World's first test tube baby at 40: How the public reacted to the IVF breakthrough of the century

Birth of Louise Joy Brown in Oldham on 25 July 1978 met with huge press interest, poison pen letters and concern from the Vatican

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Louise Brown, the world’s first “test tube baby”, celebrates her 40th birthday on Wednesday 25 July.

Her parents, Bristol railwayman John Brown and wife Lesley, had been trying to conceive for nine years without success when they encountered Oldham-based obstetrician Dr Patrick Steptoe and his research partner, Cambridge physiologist Dr Robert Edwards, in 1977.

Steptoe and Edwards had been working with Jean Purdy in the experimental field of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and successfully implanted an embryo into Ms Brown – from a petri dish, rather than a test tube – on 10 November of that year, making headlines around the world.

Nine months later, a healthy baby girl named Louise Joy Brown was born via a planned caesarean section at Oldham and District General Hospital, weighing five pounds and 12 ounces.

The public reaction to this breakthrough fertility treatment and the “baby of the century” was decidedly mixed, however.

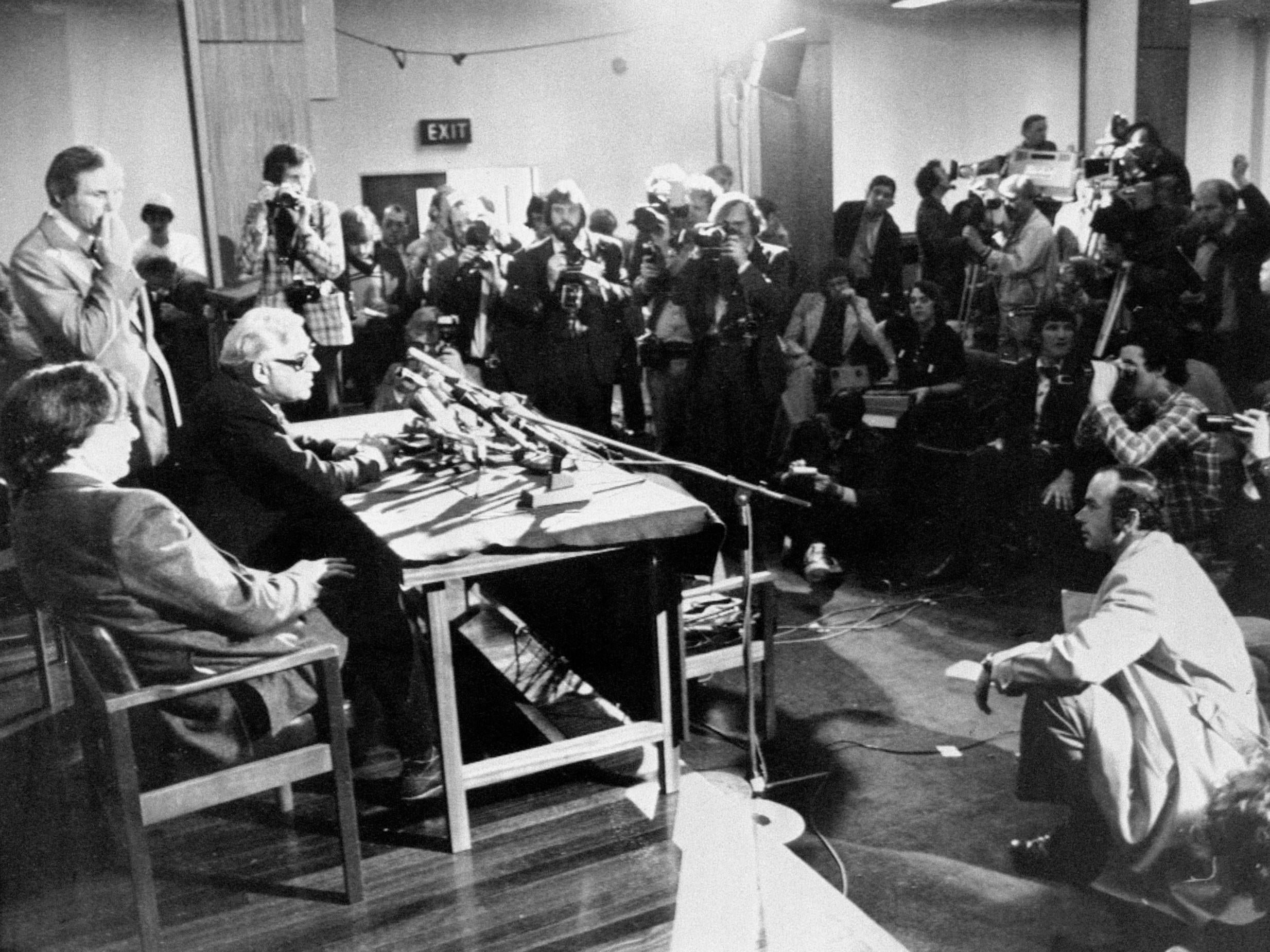

Tabloid hacks questioned the advent of “Frankenbabies” and sent enough paparazzi to Oldham to spark a bomb scare, causing the evacuation of the hospital.

The institution’s corridors were lined with police officers as John Brown arrived to meet his daughter for the first time.

When the new family arrived home in Bristol together, 100 reporters blocked the streets. Curious local children were also out in force, including seven-year-old Wesley Mullinder, who would grow up to be a nightclub bouncer and Louise’s husband, their wedding in 2004 attended by Dr Edwards.

As she would later write in her memoir, Louise Brown, my life as the world’s first test tube baby (2015): “My birth seemed to bring out the worst in all the journalists. This was hardly a story that needed sensationalising.”

The Vatican expressed its anxiety at the news, with Cardinal Albino Luciano (soon to be the short-lived Pope John Paul I) telling the press from his hospital bed in 1978 that he had no right to condemn the parents for desiring a child of their own but warned that doctors, like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, might find themselves struggling to contain the consequences of their actions.

He also argued that not all scientific advances are for the good of humanity, pointing to weapons of mass destruction.

The Browns received huge quantities of letters and packages over the coming months from interested members of the public, much of which Ms Brown kept as mementos.

Some of this was warm and congratulatory, the rest hate mail of a particularly vicious stripe, as Louise, now a shipping clerk, Take That fan and mother of two, has since recalled in her autobiography.

One parcel was addressed to “Louise Brown, Test Tube Baby, Bristol, England” and had been posted from San Francisco: “Inside, Mum found a small jewellery-style box with the words ‘Test Tube Baby’ printed on a sticker with an image of some baby footprints.

“She thought maybe it was another gift from a corporate anxious to be associated with my birth but when she opened it there was red liquid that looked as if it had spilled and a carefully folded letter.”

It also contained a broken glass test tube and a plastic foetus.

“It was menacing and scary and considering the time the people must have taken in putting this thing together then sending it across the world to a three-month-old baby, I would say a completely sick act by some sick minds.

“Imagine how worrying this was for Mum... For a while, she was even more careful when taking me out in the pram.

“[There was] a lot of Catholic objection – and apparently I could read things with my mind and teleport stuff,” she recalls.

At primary school, Louise’s fellow pupils knew about the sensation her birth had caused but struggled to comprehend the science behind it.

“I’ve always been a bigger girl and they used to say: ‘How did I fit in the test tube?’”

Living in the public gaze put a strain on the family but Lesley Brown felt an obligation to share her miracle baby with the world.

Louise likewise routinely takes time out from her job to attend fertility conferences around the world and spoke at the European Parliament on access to IVF in February 2017.

Astonishingly, four decades on, she is still receiving abuse and harassment, with online trolls replacing the anonymous poison pen authors of the past.

“People put cruel and ill-informed comments on the internet just about whenever there is a story about me. But I just ignore it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments