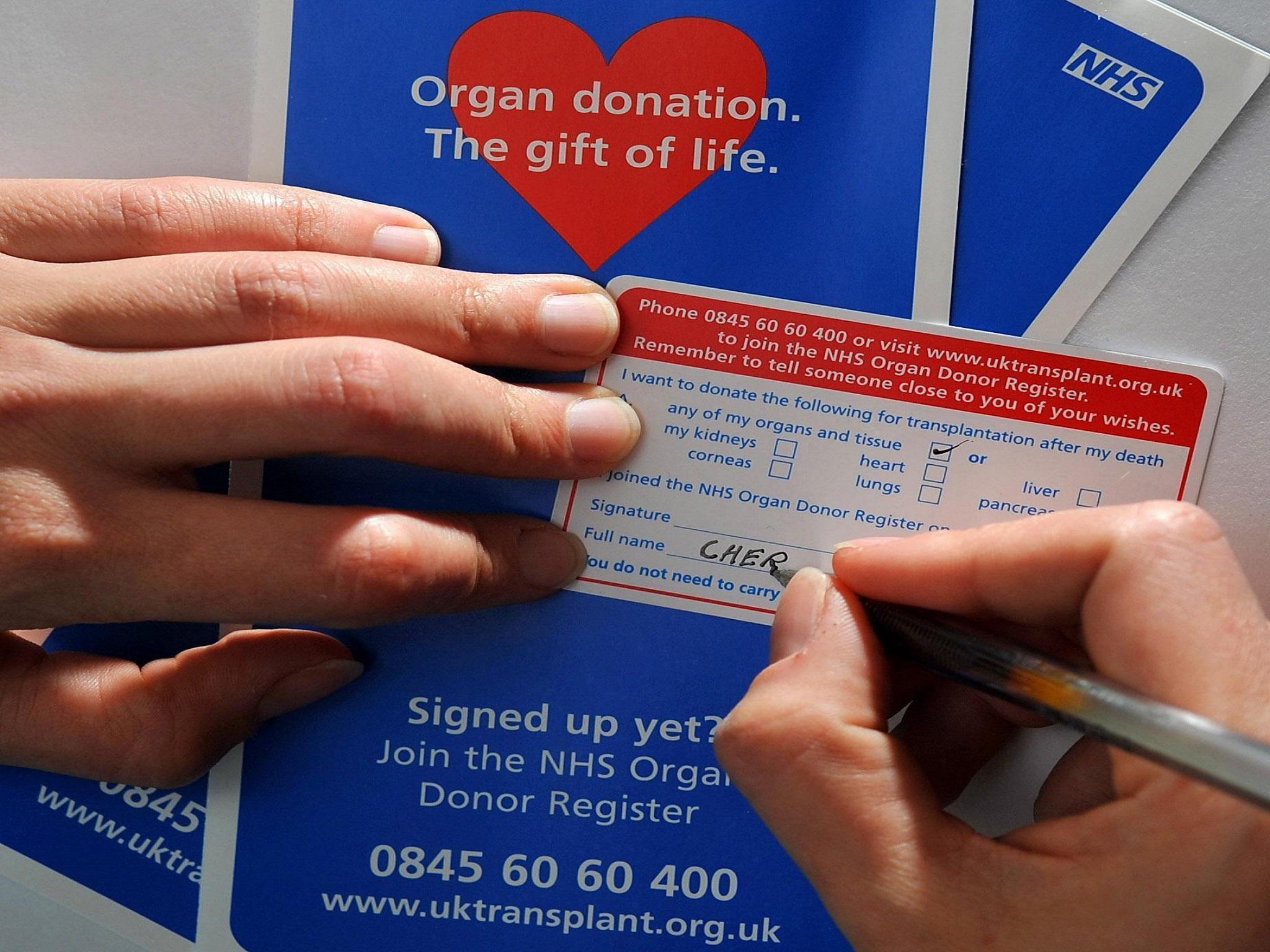

Organ donation consent law change could 'undermine' public trust, ethics experts warn

Nuffield Council on Bioethics plan to make everyone a donor unless they object is not backed by the evidence and could mean fewer transplants

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Medical ethics experts have called for caution as a proposed change to organ donation laws in England, which would make everyone a donor unless the explicitly register an objection, made the first step to becoming law today.

At the 2017 Conservative Party Conference Theresa May announced the bid to “save thousands of lives” by increasing the number of donors and removing the need for donor cards.

A bill debated today claims the change to a “presumed consent” system would save 500 lives a year; however, experts from the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCB) warned that the claim is not backed by evidence and risks undermining public trust.

Data from Wales, which introduced presumed consent in 2015, shows it has not increased organ donations so far and organ transplants dipped – from 214 to 187 – between 2015-16 and 2016-17.

The NCB says, on its own, the scheme might make people more reluctant to donate.

Without clear evidence ministers should instead focus on factors which have been proven to work, such as training nurses to discuss donation with bereaved families and raising public awareness.

“We fully endorse the aim of increasing the rate of donated organs, but we are concerned that making a legislative change based on poor evidence risks undermining public trust in the organ donation system, and could have serious consequences for rates of organ donation,” NCB director Hugh Whittall said.

Nearly 6,500 people in the UK are waiting for a transplant, but hundreds die on the list each year.

In the UK donations can typically only take place with a loved one’s consent, as even when a person is a registered donor 1,200 families a year refuse to allow donation.

MPs backed the new “soft opt-out” organ donation bill at a second reading, the first opportunity for debate after a bill is proposed, in the House of Commons today.

The bill would not apply to anyone under 18 or unable to give informed consent, and a public consultation is underway to determine any other safeguards that are needed.

Labour first proposed changing to an opt-out system in their election manifesto and Jeremy Corbyn urged MPs to back the bill.

He said on Twitter: “The gift of life is the most precious thing we can give. The time has come to change the law.”

Health and Social Care Secretary Jeremy Hunt also backed the bill “as a first step towards the life-saving reforms we need”, citing the case of recent transplant beneficiary, former footballer Andy Cole.

The former England and Manchester United striker underwent a kidney transplant at Manchester Royal Infirmary in April last year, after developing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

Labour MP for Sunderland Central Julie Elliott gave a speech in support of the bill after her daughter Rebecca, 36, developed a serious kidney problem in October 2016 and is now on dialysis.

“What happened to us over the last 18 months could happen to anyone, rich or poor, young or old there’s no differentiation when this type of thing happens, and it highlights the need to change the law to a position of deemed consent.

“The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease came as a huge shock, to Rebecca, to me, our family and friends.

“To face the reality of the fragility of life is very hard at any time, but to face it about one of my children, although an adult, is one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to face.”

Spain is seen as a “gold standard” model for organ donation and the NCB said its success was based on better systems for getting donor organs to patients who need them in time, and respecting the wishes of families.

While Spain has an opt-out law no register of opt-outs is kept and the director of the Organizacion Nacional de Trasplantes has called the presumed consent system a “distraction”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments