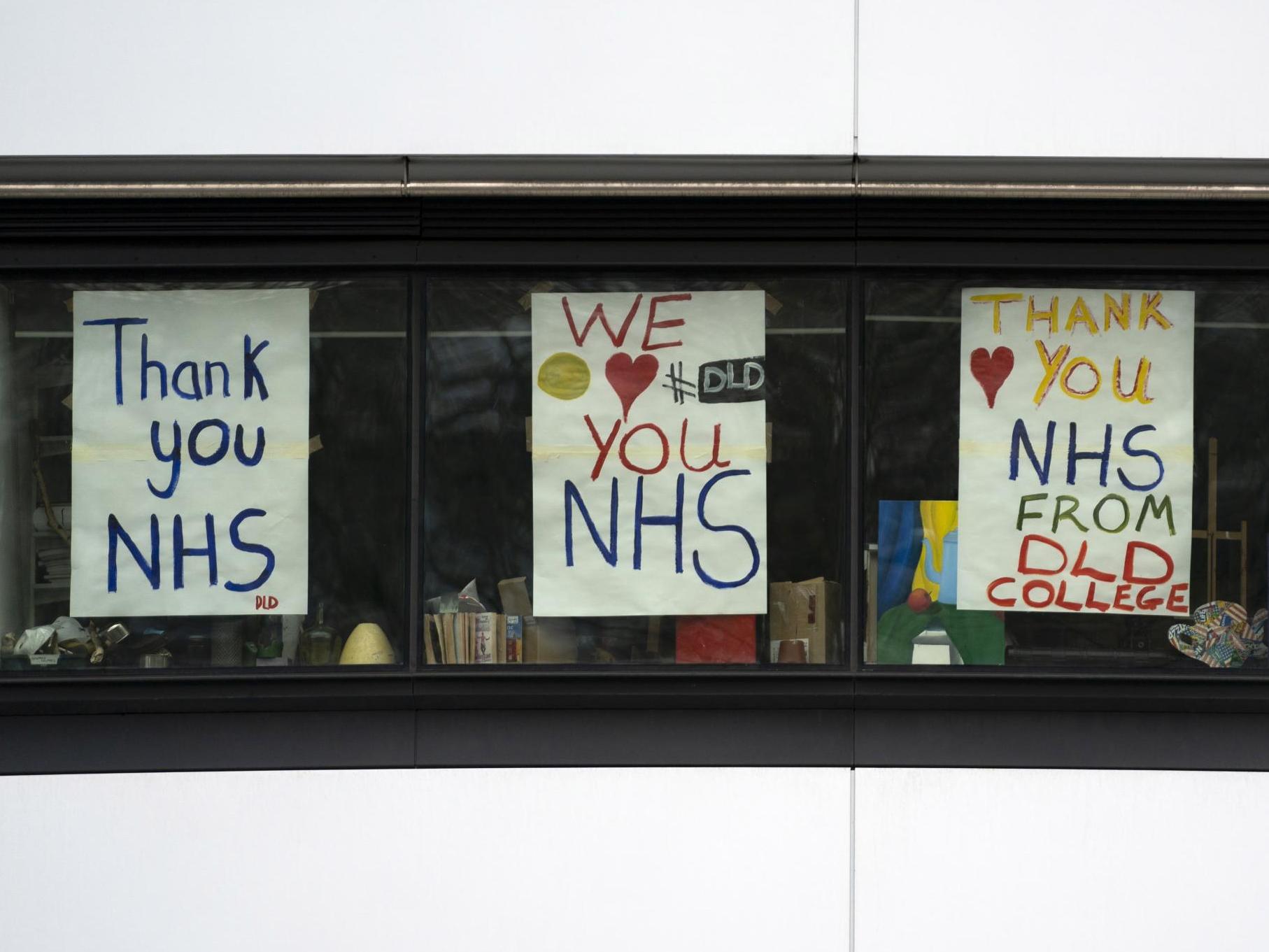

Coronavirus: Returning NHS workers explain why they are joining the battle against the pandemic

‘When you become a nurse, it’s in your blood. You can’t turn away,’ one returnee tells Jon Sharman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Retired NHS staff and others whose work has taken them off the front lines are returning in their thousands to help the fight against coronavirus.

They have been praised for proving that “there is such a thing as society” after 20,000 answered a call to help.

Their expertise will be put to use not only on wards but in support services and broader organisational planning.

Professor Maureen Baker, a former chair of the Royal College of GPs (RCGP) where she coordinated the response to H1N1 swine flu, told The Independent she hoped to employ what she learned in that outbreak.

She said: “I’m part of a small group in RCGP that’s working through how best the college can support its members and the profession. I’ve also got my temporary licence to practise from the GMC [General Medical Council]. I’m in discussions with NHS England on contributing to their NHS 111 service.”

Professor Baker intends to work for the non-emergency number 111, advising callers whether or not they should go to hospital.

She added: “I was kind of assuming that the call would come. I thought, yes, this is something I can do. Having spent such a lot of my working life thinking about and preparing for pandemic risk, it seemed only right and proper to make a contribution.

“Even if I hadn’t been involved, I think at this moment when people are going the extra mile, it would seem the right thing to do. I’m encouraged by [the scale of the response]. It’s a vocation at the end of the day even when you’re retired. You still want to do something to help.”

And not every returning medic needs to be deployed at the sharp end of things, she said. “Taking up some of the slack to free up time for people who are currently in the workforce is part of what can be done. I think everybody’s got something to give. If I was 10 or 15 years younger I would have a lot more energy, that’s for sure.

“I’ve spent the best part of 40 years being able to talk to patients, listening to them and making a judgement. That’s still something I can do.”

Professor Baker cautioned that the new system would inevitably take time to hit its stride because it had been “set up very quickly from a standing start”, adding: “I think we need to be a bit understanding if it takes a while before we’re contacted or ... for various things to go through.” She said she would use her experience to suggest ways the scheme can be improved.

James Smith, whose day job is in the humanitarian sector, plans to take at least one shift a week as a locum A&E doctor in northeast London.

“There’s a fairly universal feeling among people who work for the NHS that, despite our frustrations with an understaffed and under-resourced health system, that we’re collectively and fundamentally proud to be working in a healthcare system that’s available and accessible for almost everybody free of charge at the point of care,” he told The Independent.

“I had drifted away from direct clinical practice to work in the humanitarian sector, but always felt that close affinity. It’s part of the reason why I’ve maintained my clinical licence to practice. There’s also that moral obligation that you feel, when you’re hearing the news and you’re hearing from your colleagues who are still working about the challenging conditions.”

That solidarity extends around the world, he said, as evidenced by Cuban doctors travelling to Italy.

But Dr Smith said he had some concerns about bringing back people whose knowledge of the latest medical research is lacking, and that filtering some of them into support roles – freeing up medics who are currently practising – made sense. “From an ethical and effectiveness point of view, it’s probably the more sensible course of action.”

He added that supporting the returnees both physically with personal protective equipment (PPE), and mentally, was vital.

Ministers have come in for sustained criticism for failing to get PPE to the front lines quickly enough or in great enough quantities. Some doctors have even bought their own and improvised by using ski masks, an MP said this week.

Testing of health workers has also lagged far behind what the government is aiming for.

Dr Smith said: “The government is tapping into what they know is a deep-seated desire among health professionals to care for each other and for the wider community. In taking advantage of that desire and moral obligation … there also has to be reciprocity from the state.

“We’re giving to the health system, and the state needs to make sure that it puts in place the necessary protections. If you want healthcare workers to be on the front line, you have a duty of care to those people.”

A lack of resources – of staff, ventilators and oxygen – is also now forcing medics to make terrible choices which “can be very distressing and psychologically damaging”, Dr Smith added.

Experience of such decisions, likely to be in greater demand than anyone wants to think about, will be brought by returnees like Dr Laura Green.

Dr Green, a nursing lecturer at the University of Manchester, told The Independent she would work one 12-hour shift a week while keeping up her class schedule. Some of her third-year students are already out in practice.

The former Macmillan nurse specialises in palliative care, and believes that there will be “a lot of people for whom [coronavirus treatment] is going to be end-of-life care”, even though most cases will be treatable.

She added: “One of the things I used to do a lot in practice was have difficult conversations with families. All those conversations about end-of-life care, they’re going to have to be had in a very sped-up way.

“Families aren’t able to be with their loved ones when they’re dying.

“The problem is, usually in palliative care we have weeks and months to have these conversations with people. With Covid-19 there’s no time.”

By the time that a minority of very ill patients arrive at hospital in the current pandemic, medics are faced with the appalling question of whether they are likely to be able to save them, and if not, whether they should reserve capacity for other victims.

Hospitals have been given national guidance on how to make those choices. But people like Dr Green will then have to find new ways to connect families with isolated patients and lead the conversation about how to care for the dying, such as using smartphones – a prospect she finds “daunting”.

Her experience of treating people with advanced cancers will not always help when treating coronavirus patients.

“It’s really horrible. I think it’s kind of how it is, and people really need to know that this is how it is,” she told The Independent. Seriously ill patients must confront their own dilemma: stay out of hospital and be surrounded by family, or die alone surrounded by medics garbed in protective plastic outfits.

“It’s unprecedented – it’s a really scary time to be a nurse, or anyone, really,” Dr Green said. Despite that, she said she feels compelled to help.

“I’ve decided to do these shifts because the Nursing and Midwifery Council code of conduct tells all nurses that while registered they must put the needs of patients above all else,” she added.

“The NHS is something I’ve been proud of for my whole life, even more so when I qualified as a registered general nurse in 2004. I’m frightened of getting ill. I’m frightened of not seeing my family. But when you become a nurse, it’s in your blood. You can’t turn away at a time like this.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments