Vaccine targeting common gut bacteria E.coli could help prevent cancer, scientists suggest

Proboitics and vaccines for two E.coli strains could hold the key to reducing bladder and colon cancer, researchers suggest

Vaccines targeting common gut bacteria E.coli could reduce rates of colon cancer in countries such as the UK, scientists have suggested.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute have suggested higher rates of colorectal, bladder and prostate cancers across industrialised countries could in part be explained by two strains of E.coli which cause high rates of urinary tract infections and bloodstream infections.

In a paper, published in The Lancet, scientists suggest a vaccine or probiotic which prevents these two strains from circulating could reduce the risk of cancer. However, they stress further investigation would be needed.

Professor Jukka Corander, senior author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, University of Oslo and the University of Helsinki, said: “We have been using large-scale genomics to track E. coli strains across multiple countries for the last 5 years, using data that goes back to the early 2000s.

“This has allowed us to start to see the possible connections between two E.coli strains and cancer incidence rates.”

She added, “by working together with cancer and microbiome experts, we are hopeful that in the future this work might lead to new ways to eradicate colibactin-producing E. coli strains.

“Vaccines or other interventions that target these E.coli strains could offer huge public health benefits. Such as reducing the burden of infections and lessening the need for antibiotics to treat these, as well as reducing the risk of cancers that could be linked to the effects of colibactin exposure.”

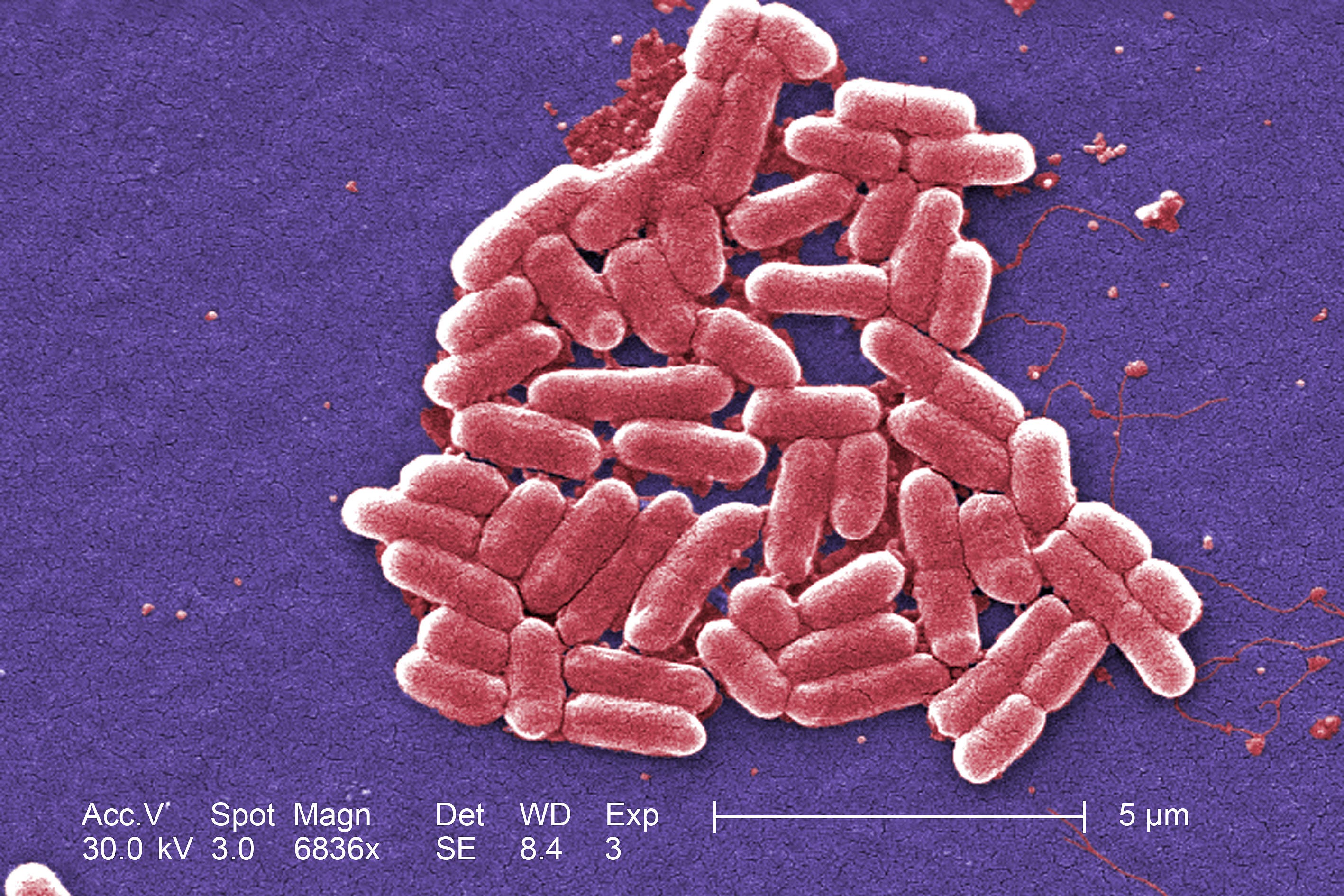

The bacteria, E. coli, is commonly found in the human gut. Most strains of E. coli are harmless; however, if the bacterium gets into the bloodstream due to a weakened immune system it can cause infections, ranging from mild to life-threatening.

The two strains of E.coli looked at by the researchers are the leading cause of UTIs and bloodstream infections across industrialised countries. They also suggest targeting these bacteria could reduce antibiotic medication use in industrialised countries.

Using genomic surveillance data from countries including the UK, Norway, Pakistan and Bangladesh researchers tracked the different strains of E.coli.

Previous premilitary research suggests that two strains E.coli can produce a substance called colibactin which plays a role in the development of cancers of the urinary tract and have been linked to tumour samples from colon cancer patients.

Comparing the rates of these strains with cancer rates they found industrialised counties where these strains circulated also had higher levels of bowel, bladder and prostate cancers.

However in countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan these strains of E.coli were much rarer as were incidences of bowel, bladder and prostate cancers.

The paper suggests further large-scale investigation is needed, including wide-spread tumour sampling, to clarify the role of colibactin in cancer.

Dr Tommi Mäklin, first author of the study, from the University of Helsinki and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “E. coli can be found around the world, in many different forms, and understanding how strains of this bacteria impact humans differently can give us a more complete picture of health and disease.

“Having access to global genomic data on which strains are found in an area can uncover new trends and possibilities, such as strains in industrialised countries potentially being linked to the risk of certain cancers. We also need to keep ensuring that countries and regions around the world are included in genomic surveillance research so that everyone benefits from new discoveries.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks