Hospital superbugs could be tackled with chemical glue that allows antibiotics to be combined, study suggests

Technique could speed up drug discovery and also applied to cancer treatments to help boost existing treatments

A simple method for fusing antibiotics and other drug molecules into a single compound could offer new hope in the fight against globally rising levels of drug resistance, a study suggests.

The novel technique allows to chemicals to be paired simply by mixing them with an amino acid called selenocysteine. It was developed by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Tests with the key antibiotic vancomycin found that pairing it with another antimicrobial element made the drug up to five times more potent, according to their paper published in the journal Nature Chemistry.

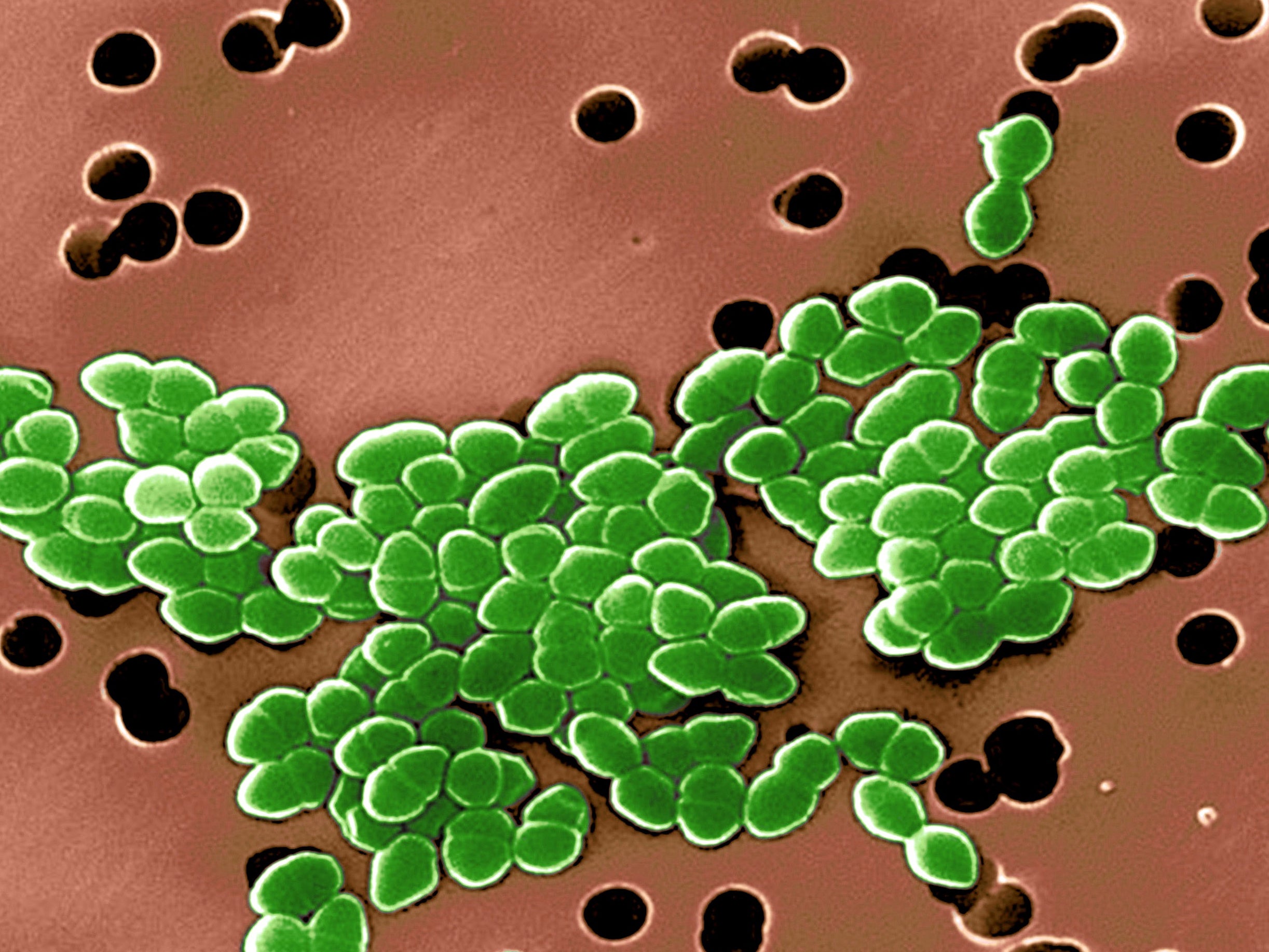

This allowed it to treat strains of bacteria which commonly cause infections in hospitals and which would usually be unaffected by vancomycin, meaning a more powerful drug would be needed.

The findings comes as health experts warn that the failure to tackle antibiotic resistance could push medicine back to the dark ages, when simple infections and minor surgery became life threatening.

These new chemicals have not yet been tested in animals and it is possible that the pairing of two safe drugs might lead to more toxic side-effects for humans, as well as the bacteria they’re meant to treat.

However the authors said it could help rapidly speed up new drug development at a time when bacteria are evolving resistance to even our antibiotics of last resort more quickly than new drugs are being found to replace them.

“Typically, a lot of steps would be needed to get vancomycin in a form that would allow you to attach it to something else, but we don’t have to do anything to the drug,” says Dr Brad Pentelute, an MIT associate professor of chemistry and the study’s senior author. “We just mix them together and we get a conjugation reaction.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use is a major driver of resistance, with drugs often given for viral infections – like the flu – where they will have no effect.

They are also widely used in farming to promote the growth of animals. This creates a massive testing ground for bacteria to develop strategies that let them withstand or neutralise the drugs.

The process takes advantage of one of the properties of selenocysteine, which occurs naturally in the body, to latch on to more complex molecules which have a ring of carbon atoms as part of the molecular structure.

Seleoncysteine attaches in the same place every time and this means it has potential for industrial scale drug production as it means the new compounds it creates are identical each time.

The method could also work for other molecules with similar structure and could potentially be used in cancer treatment to attach chemotherapy drugs to other molecules which will help it get into tumours and kills them.

“That’s the beauty of this method,” said Dr Chi Zhang who also worked on the project. “These complex molecules intrinsically possess regions that can be harnessed to conjugate to our protein, if the protein possesses the selenocysteine handle that we developed. It can greatly simplify the process.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks