Alcohol 'hijacks' the brain to impair memory and cause long-lasting cravings, study suggests

Single drink can affect memory formation for hours with critical changes in the reward centres which reinforce positive behaviours

A single molecular change could help explain why a few glasses of wine can impair your memory for days and why alcoholics are liable to relapse after decades of abstinence, scientists have said.

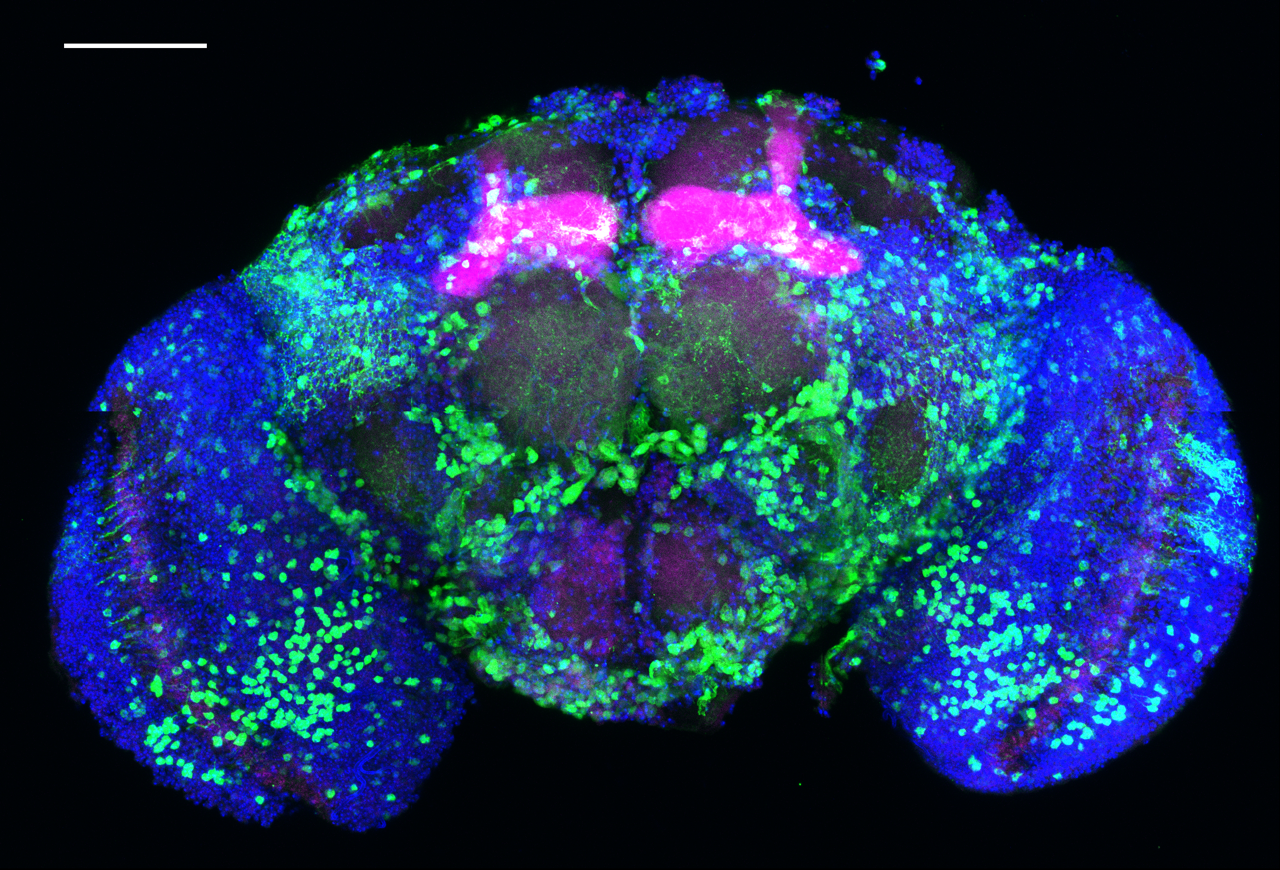

US neuroscientists using fruit flies to understand the chemical levers that alcohol pulls in the brain have found a new way it changes regions linked to positive experiences and cravings.

While flies have just 100,000 neurons to the 100 billion in humans they share some core features, and one of the shared areas disrupted by alcohol is key to the way animals learn to chase rewarding experiences.

This could help explain why the harms of alcohol, from hangovers to more serious issues associated with addiction, are discounted by addicts, researchers from Brown University researchers said.

“All drugs of abuse – alcohol, opiates, cocaine, methamphetamine – have adverse side effects. They make people nauseous or they give people hangovers, so why do we find them so rewarding?” said lead author Dr Karla Kaun, an assistant professor of neuroscience.

“My team is trying to understand on a molecular level what drugs of abuse are doing to memories and why they’re causing cravings.”

The prolonged effect they identified in flies, if found in humans, could explain why alcohol abuse “hijacks” these positive associations and forms a lasting craving in recovering alcohol addicts.

By studying flies hooked on alcohol the Brown researchers were able to monitor the nerve pathways and genetic signals that lit up when they had cravings.

One key system was a group of cellular mechanisms which play a crucial role in the development of the brain and nerve system of all animals, including fruit flies and humans, known as the “Notch” pathway.

In the cell, Notch works like a chain of dominoes, beginning with an initial Notch receptor which when activated sets off a chain of other cellular processes.

In the developing embryo it helps signal when it’s time to start forming the brain, but it has an “underappreciated role” in adults in the formation of memories, Dr Kaun and her co-authors said in the journal Neuron.

In flies addicted to alcohol they found exposure led to changes further down the Notch cascade. One change, is in a single building block of a large receptor molecule on nerve cells which helps detect a chemical called dopamine, also known as the “feel good” neurotransmitter.

This dopamine receptor “is known to be involved in encoding whether a memory is pleasing or aversive,” the authors said.

“If this works the same way in humans, one glass of wine is enough to activate the pathway, but it returns to normal within an hour,” Dr Kaun added.

“After three glasses, with an hour break in between, the pathway doesn’t return to normal after 24 hours. We think this persistence is likely what is changing the gene expression in memory circuits.

“Just something to keep in mind the next time you split a bottle of wine with a friend or spouse,” she added.

She added that this is “highly likely to translate to other forms of addiction” if it does hold true in humans.

Researchers not involved with the study said the fact that they had identified changes at the molecular level could also lead to new treatments for addiction.

“Alcohol hijacks brain processes that allow us to remember things for a very long time,” Professor Peter Giese, a mental health neurobiology expert at King’s College London, who was not involved with the study, said.

“[This study] suggests that drug addiction persists because memory mechanisms were hijacked by drug exposure.

“The study not only provides a model for understanding the persistence of drug addiction, it also identifies potential pharmacological targets for treating addiction.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks