venables could not control.

No doubt the Parole Board will have paid attention to the judge’s pointed remark that they would consider Venables’ future release with particular care, taking account of information (he did not say what it was) in the pre-sentence report he had read. The author of the report had concluded that Venables presents “a high risk of serious harm to children”.

At this stage, it is difficult to see how Venables will ever be able to show that the risk he poses can be managed or mitigated. But what are the origins of his sexual interest in children and how far back does it go? And how could all the experts have been so wrong in their assessments of him? While Thompson blended back into society after his release, and has never been heard of since, Venables’ life descended into chaos and criminality, breaching his licence, being caught with cocaine, getting into a drunken fight and finally being exposed as a paedophile.

When I first began trying to piece this history together, after Venables was recalled and sent to prison in 2010, I discovered that, in fact, the Omand report had failed to mention a potentially significant incident, during Venables’ adolescence when he had a brief sexual relationship with a female member of the Redbank staff. There was no criminal prosecution of the staff member when the incident was discovered but they were suspended and never returned to work there.

However much Venables subsequent crimes have been reviled, he was a vulnerable teenager at that time; the victim, not the perpetrator, in that incident.

Indeed it seemed likely that this may not the only secret that Venables may have kept hidden over the years he was at Redbank, and afterwards. His behaviour could be the result of abuse or mistreatment that he himself possibly experienced at some point in his young life.

If so, he must have buried those experiences throughout his years of detention, kept them hidden from the psychiatrists, therapists and trained staff who supported him, just as he later hid his paedophile activities from his probation officer. You can see the origins of this manipulative and deceitful behaviour in his conduct during James’s abduction and killing, and even further back, during his primary school days. One teacher who saw Venables cutting himself with scissors and generally being disruptive in her classroom said she had never seen such troubling behaviour in 14 years of teaching.

Now he has admitted to the board that he has a long-term sexual interest in children, maybe there will be some piecing together of the reasons he was so disturbed . Venables’ own prospects of any future freedom, his own safety and the safety of the public, will surely now depend on bringing many years of hiding and deceit to an end. Only he knows the truth – whether we will ever know it will now be up to him.

‘The Sleep of Reason: The James Bulger Case’ by David James Smith

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments