‘How many more are there?’ Grieving parents call for action as they tell their stories of tragedy

Warning: Some readers may find the images below distressing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

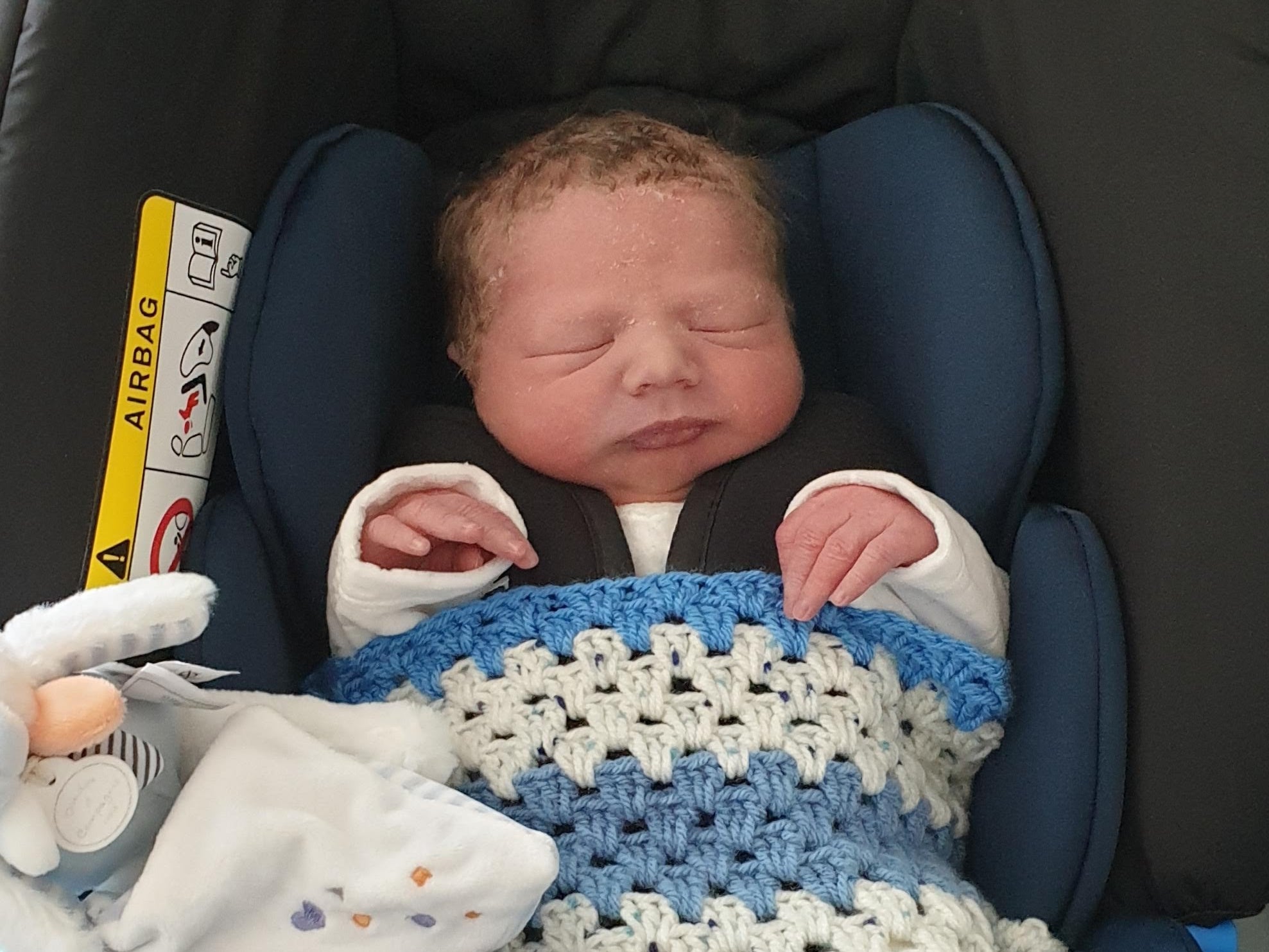

Your support makes all the difference.In his car, Chris Lewin still has the children’s book that he read to his dead son in the bereavement suite at Nottingham hospital four years ago. He takes the book, Guess How Much I Love You by Sam McBratney, sometimes when he visits Freddie’s grave, sitting to read the book to his son once more.

Freddie died shortly after a chaotic birth in February 2017 when staff at the city’s Queen’s Medical Centre left mum Naomi on her own, failing to recognise she was actively giving birth until one of Freddie’s legs was spotted.

The infant was a premature breech birth at almost 27 weeks and became trapped. His throat was accidentally cut by doctors with scissors during the delivery. Extensive injuries included severe bruising that blackened his leg from hip to toe. Chris, 34, recalls a junior doctor “pulling on both legs … they were basically just yanking parts of him out.”

His case is just one of dozens in which babies at Nottingham University Hospitals Trust died or were severely injured after errors in care. The families say that, if lessons had been learnt from each of these tragedies, more lives could have been saved.

Chris and his wife Naomi, 27, believe photos of Freddie showing a droop on his left side of his face are proof he suffered a fractured skull, and are adamant he had broken bones in his legs and arms.

Have you been affected by poor maternity care? Email: health@independent.co.uk

The couple, who also have four daughters, say they could hear their son’s bones breaking as doctors struggled to deliver him.

“I could hear the noise as they were yanking on him to get him out,” Chris said: “It shot through me then and if I think about it now, I can still hear it.”

The trust says Freddie’s death was reported to the Nottinghamshire coroner, but doctors did not document the details of the discussion. A death certificate was issued without a post-mortem examination.

While Chris and Naomi were in the midst of their grief hours after Freddie’s death, they were asked if they wanted an autopsy. At the time they wanted to spend time with their son and refused – a decision the hospital has now used against them as no definitive evidence of injuries to their son was documented.

An investigation later concluded that discussions with the coroner and consideration of a post-mortem examination had not been sufficiently documented.

Chris and Naomi say the medical records of what happened that night are wrong despite remembering staff taking notes: “Those notes don’t seem to exist. Half of what happened during Freddie's birth isn’t there, there was just one paragraph. None of the things they were done to get Freddie out is there. It seems to me like a lot of very valuable information magically disappeared.”

Chris asked that Freddie be left alone so he could wash and dress the infant, but staff later brought Freddie fully dressed, a move Chris believes was an attempt to hide what had happened.

“It wasn’t until I undressed him that I started seeing the damage,” he said. A doctor who assessed Freddie claimed his injuries were normal for the type of birth, but his findings were not documented. The trust investigation concluded there were “traumatic injuries” to Freddie but the extent could not be verified without a post-mortem. It accepted the timing of that discussion with the Lewins “was not ideal”.

Chris said: “It was bad enough in the first place, but the way they’ve dealt with everything since then has made it four or five times worse than it needed to be. All we wanted throughout the whole thing was a bit of honesty from somebody.

“Freddie paid the ultimate price for everything they did wrong. That brief period of his life, he lived through hell. And they haven’t changed anything.”

‘He is my son and I want answers’

For Dave Needham the horror of feeling his son’s chest and realising he was cold and no longer breathing is as fresh today as it was when his son, Kouper, passed away in July 2019, just hours after being allowed home from hospital.

His wife Natalie had to perform CPR on her own child as paramedics rushed to their home in Nottingham and the couple believe what happened to their son was a result of a failure by staff at the hospital to listen to their concerns.

After Kouper was born Natalie repeatedly tried to raise the alarm that her son was not crying, moving or feeding. She was told this was normal and that only if he didn’t feed for 48 hours would they do anything. She said a lack of staff was obvious throughout her labour: “I didn’t see anybody for hours. I was constantly told they didn’t have enough staff.”

An independent investigation by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) found staff did not properly follow the trust’s reluctant feeder policy and had they done so Kouper would have had a detailed care plan and may have been referred to a neonatal unit which would have identified problems with his lungs and breathing.

An inquest concluded Kouper had died from a form of respiratory distress that affects premature babies but the cause for this was unknown. While the coroner said Kouper had been discharged appropriately, the inquest heard midwives had mistakenly assumed he had fed. HSIB said the notes from staff did not fit with the testimony of the family and it was impossible to know what really happened.

Natalie told The Independent her son cried once after birth, adding: “From then to the minute he died, he never opened his eyes, he never cried. He never moved, he didn't lift his arm, a finger, a murmur. He did nothing. If he hadn’t have cried looking back and as horrible as it is, I would have said he was stillborn.”

She said her concerns were dismissed by midwives and a junior doctor who examined Kouper and that discharge paperwork for her son was completely inaccurate.

“It was the exact opposite of what they did. At the bottom it stated he was happy and content. That the midwife had seen him feed, both breastfed and bottle fed and that he’d passed his hearing test, which he didn’t. If it didn’t have Kouper’s name on it I would have said it wasn’t his.”

The couple learnt at the inquest into their son’s death that a consultant at the hospital, who had not been involved in Kouper’s birth, had emailed the coroner trying to get Kouper’s cause of death listed as sepsis – despite no evidence of sepsis – though the coroner rejected this.

“They were deliberately trying to cover up. Sepsis for them would have been a win and for us it would have been game over,” said Dave.

Investigations into Kouper’s death found he may have had a metabolic problem and that it was not possible to know if he could have been saved by earlier interventions.

The trust has now reversed its feeding policy with active plans to be in put in place if a baby is reluctant to feed two hours after birth – compared with 48 hours previously.

“I know that fighting this and getting answers won’t bring him back,” said Natalie. But if just one baby survives from it, what happened to Kouper and what we’ve gone through as a family was worth it.

“We always think that we didn’t do enough. We should have made somebody listen to us. He is my son and I want answers.”

‘How many people have had the wool pulled over their eyes?’

The parents of Harriet Hawkins and Wynter Andrews have bonded over the tragedies that hit their families years apart. They believe that, had Nottingham Hospital made changes and learnt lessons after Harriet’s death in April 2016, then the loss of babies including Wynter in September 2019 could have been avoided.

Both families have faced what they believe to be attempted cover-ups and a lack of honesty from the NHS trust. It’s only through their determination that the truth has emerged.

For Jack Hawkins, the death of his daughter, who was stillborn, effectively ended his career as a consultant at Nottingham Hospital where he worked on the acute medical wards. Both he and Harriet’s mother Sarah, a physiotherapist at the trust, have been left “brutalised” by the process of fighting for three separate investigations into Harriet’s death and diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Harriet’s death was caused by delays in recognising Sarah was in active labour – this went on for six days as she was repeatedly told by midwives not to attend hospital. When she was eventually admitted, an ultrasound revealed Harriet had already died.

The trust did not declare Harriet’s death a serious incident for 159 days when this should be done within days. Its first attempt at an investigation contained multiple errors. Jack said: “Everything was wrong with it. They had us at the wrong hospital, the wrong mode of delivery. They said it was consultant-led care, and it wasn’t. They said it was induced, that Sarah had an infection but there were no signs of that. We insisted that they do a proper review.”

The trust then approached Joy Payne, then head of midwifery from Heartlands Hospital to carry out a review – afterwards, she was appointed head of midwifery at the Nottingham Trust.

Her draft report, sent to Jack and Sarah, said Harriet’s death was “directly contributed to” by five failings at the trust. But in the final version it said her death “might have been avoided” if the trust had acted differently. Jack said: “They had changed the sentiment at the end, the difference is a legal one, but a very important legal one.”

A final external review – commissioned by the local clinical commissioning group against the wishes of the trust – ultimately concluded Harriet’s death was “almost certainly preventable” and the trust has accepted liability.

For Wynter’s parents Sarah and Gary, who now live in Oxfordshire, there are many similarities to what happened to their daughter. Wynter was born by emergency caesarean section in September 2019 after significant delays. Sarah was given powerful doses of diamorphine, which can delay labour, without a doctor carrying out checks. Heart traces were misread and the ward was dangerously understaffed.

When Wynter was eventually delivered she had been deprived of oxygen for too long.

Sarah Andrews told The Independent: “If you look at what happened to Harriet, there’s quite a few similarities. Had the enacted the changes they promised, then what happened to Wynter would have been different. They had all that time in between Harriet’s death and Wynter’s death where they could have changed things and they didn't.”

After Wynter’s death Sarah was contacted by the Nottingham coroner’s office which had been told Wynter’s death was “expected” and had only been sent paperwork for the day of her birth and not the notes for the previous day while Sarah was on the ward and birth was delayed.

Sarah said: “I told the coroner I agreed with the cause of death but not how we got there. Had I not spoken up then, the coroner would have issued a death certificate and that would have been it.”

Again, the hospital did not declare Wynter’s death as a serious incident and breached rules on duty of candour – that requires hospitals to be honest after mistakes.

The trust has carried out reviews of serious incidents since the Hawkins’ case and acknowledged the deficiencies in her care.

It has also changed the way incidents are handled and assessed to ensure serious incidents are recognised and investigated properly and has appointed a family liaison officer to support bereaved families.

At an inquest into Wynter’s death last year the coroner heard that there was an unsafe culture on the wards at the trust, that midwives had not written their own statements but been coached by the trust’s legal department and that midwives feared raising concerns with consultants.

Sarah said: “How many of the families have slipped through the net that are out there whose babies have died that didn’t need to have died?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments