Statins could be used to fight prostate cancer, new research suggests

Study ‘first of its kind to show statins having a detectable effect on prostate cancer growth in patients’, says lead researcher

Drugs commonly used to reduce cholesterol could one day help to treat prostrate cancer, new research suggests.

A clinical trial with 12 patients, conducted at the Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre in Glasgow, found that statins slowed tumour growth when given alongside androgen deprivation therapy, a treatment that reduces male hormone levels.

Professor Hing Leung, who led the research, said the study was the “first of its kind to show statins having a detectable effect on prostate cancer growth in patients”. Each year, around 52,300 people are diagnosed with prostate cancer in the UK, figures suggest.

Prof Leung said: “We think statins could stop prostate cancer from making androgens [sex hormones] from cholesterol, cutting off a route for cancer to resist androgen deprivation therapy.

“Castration-resistant prostate cancer, when cancer becomes resistant to hormone therapy, is currently very difficult to treat. If further trials are successful, we could use these already approved medicines very quickly to offer patients better options for treatment.”

Prostate cancer requires androgens, such as testosterone, to grow. Existing treatments reduce androgen levels in an attempt to stop the cancer from growing. However, in some cases prostate cancer can become “castration resistant”, meaning it stops responding to these treatments.

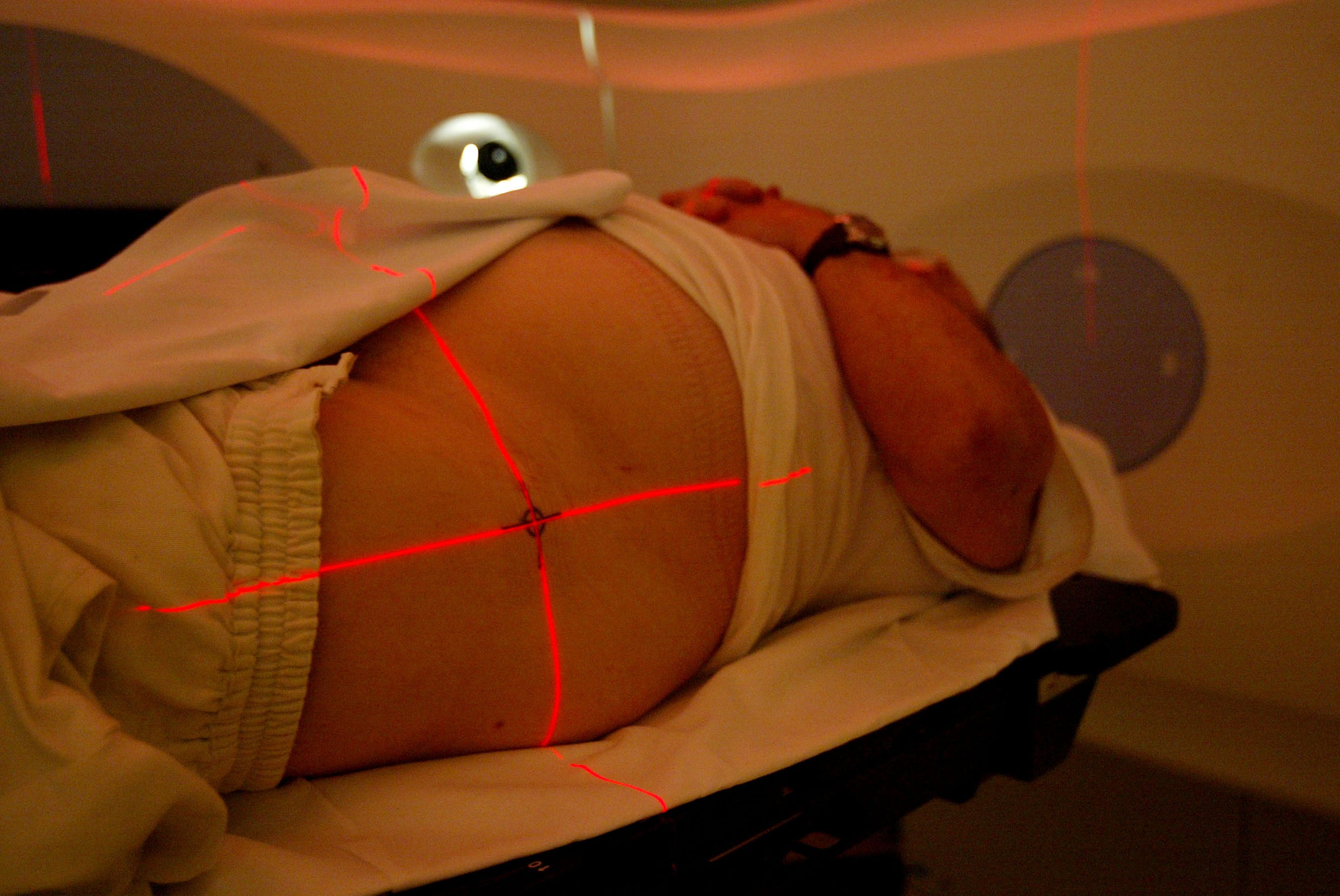

Over a six to eight-week period, the researchers gave atorvastatin to 12 patients whose cancer had become resistant to this type of therapy.

The team then measured levels of prostate specific antigen (PSA), which is used to estimate tumour growth in patients with prostate cancer, and found 11 out of the 12 saw their PSA levels fall while taking atorvastatin.

The researchers are now hoping to launch a larger study to determine if statins could be used more widely to treat prostate cancer.

Dr Hayley Luxton, a senior research impact manager at Prostate Cancer UK, said: “We are pleased to have funded this study, which shows encouraging early signs that statins could help slow prostate cancer growth.

“Further research is now needed to understand the best time to add statins to prostate cancer treatment, and to test this approach in a much larger group of men.”

The findings of the study have been welcomed by John Culling, 64, who was diagnosed with an aggressive form of prostate cancer in 2019.

John, who lives in Broughty Ferry near Dundee with his wife Margaret, underwent chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone treatment, which was successful, and he is now being monitored.

The father of two said: “The aggressiveness of the prostate cancer I have means there is a high chance it could come back, so it’s a case of waiting and watching.”

A former captain in the army, John is hopeful the current research will be further developed to help treat the disease even more effectively in the future.

He said: “Knowing that scientists are working in labs and hospitals conducting research and clinical trials, especially with drugs that are already in use for other conditions, gives me hope both for myself and for future generations.

“Hopefully, research like this means even better outcomes for anyone who might have to go through a diagnosis like mine.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks