Why James Bond will be up against a new electrifying villain: ‘Licensed to kill, sustainably’

Britain is poorly served for locations where electric car drivers can recharge their batteries. Something for 007 to consider during his next death-defying chase, suggests Wolf Ingomar Faecks

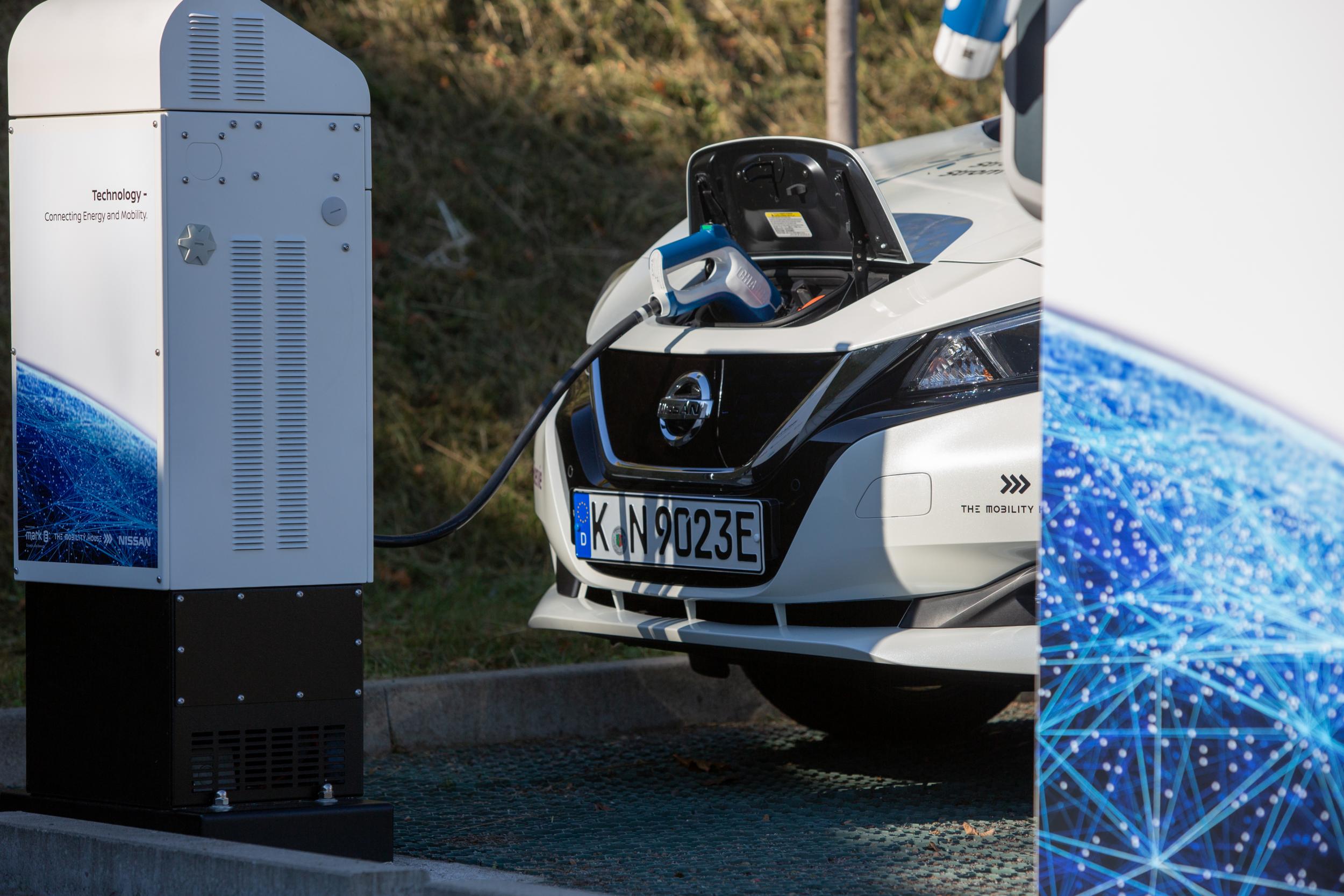

“Licensed to kill, sustainably” is perhaps not as ringing a catchphrase as the original, but it may be the reality with reports that in his next movie, James Bond will be driving an electric Aston Martin. Agent 007 isn’t the only one making the move to the greener alternative, however. There are currently around 4 million electric vehicles on roads globally, and the International Energy Agency predicts there will be 300 million by 2040. But James Bond is British, and he’s going to face one key problem: running out of charge.

In the UK, the infrastructure for electric cars is simply not up to supporting Bond on a cross-country car chase. From a lack of charging stations to a total inability to provide the kinds of power necessary for charging-at-scale, the UK is not where its leaders would like to think it is in terms of leading the conversation on uptake of new automotive technologies.

While Bond might have some luck with his Aston Martin Rapide E in Cornwall or Milton Keynes, which tend to have fewer than 2km between charging points, he’d better hope the bad guys he’s chasing avoid Oxford or Norwich, where, if his battery ran low, he’d be looking at lugging his car 6 to 10km before he could give it some gusto. This illustrates the key problem: there’s a huge disparity between local authorities and their electric car charger provision, and there’s barely any attempt to address the problem in a comprehensive approach.

Over a third of local authorities in Britain have fewer than 10 locations where drivers can recharge their car batteries, according to the RAC, while only three had more than 100. While the government has offered councils part of a £2.5m funding pot to improve their network, only 28 have even applied.

The need for alignment goes beyond building charging stations, however – we also need to provide them with power. If you consider a world in which we own electric cars at scale, we’ll need charging stations where we can sit 10 or 20 cars to charge in parallel. Our current cables simply cannot support that with current voltage limits – and while the Department for Transport is quick to point out that 80 per cent of electric vehicle owners charge them at home, many homes don’t have enough bandwidth to charge more than one car. And going further, those consumers living in apartment blocks with a communal garage won’t have access to charging unless infrastructure can be adapted to allow those buildings to provide the kind of power needed.

The problem is that the industry is locked into a game of chicken and egg. There’s a reluctance to produce too many of these vehicles, and in turn consumers are reluctant to buy them. This industry nervousness is compounded by limitations of the technology, fears around the “Uberification” of the market and what the sharing economy might mean for car ownership and, more widely, the conditions of the economy. For example, nobody knows what Brexit will mean for the automotive industry. Given that most cars are imported, there’s likely to be an impact on price, which might also impact how many units are being sold – slowing down the rate of electric uptake.

The UK can’t sit back and hope for the best – it needs to align interests of local authorities, government and private businesses to ensure that there’s a master plan in place.

There’s a lot that could be learned from the Netherlands in this regard and its “Green Deal” initiative. This aims to stimulate sustainable innovation by providing a way for private businesses, educational institutions, local and regional governments and interest groups to work with the national government on green growth and social issues. Essentially, if an individual or business is facing barriers to a sustainable innovation, the government works to remove any legislative barriers to that. It has meant that their infrastructure has developed a lot faster, and with it, sales. In 2018, sales of electric vehicles tripled.

Without a more serious attempt to align businesses, startups, innovators and local authorities from the government, the UK – so desperate to be seen as techy, innovative and keen for an acceleration of electric vehicle uptake – will fall behind. And James Bond will have to have his next adventure in Holland.

Wolf Ingomar Faecks is managing director and transportation industry lead at digital agency Publicis Sapient

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks