Women also use drugs – not that you can tell from drug policy

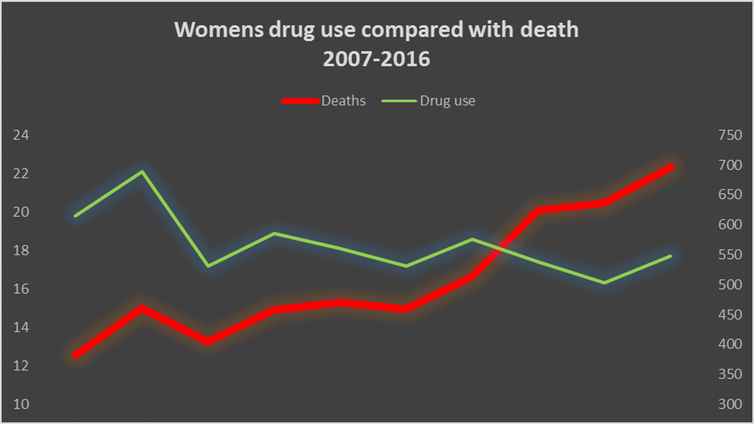

Drug-related deaths have risen for men and women over the past decade, but the sharpest rise has been for women – so why is UK drug policy ignoring them?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the UK, men are more likely to try drugs than women, and they significantly outnumber women in accessing treatment, reinforcing the view that male drug use is the norm. But there are limitations with the way drug use is calculated and serious issues with women accessing treatment.

Drug policy and the allocation of budgets for drug prevention and treatment are informed by surveys such as the Crime Survey for England and Wales.

The survey shows that twice as many men as women use drugs. However, the survey misses some key groups, such as homeless people and university students.

The latter is particularly important as there are more young women in university than men. Another important group not included in the survey is prisoners.

Female offenders are more likely than their male counterparts to use drugs and to report needing help when they enter prison. As a result of these issues, the number of women who use drugs is probably massively underestimated.

Vulnerable group

Estimates of female drug use matter as we know that women use drugs not just for pleasure but to cope with difficult life circumstances, such as domestic abuse. There are clear links between experiencing abuse and trauma and having problems with drugs and alcohol.

The connection between these issues is explored by the authors on BBC Radio 4’s Women’s Hour. Women are thought to progress more rapidly from starting to use drugs to the point where they develop problems, such as dependency – a phenomenon known as “telescoping”.

Given this phenomenon, it is concerning that 11 to 15-year-old girls are more likely to drink alcohol or try cigarettes than young boys. Girls also match boys of the same age in their use of drugs.

This rapid journey into a problematic relationship with drugs could be a contributing factor to the significant rise in drug-related deaths among females.

Drug-related deaths have risen for men and women over the last decade, but the sharpest rise has been for women. And this rise could be underestimated as coroners are less likely to investigate unnatural deaths in women, compared with men.

The data on drug-related deaths shows that 31 per cent of female deaths were “intentional”, compared with 17 per cent of male deaths, but there has been very little analysis or exploration into why this phenomenon is occurring.

Barriers to treatment

The United Nations has recently drawn attention to the barriers faced by women who need treatment for drug dependency. Men outnumber women in treatment by more than three to one, and some of these men will be perpetrators of violence towards women.

Entering these male-dominated treatment centres can be hazardous for women. They might be abused by men they are in a relationship with, or by men who have experience of exploiting women. Unlike men, many women will be introduced to drugs by a partner rather than a friend.

Unfortunately, for some women, this means the man can take control of their drug use. Then there are the conflicting images of motherhood and of drug use, particularly problem drug use where women fear – often rightly – that their children will be taken into care if they disclose their habit to the authorities.

Often women in treatment who have children will be subject to a higher level of scrutiny and more onerous treatment practices, such as daily pick-up of their medication, such as methadone, simply because they have children. Women of colour face particular bias both in the treatment system and in prison.

The recent report from David Lammy MP provided an analysis of the racial disparity that exists in the criminal justice system. Black women are 2.3 times more likely than white women to be jailed for the same drug offence.

Bias in academia

Women are underrepresented in studies about drug use and even when they are included their outcomes are often not reported. This is not helped by a lack of women in senior research positions. Worse, male researchers are in denial about this gender bias.

Finding ways of preventing harm from drugs, and effective treatments for those who do develop problems, requires the best scientists, regardless of their gender.

Nowhere is the lack of consideration of women’s specific experiences with drugs more apparent than in the UK’s Drug Strategy 2017.

The strategy only mentions women three times: as victims of domestic violence, as sex workers and in relation to drug-related deaths.

It in no way tries to tackle the unique harms women face or the significant barriers to treatment, despite the fact this may be one of the drivers for the tragic rise in women dying.

Ian Hamilton is a lecturer in mental health and addiction at the University of York. Niamh Eastwood is a visiting lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University. This article originally appeared in The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments