3D-printed blood vessels could improve heart bypass outcomes, research suggests

A team led by experts at the University of Edinburgh produced the vessels, and hope to now test their theory in animals.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.3D-printed blood vessels which closely mimic the properties of human veins could transform the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, scientists have said.

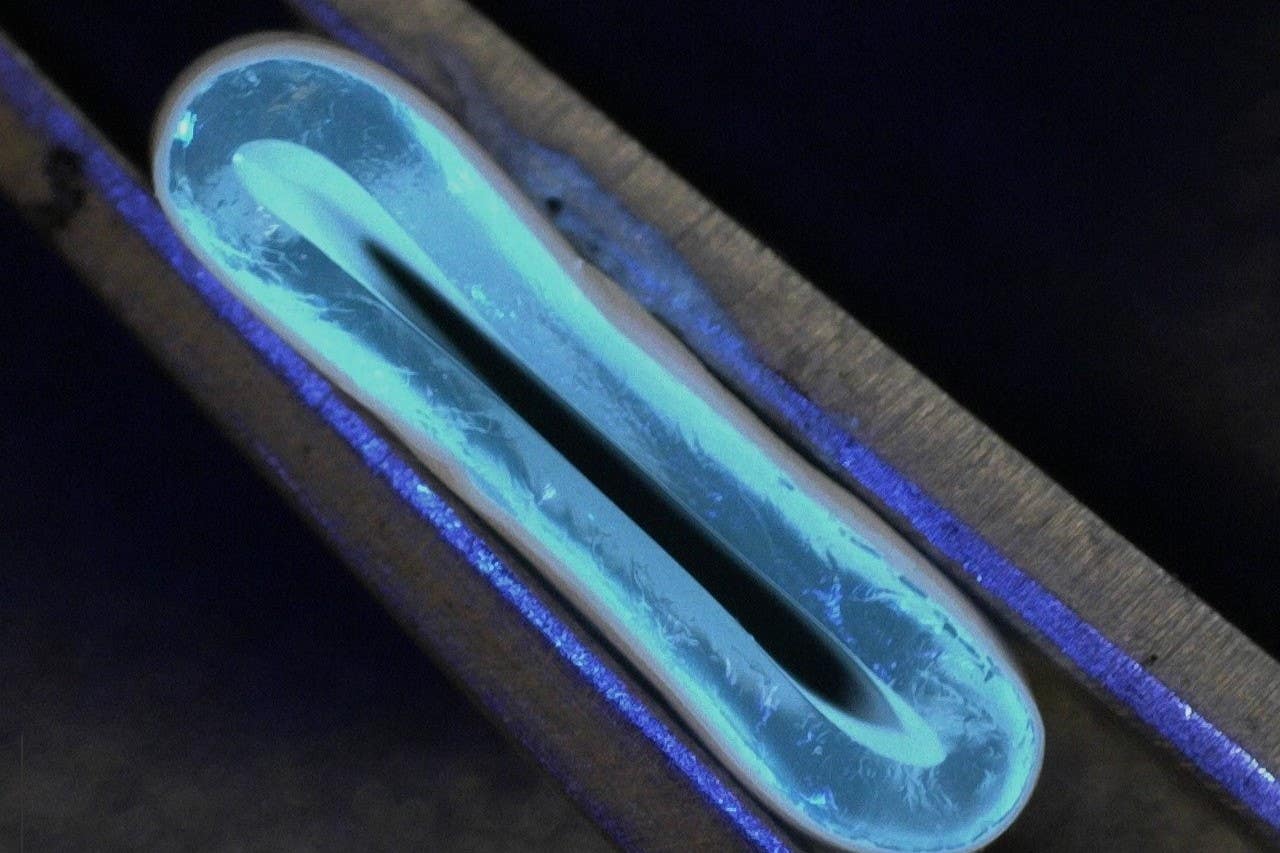

A team of researchers led by the University of Edinburgh School of Engineering produced the synthetic vessel from a water-based gel, using a 3D printer with an integrated rotating spindle.

Next they reinforced it with a process called electrospinning, which uses high voltages to draw out thin nanofibres, coating the tube in biodegradable polyester molecules.

The team said the flexible, gel-like tubes, which are as strong as natural blood vessels and easily integrated into the body, could replace the human and synthetic veins that are currently used to re-route blood flow in heart bypass operations.

According to the researchers, this could limit the scarring, pain and infection risk associated with the removal of human veins in the 20,000 heart bypass operations performed each year in England alone.

With continued support and collaboration, the vision of improved treatment options for patients with cardiovascular disease could become a reality

The team said the tubes, which can be made between 1mm and 40mm in diameter, could reduce the failure of small synthetic grafts which can be hard to integrate into the body.

Lead author Dr Faraz Fazal said: “Our hybrid technique opens up new and exciting possibilities for the fabrication of tubular constructs in tissue engineering.”

Principal investigator Dr Norbert Radacsi said: “The results from our research address a long-standing challenge in the field of vascular tissue engineering – to produce a conduit that has similar biomechanical properties to that of human veins.

“With continued support and collaboration, the vision of improved treatment options for patients with cardiovascular disease could become a reality.”

The next stage of the study will involve researching the use of the blood vessels in animals, in collaboration with the university’s Roslin Institute, followed by trials in humans.

The research, published in Advanced Materials Technologies, was carried out in collaboration with Heriot-Watt University.