The death of a friend can be as traumatic as losing a family member

Losing a close friend can take a heavy toll on a person’s health and wellbeing, Liz Forbat and Wai-Man Liu have discovered. So why is that grief not taken seriously by employers or doctors?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The death of a friend is a loss that most people face at some point in their lives – often many times. But it is a grief that may not be taken seriously by employers, doctors or others. The so-called hierarchy of grief, a scale used to determine who is considered a more legitimate mourner than others, puts family members at the top. For this reason, the death of a close friend can feel shunted to the periphery and has been described as a disenfranchised grief.

There has not been much research on the impact the death of a friend has on a person, so we set out to address this with our latest study. We discovered that, far from being a trivial loss, the health and wellbeing of people who lose a close friend suffer a heavy toll in the four years after that loss.

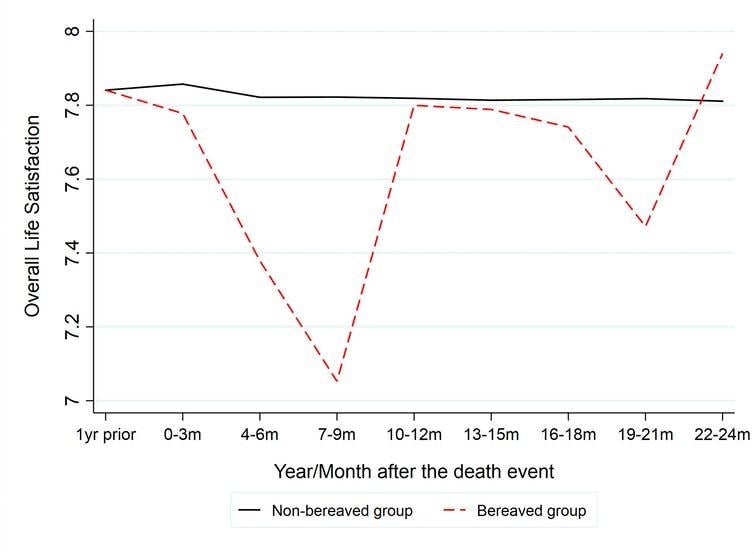

For our study, published in PLOS One, we analysed responses from an Australian household survey of more than 26,000 people. Of the people who completed the survey, over 9,500 had experienced the death of a close friend. Our analysis showed that life satisfaction of the bereaved fell sharply (see below) compared with a matched non-bereaved group. There is a large and sharp drop in this life satisfaction from month three to nine and another smaller yet still sizeable drop at months 19 to 21.

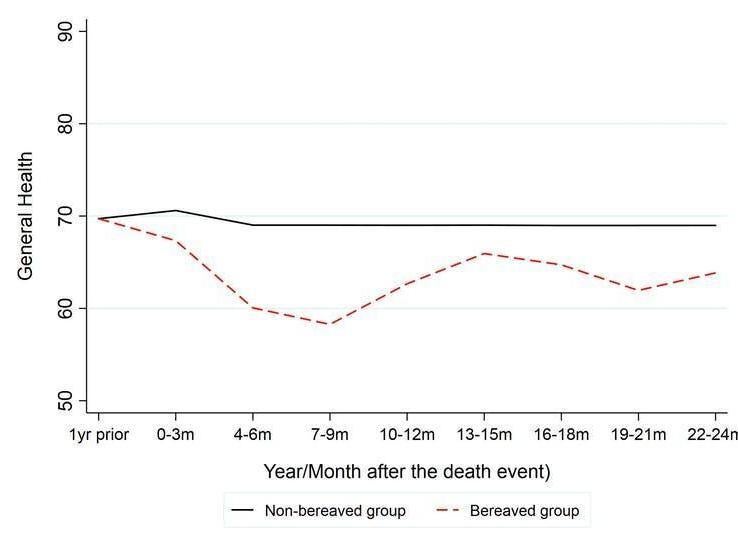

In the graph below, the impact on general health is shown comparing the bereaved group with a matched non-bereaved group. You can see the bereaved group tracking clearly lower than the non-bereaved for 24 months, an effect that continues for four years.

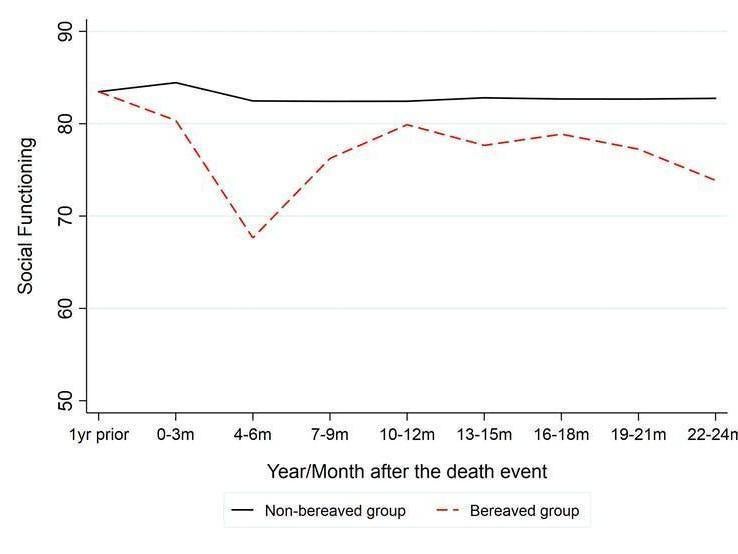

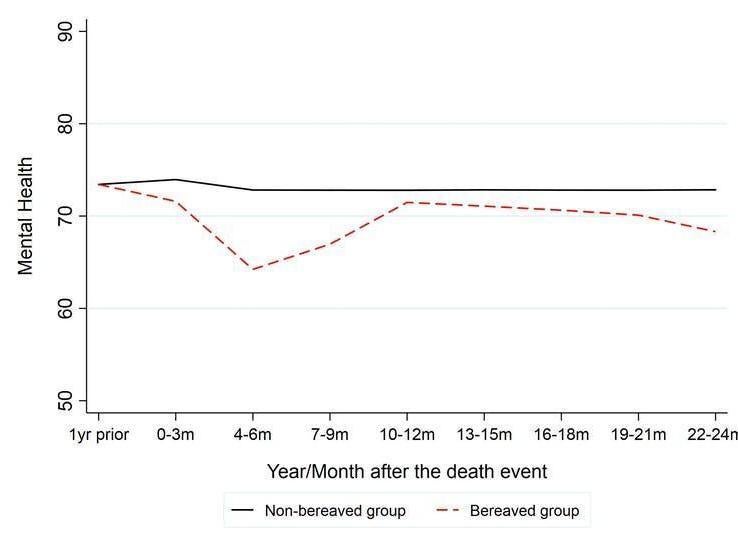

Social functioning and mental health are also worse after the death of a friend, which you can see in the final two graphs.

These findings suggest we need to take the death of a close friend more seriously and to change the way we support people who are suffering from such a bereavement.

Friends are psychological kin, that is, you may even have a stronger bond with friends than people you are related to by birth or marriage. So when a friend dies, the psychological and emotional stress can be as bad as the death of kin.

Our analysis shows that if you’re not socially active, the death of a friend can make the impact of the bereavement worse. As your social circle shrinks, you become less resilient to grief because you lose a key source of emotional support from your social network.

The folklore that feelings of sadness and loss reduce considerably after a year also needs to be challenged. Although there are improvements in health and getting on with everyday life, the longer-term effects on mental health and wellbeing cannot be ignored. This is especially worrying for disenfranchised grief – not only are there marked and enduring long-term effects, but there’s also little recognition that the bereavement was significant.

Mental health professionals and employers should now acknowledge the significant effect the death of a friend can have on a person, and offer appropriate services and support. The psychological help bereaved people receive is not the same across the board, and this needs to change as we begin to accept the idea that close friends can be considered as psychological kin.

Liz Forbat is an associate professor of ageing at the University of Stirling. Wai-Man Liu is an associate professor at the Research School of Finance, Actuarial Studies and Statistics, Australian National University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments