How effective were Covid lockdowns – and should we use them if another pandemic hits?

While the Covid inquiry focuses on Boris Johnson, there remain fundamental questions about the use of lockdowns – and whether such blunt tools are the right way to control infections, writes epidemiologist Adam Kucharski

Boris Johnson has finally taken the stand at the Covid inquiry, an opportunity to defend himself against a barrage of criticism from politicians, advisers and civil servants who served with him as the pandemic engulfed the UK.

The use of lockdowns and their impact on the death toll remain fundamental questions: how effective were they in reducing the spread of the disease and if – or when – a similar pandemic hits us, what role should they play?

As a professor of infectious disease epidemiology, I spent the pandemic analysing the data on these questions.

The first signal that the spring 2020 Covid wave was going to decline in the UK didn’t come from case numbers or hospitalisations. It came from data on social interactions. On 24 March, one day after the population was told to “stay at home”, my colleagues ran a behavioural survey. They found that social contact among UK adults had dropped 75 per cent compared to pre-pandemic levels, enough to tip the growing epidemic into decline.

The extent of behavioural change in 2020 was unprecedented. Although social distancing measures were introduced in the US during the 1918 influenza pandemic, they reduced transmission by at most 30-50 per cent. The epidemic waves therefore declined only after a large proportion of the population had been infected, and hence developed immunity.

Cases of Covid in the UK would eventually fall, but the questions would grow. What effect had lockdown restrictions had on the epidemic? Was it necessary to stay at home? How much could measures be lifted without causing a second wave?

To estimate the impact of Covid lockdowns, we must first agree on the basics of respiratory virus transmission. Some have claimed – against the available evidence – that the first UK wave declined because a large proportion of the population somehow got infected in early 2020 and developed strong-but-invisible immunity. Fortunately, most agree with the reality that there was a huge reduction in social contact in the UK during March 2020. And because Covid spreads through such interactions, the first wave declined with only a small proportion of the UK population (i.e. 5–10 per cent) infected.

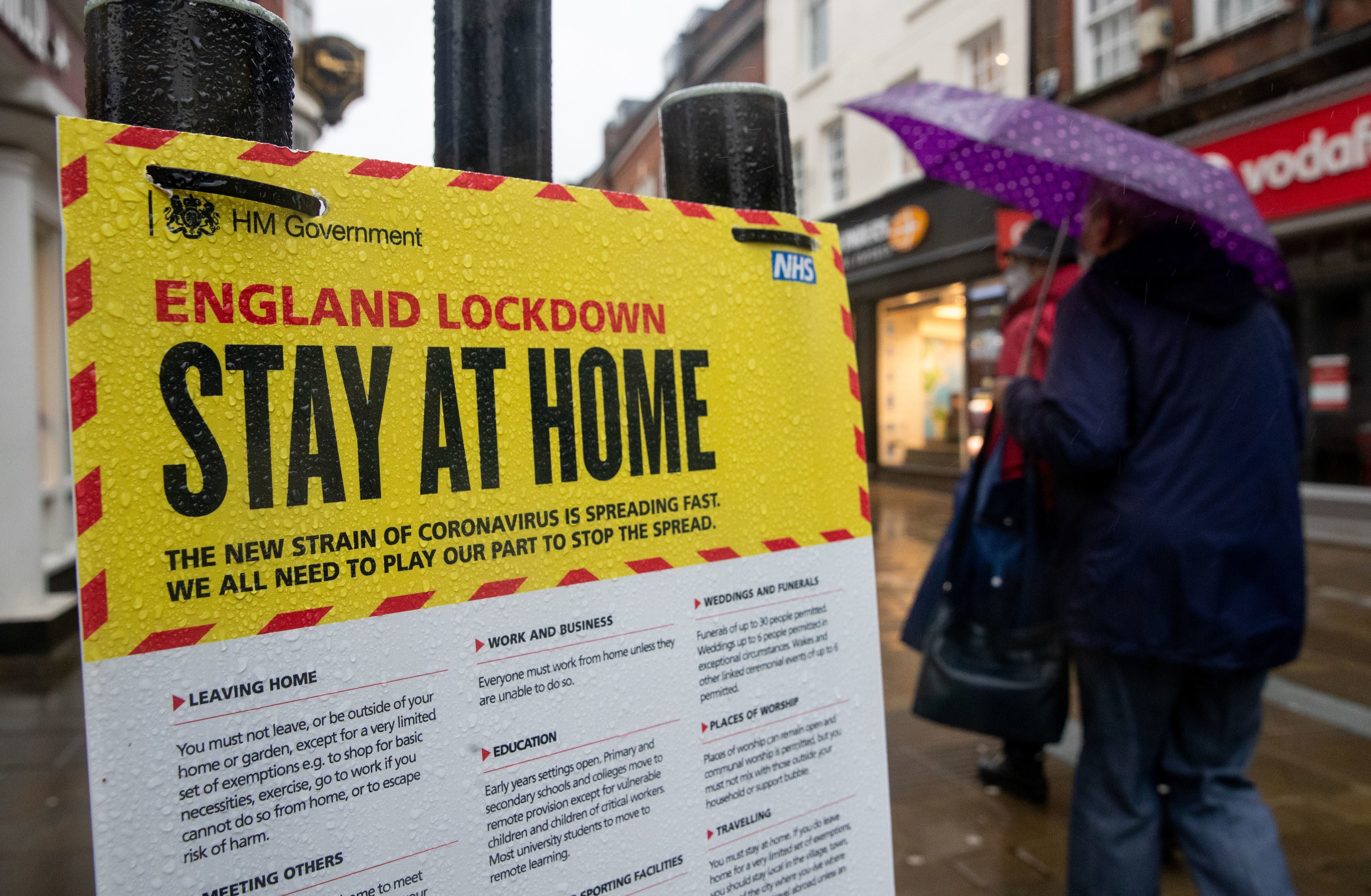

To analyse the effect of lockdowns, we must next agree on what counts as a lockdown. On 17 March 2020, the day after the UK government advised people to avoid non-essential interactions, The Times carried the headline “Britain in lockdown”. Meanwhile, others were using lockdown as a synonym for cordon sanitaire ie “locking down travel” in and out of an area. One widely shared 2021 report even defined lockdown to mean any government measure. However, public discussions in the UK have generally come to define a lockdown as a stay-at-home order.

In March 2020, the UK introduced numerous measures in a short space of time. After the guidance to avoid non-essential contacts on 16 March, schools, pubs, clubs, gyms and restaurants were ordered to close on 20 March. Then came the 23 March lockdown.

If we want to understand the relationship between control measures and transmission, we need to know what the underlying epidemic looked like. Unfortunately, UK testing was very patchy early in the pandemic. As a result, the most solid data are metrics like deaths and rises in antibody levels, both of which can occur weeks after infection.

In 2020, statistician Simon Wood used data on deaths in the UK, as well as delays from infection to death, to estimate when the original infections occurred. His analysis suggested UK infections peaked around 19-21 March, the same time that many venues closed.

At the peak of an epidemic, there is no growth but also no decline. If the UK epidemic had remained flat after the sharp peak Wood estimated, the outcome would have been around 2,000 fatal infections per day. The reason we didn’t see 2,000 deaths a day in the first wave is that infection levels soon fell; Wood’s results suggest the fastest rate of decline was around 24-26 March, just after the lockdown.

This timeline is broadly consistent with behavioural data. In a survey by YouGov and Imperial College London on 17-18 March, just over half of UK adults said they were avoiding crowded areas and social events. The biggest changes came in the second half of the month. Mobility data from Google suggests visits to workplaces were down 15 per cent on pre-pandemic levels by 20 March 2020; by the end of the month, they had fallen 65 per cent. In a YouGov survey on 24 March, 93 per cent said they supported the new stricter lockdown measures.

The UK often introduced or relaxed multiple measures at once, so it’s unlikely we’ll ever know the impact of each one definitively. Randomised trials of control measures were rarely conducted, and background behaviour can change for a variety of reasons. For example, schools and many workplaces routinely close during the Christmas period, which meant most people in the UK on average had slightly fewer contacts during the December 2020 “non-lockdown” period than the spring 2020 lockdown.

Countries will need to find a better alternative for future severe pandemics

Given the uncertainty about UK-specific measures, another option is to bring together data from multiple countries. Researchers at the University of Oxford have compared the timing of measures across Europe during the spring and autumn Covid waves to estimate whether certain measures were on average linked with larger effects. They estimated that no single measure led to a more than 50 per cent reduction in transmission; it required a combination to curb the epidemic. Strict limits on gathering size reduced transmission by 25-40 per cent, while closing businesses led to a 25-35 per cent reduction. Moreover, they estimated that once venues had been closed and gatherings restricted, stay-at-home orders led to an additional 10-15 per cent reduction, albeit with a lot of uncertainty on that number.

Context matters here. If a country is facing 2,000 deaths a day, a 10 per cent transmission reduction that tips the epidemic into decline will have much more impact than a 10 per cent reduction when an outbreak is already well under control. But defining the value of this impact – and the acceptability of the costs it incurs – is not just an epidemiological question. It depends on the objectives a country has and the wider economic, social, and health effects that must be weighed up.

Comparing countries is also more than just an epidemiological question. On paper, Peru had some of the most stringent Covid measures in the world in 2020. But they also ended up with a large percentage of people infected and high death rates, because the social and economic factors around lockdowns were not the same as in Europe. Then we have Sweden, which saw a drop in transmission despite fewer reductions in social interactions. But Sweden also has better sick pay and smaller household sizes compared to the UK. So more people could afford to isolate and would infect fewer others when they did so.

It’s important to understand what happened during Covid, but it’s also crucial to look to the future. In Europe, lockdowns were a blunt, last-ditch tool. They were implemented reactively in response to rapidly rising cases in spring 2020, without a clear exit strategy.

Countries will need to find a better alternative for future severe pandemics. Should – and could – the UK make more use of digital footprints to identify at-risk contacts and stop chains of transmission, like South Korea or Singapore did for Covid? Should it try to eliminate transmission domestically, then rely on border measures to prevent new outbreaks, like Vietnam and New Zealand did? Or should it do something else entirely?

When the next pandemic hits, it is not enough to ask simply whether we should lock down. The evidence shows that cutting social contacts at the right time will curb the spread of disease. But having lived through this once, we should be in a better position to ask what we are hoping to achieve – and what trade-offs we are willing to accept to get there.

Adam Kucharski is a professor of infectious disease epidemiology and the co-director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s Centre for Epidemic Preparedness and Response

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments