Marburg virus outbreak: What you need to know as Europe fears cases

Virus, which has similarities to Ebola, has killed at least twelve people during an outbreak in Rwanda

An outbreak of a highly infectious disease has killed at least twelve people in Rwanda, sparking concerns of a wider spread.

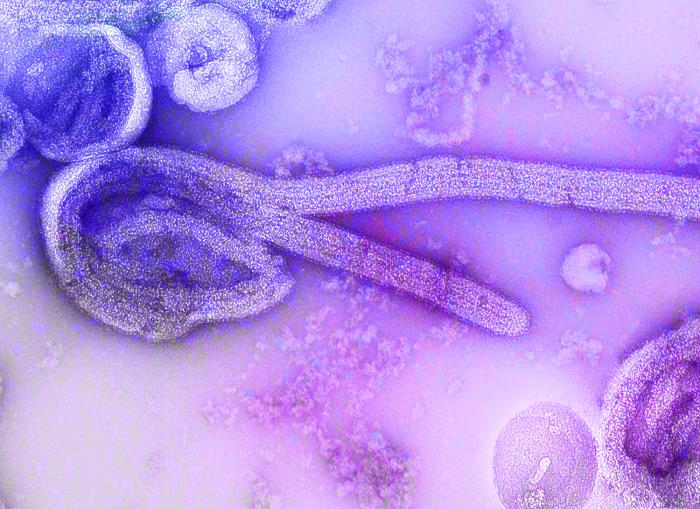

The Marburg virus disease, which is similar to Ebola, has killed hundreds of people in recent years, mostly in African nations. It is fatal for about half the people it infects according to data from the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The latest outbreak was detected in September 2024, marking the first time cases have been found in Rwanda. There are now 46 confirmed cases alongside the nine deaths. Around 300 people are also being monitored, having been in close contact with infected patients.

There were fears that the disease had spread to Germany as passengers were evacuated from a train after man with recent travel history to Rwanda developed flu-like symptoms. The two people feared to be infected were evacuated from the train by crew with full protective gear, but later tested as negative.

One of the 300 being monitored also travelled from Rwanda to Belgium but is not thought to be a risk to public health after completing the 21-day monitoring period.

Most of the victims of the current outbreak were healthcare workers in a hospital intensive care unit, Rwanda’s health minister has confirmed. In a statement at the end of September, the ministry said it was “closely monitoring the situation” with investigations underway to determine the “origin of the infection.”

An update from WHO has confirmed that seven of Rwanda’s 30 districts have reported cases. Of these, over 70 per cent are healthcare workers from two health facilities in the capital, Kigali.

Several of these districts are located on Rwanda’s border, the organisation says, increasing the risk of spread to East African nations: the DRC – which is already dealing with an outbreak of Mpox – Tanzania and Uganda.

Responding to the reports, the WHO’s director-general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “WHO is scaling up its support and will work with the government of Rwanda to stop the spread of the virus and protect people at risk.”

Rwandan authorities have now begun vaccine trials for the fatal virus. The country has received 700 doses from the Sabin Vaccine Institute, a US-based non-profit organisation, to help with the effort.

WHO has said the risk of the outbreak is “very high at the national level, high at the regional level, and low at the global level.”

What are the symptoms of Marburg virus disease?

Marburg virus disease is highly contagious and can cause haemorrhagic fever with a fatality ratio of up to 88 per cent. There is currently no vaccine or specific treatment.

The time between infection and the onset of symptoms can vary and is usually between two and 21 days. These will be felt “abruptly” says WHO, beginning with high fever, severe headache and muscle pains.

More symptoms usually show after another three days, commonly including:

- watery diarrhoea

- stomach pain

- nausea

- vomiting

WHO writes that at this phase “the appearance of patients at this phase has been described as showing ‘ghost-like’ drawn features, deep-set eyes, expressionless faces, and extreme lethargy.”

Between five and seven days, forms of bleeding will usually begin and, in fatal cases, it will be severe blood loss that causes death. This will be in the form of blood in the vomit, faeces and several orifices.

The disease was initially recognised in 1967 following two large simultaneous outbreaks in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany, and in Belgrade, Serbia. It is thought that the disease initially results from prolonged human exposure to caves or mines inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks