Scientists create 'artificial womb' that could save premature babies' lives

Researchers rule out possibility new device will spell end of conventional pregnancy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Extremely premature babies could be kept alive in future using an “artificial womb” that scientists plan to test in humans after a successful study involving unborn lambs.

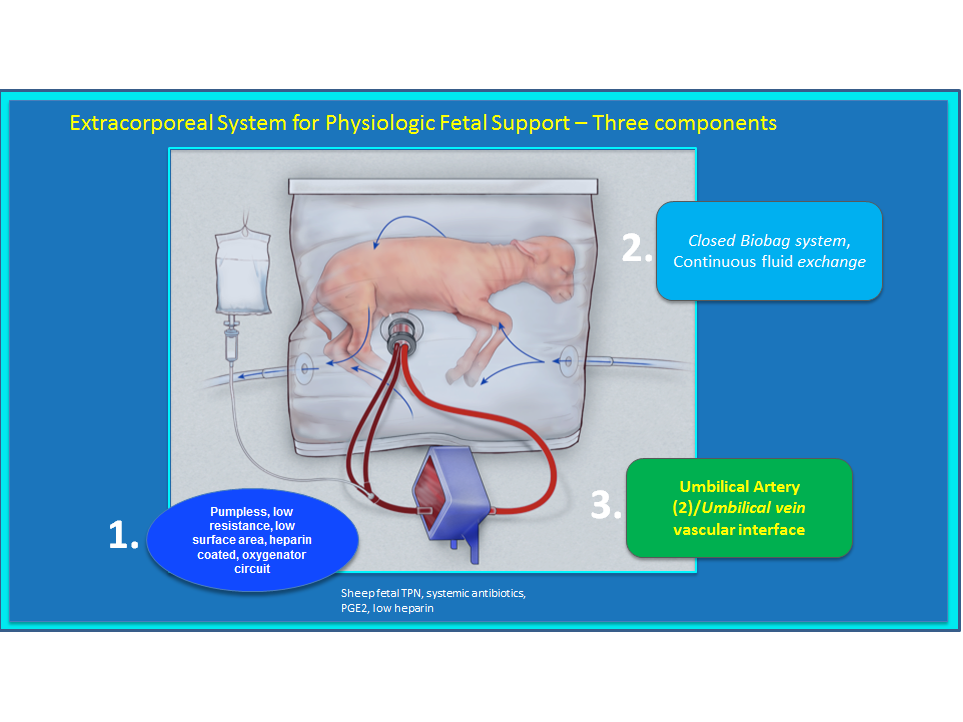

A plastic bag filled with artificial amniotic fluid – the nutrient-rich liquid that sustains a foetus in the womb – allowed foetal lambs to develop at an age equivalent to 23 weeks in humans.

Human infants born at 23 weeks have just a 15 per cent chance of survival, according to pregnancy research charity Tommy’s. This rises to 55 per cent at 24 weeks, while babies born at 25 weeks have an 80 per cent chance of survival.

Premature babies are often placed in incubators to help keep them warm, but the new invention closely replicates conditions in a real womb, scientists at the Center for Fetal Research at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia have said.

“This system is potentially far superior to what hospitals can currently do for a 23-week-old baby born at the cusp of viability,” said Dr Alan Flake, the Centre’s director.

“These infants have an urgent need for a bridge between the mother's womb and the outside world. If we can develop an extra-uterine system to support growth and organ maturation for only a few weeks, we can dramatically improve outcomes for extremely premature babies.”

Inside the device, the infant's own heart circulates blood through the umbilical cord into an external gas-exchange machine taking the place of the mother's placenta, while synthetic amniotic fluid enriched with nutrients flows in and out of the temperature-controlled, near-sterile “biobag”.

No mechanical pump is used, because even gentle artificial pressure could fatally overload an underdeveloped heart.

The researchers believe their new system could be ready for human trials in three to five years, but stress there is no question of using the system to replace a mother's womb at earlier stages of development – which could raise fears of sci-fi technology and the end of conventional pregnancy.

Six pre-term lambs were used in tests of the most recent version of the “extra-uterine support device”, which evolved from a glass tank to the biobag design over a period of three years.

Animals “breathed” and swallowed normally, opened their eyes, grew wool and developed properly functioning nerves and organs, said the researchers writing in the journal Nature Communications.

The lambs remained in the “womb” for up to a month. While most were humanely killed to allow analysis of their brains, lungs and other organs, a few were allowed to survive and were bottle-fed.

“They appear to have normal development in all respects,” said Dr Flake as one of the survivors reached a year old.

But Dr Flake said there was no technology “even on the horizon” that could replace a mother's womb at the earliest stages of foetal development. “There's a lot of sensationalistic conversation about supporting humans artificially from embryo forward,” he said.

“I would be very concerned if other parties wanted to use this device to try to extend the limits of viability.”

Every year in the UK 60,000 babies – one in nine – are born prematurely, requiring special hospital care.

At infant prematurely born at 23 weeks weighs less than 600 grams. There is a high likelihood of lifelong disability among those that do survive, who have a 90 per cent probability of suffering chronic lung disease or other effects of being born with immature organs.

A major technical hurdle still to be crossed is downsizing the system to make it suitable for human infants, which are a third of the size of the lambs used in the study.

Expert Professor Colin Duncan, from the University of Edinburgh, said: “This research isn't about replacing the womb in the first half of pregnancy. It is about the development of new ways of treating extremely premature babies.

“The researchers supported the growth and development of extremely premature foetuses within a bag of fluid where the foetus pumps its own blood through an artificial placenta.

“This is a really attractive concept and this study is a very important step forward. There are still huge challenges to refine the technique, to make good results more consistent and eventually to compare outcomes with current neonatal intensive care strategies.”

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have grown a miniature “womb lining” in a lab which they hope can provide new insights into the early stages of pregnancy, when the placenta is established.

“Events in early pregnancy lay the foundations for a successful birth, and our new technique should provide a window into this events,” said Professor Graham Burton, director of the university’s Centre for Trophoblast Research.

Additional reporting from Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments