Interstitium: New organ discovered in human body after it was previously missed by scientists

'Interstitium' acts as a shock absorber for vital tissues and could improve understanding of cancer spread

Scientists have identified a new human organ hiding in plain sight, in a discovery they hope could help them understand the spread of cancer within the body.

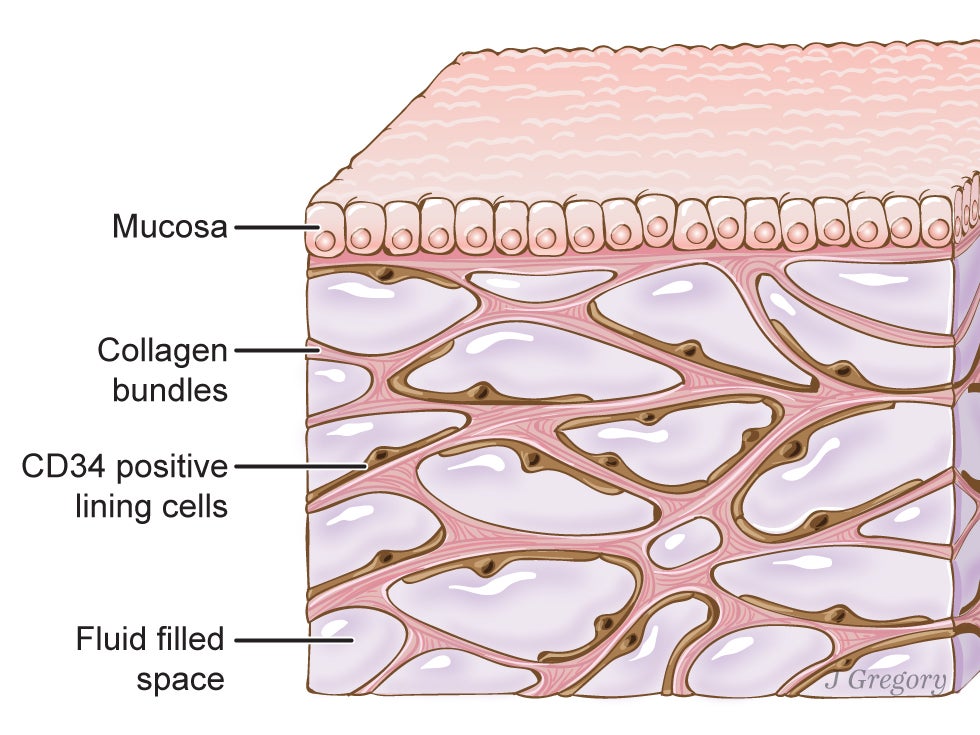

Layers long thought to be dense, connective tissue are actually a series of fluid-filled compartments researchers have termed the “interstitium”.

These compartments are found beneath the skin, as well as lining the gut, lungs, blood vessels and muscles, and join together to form a network supported by a mesh of strong, flexible proteins.

New analysis published in the journal Scientific Reports is the first to identify these spaces collectively as a new organ and try to understand their function.

Remarkably, the interstitium had previously gone unnoticed despite being one of the largest organs in the human body.

The team behind the discovery suggest the compartments may act as “shock absorbers” that protect body tissues from damage.

Mount Sinai Beth Israel Medical Center medics Dr David Carr-Locke and Dr Petros Benias came across the interstitium while investigating a patient’s bile duct, searching for signs of cancer.

They noticed cavities that did not match any previously known human anatomy, and approached New York University pathologist Dr Neil Theise to ask for his expertise.

The researchers realised traditional methods for examining body tissues had missed the interstitium because the “fixing” method for assembling medical microscope slides involves draining away fluid – therefore destroying the organ’s structure.

Instead of their true identity as bodywide, fluid-filled shock absorbers, the squashed cells had been overlooked and considered a simple layer of connective tissue.

Having arrived at this conclusion, the scientists realised this structure was found not only in the bile duct, but surrounding many crucial internal organs.

“This fixation artefact of collapse has made a fluid-filled tissue type throughout the body appear solid in biopsy slides for decades, and our results correct for this to expand the anatomy of most tissues,” said Dr Theise.

Freezing biopsy tissue taken from the bile ducts of 12 more patients enabled the team to preserve the anatomy of their newly discovered structure.

They realised the layer drains into the lymphatic system – the network of vessels transporting lymph, which is involved in the body’s immune response.

Besides their ability to cushion the body’s organs and protect them from harm, the researchers found evidence that cancer cells from tumours could make their way via the interstitium into the lymphatic system.

In providing a highway for fluid to move around the body, the interconnected cells of the interstitium may therefore have the unfortunate side effect of spreading cancer around the body.

Understanding this newly discovered frontier in human anatomy could allow scientists to develop new tests for cancer.

“This finding has potential to drive dramatic advances in medicine, including the possibility that the direct sampling of interstitial fluid may become a powerful diagnostic tool,” said Dr Theise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks