EU migrants won’t take advantage of the NHS because they don’t want it

There is a lot of pride surrounding the NHS and with it comes fear that EU migrants will take advantage of the universal healthcare system. But EU patients aren't that crazy about the NHS to begin with, say Chris Moreh, Derek McGhee and Athina Vlachantoni

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The National Health Service is often described as a “national treasure”. And it is a sentiment those on the left and the right of the political divide agree on. The public are so proud of the NHS that it was chosen as a central theme of the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympic Games.

But this pride has also been coupled with fears that the universal healthcare provided by the NHS might be taken advantage of by patients from outside the UK. A few months after the Olympics, the then-health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, felt the need to clarify that “we are a national health service, not an international health service”. The Conservatives’ election-winning manifesto of 2015 made this point even clearer when it pledged to “tackle health tourism” and “recover up to £500m from migrants who use the NHS”.

But our research shows that while the NHS may be a national treasure to British people, EU migrants would rather be treated in their countries of origin. As a 38-year-old woman from Germany put it: “Sorry, NHS? No thanks.” And the reasons for rejecting the NHS? A 25-year-old man from the Netherlands says it’s because the “NHS is slow and the medical care mediocre”. Or, at least, it “is rather poor compared with healthcare in my country”, according to a 45-year-old woman from Germany.

But why should British people worry about what EU migrants think of their health service? The answer is that these people are familiar with at least two European healthcare systems. They have the information and personal experience that most British citizens do not. There is a lot to be learnt from them.

Where would you rather be treated?

In an online survey of EU migrants in the UK, conducted as part of a broader research project, we asked respondents where they would rather have their medical treatment: in Britain, in their country of origin, or elsewhere? More than 1,600 respondents answered the question, and 513 explained the reasons for their choice.

Most of the respondents (78 per cent) came from three eastern European countries (Poland, Hungary and Romania), 14 per cent from three southern European countries (Portugal, Spain and Italy) and 8 per cent from three western European countries (Germany, France and the Netherlands).

Overall, only 36 per cent preferred medical treatment in the UK, while 46 per cent opted for their country of origin. The remaining 17 per cent were undecided and 1 per cent preferred a third country.

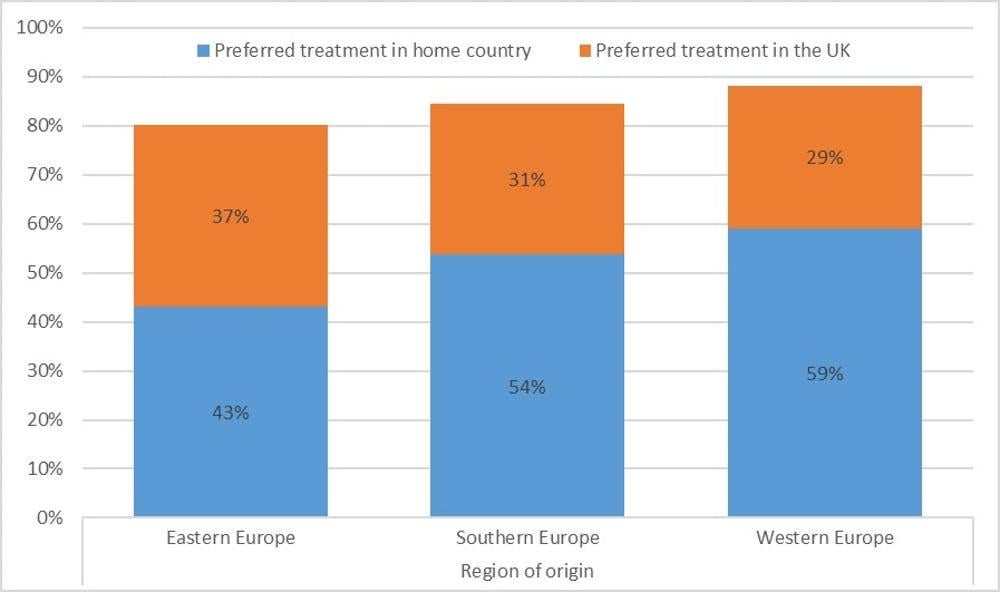

There were differences depending on the person’s region of origin. People from eastern Europe were more likely to choose treatment in the UK than those from southern Europe, who in turn were more likely to choose treatment in the UK compared with people from western Europe. This shows that migrants’ preferences are in line with the differences in the quality of healthcare in various European countries as measured by academically produced or consumer-oriented performance indicators, such as the Healthcare Quality and Access Index or the Euro Health Consumer Index.

These indicators rank healthcare in the eastern European countries in our study lower than British healthcare. Despite this, only 37 per cent of the eastern European migrants in our sample preferred to be treated in the UK.

A question of quality

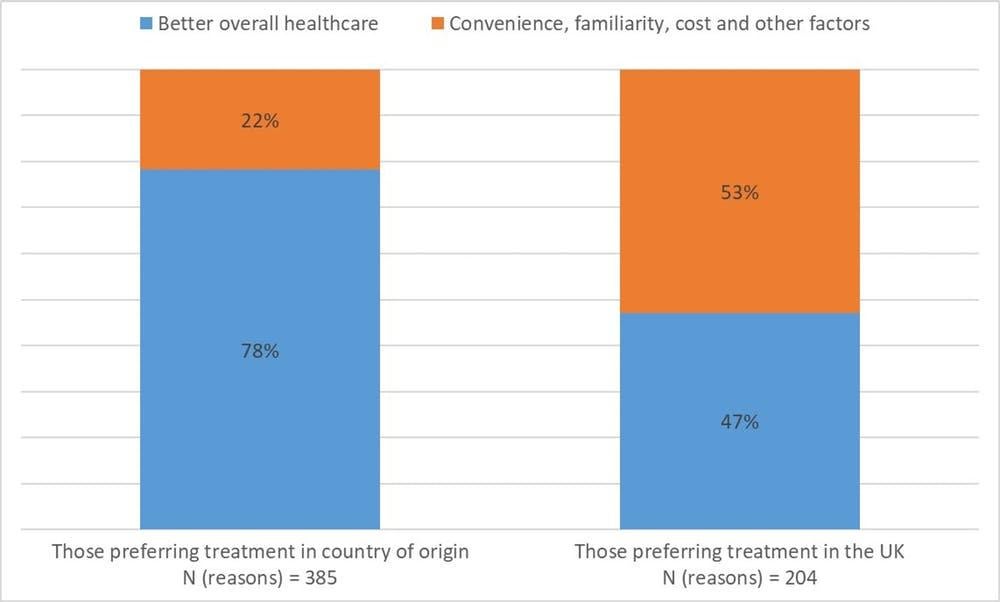

There may be many reasons for these preferences, but the respondents who explained their choice made it clear that it was mainly about the quality of healthcare. A total of 385 people explained their reasons for wanting treatment in their countries of origin, and 204 provided reasons for choosing the UK. These reasons broadly fell into the following categories: quality of healthcare; convenience; cost; and familiarity with the system.

Seventy-eight per cent of the reasons for preferring treatment in the countries of origin were based on a belief that healthcare was better there, while only 47 per cent of those who chose treatment in the UK thought British healthcare was better quality.

For most of those preferring the UK (53 per cent), the convenience of not having to travel or a sense of belonging in Britain were more decisive factors. As a 30-year-old woman from Poland put it: “I live here and so I trust this country’s health service.” The general sentiment, however, is closer to that expressed by another 29-year-old Polish woman who doesn’t trust the NHS. “It’s good to live in the UK,” she says, “but best not to get ill here.”

British people might be inclined to dismiss these opinions out of pride. But if British patients want the best for themselves, they should ask policymakers to have an objective look at what works best elsewhere and adopt it in the UK. If they don’t, the NHS might eventually lose its status as a “national treasure”. And that truly would be a tragedy of Olympic proportions.

Chris Moreh is a lecturer in sociology at York St John University. Athina Vlachantoni is a professor of gerontology and social policy at the University of Southampton. Derek McGhee is a professor of sociology at Keele University. This article originally appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments