UK girl first in world to have deadly superbug infection treated with bacteria-hunting GM viruses

'We were at the point where there was no other hope, they said she wasn't going to leave the hospital and had less than 1 per cent chance of survival'

A British teenager with cystic fibrosis has become the first person in the world to be treated with genetically engineered, bacteria-hunting viruses, after developing a deadly infection.

Two years ago Isabelle Holdaway, now 17, was fighting for her life in Great Ormond Street Hospital (Gosh) following a lung transplant and antibiotics were no longer having any effect.

"We were at the point where there was no other hope, they said she wasn't going to leave the hospital and had less than 1 per cent chance of survival," Isabelle's mother Jo Holdaway told The Independent.

But after being treated with a cocktail of bacteriophages – viruses which are specialised to kill the bacteria but not infect human cells – she is now back taking her GCSEs and learning to drive.

"She's doing all the things you should be doing at 17," Ms Holdaway added.

“Everyone said don’t get your hopes up, it’s totally experimental. If I was a religious person I would have been praying but we just had to hope that it arrived in time for Isabelle to benefit."

"Nobody else would have had access to this had they not been in this dire, near death situation - she is a lucky, lucky girl."

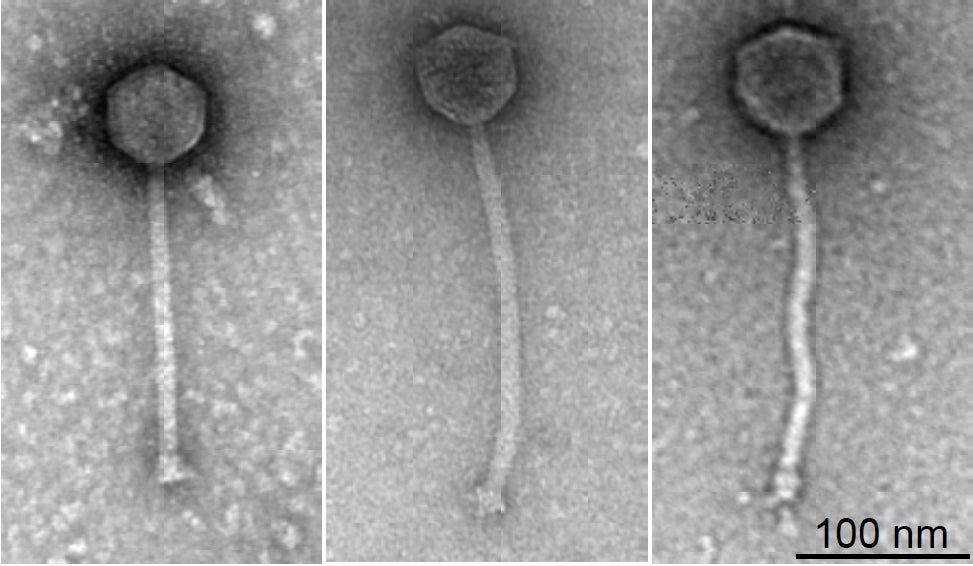

While phage therapy has been a concept for nearly a century, it has had limited use because each virus is tightly evolved to kill a particular bacteria strain and not all are lethal enough to be effective.

But Isabelle’s case is the first to show how genetically engineering these viruses could make them more effective.

This could make it an important future tool in the battle against drug resistance, which health leaders warn could push medicine back to the “dark ages”. While significant research will be needed before it becomes a mainstream treatment this gives proof of concept.

“This is the first person who has been treated for a mycobacterium infection with phage therapy, that we’re aware of,” respiratory paediatrician Dr Helen Fisher told The Independent.

The mycobacteria are a group which include tuberculosis-causing strains and which are increasing worry because of their drug resistance, but are a "particular problem in cystic fibrosis".

In Isabelle’s case, the infection at the site of her surgical wound, had spread to her liver and her lungs and after nine months in hospital she was no longer responding to antibiotics.

“She was incredibly sick,” said Dr Spencer, who is also one of the senior authors of the paper published in the journal Nature Medicine.

“She had fulminant [acute] liver failure... She was pretty much bed bound, wasn’t eating at all, we were having to feed her intravenously.”

“Isabelle’s parents knew we were trying to work on this phage therapy, so when the time came that we had no other conventional therapies to use and ongoing signs of infection – they were desperate for other options.”

Isabelle’s parents had read about phage therapy in a different infection and proposed it as an option to Dr Spencer.

This led the Gosh team to send samples of Isabelle’s infection, and another similarly infected patient, to microbiology expert Professor Graham Hatfull, at the University of Pittsburgh.

The university has one of the largest collections of bacteriophages in the world, with more than 15,000 strains identified and catalogued by researchers, though these were never intended for medical use.

“We were sent a few strains, from London, and set about testing whether the phages in our collection would be able to infect these particular bacterial strains,” Professor Hatfull said.

But despite a shortlist of 100 likely candidates there was only one strain – dubbed “Muddy” – which was a natural born killer. This forced them to go a step further and engineer two other likely candidates to beef up their lethality to the mycobacterium.

This cocktail combination also minimises the chances of the bacteria adapting to withstand any one attacker.

In June 2018 Isabelle began twice daily infusions of the phages, receiving billions of viruses at a time, and six weeks later the infection had disappeared from her liver.

While pockets of skin infections remain her doctors hope the combination of phage therapy and antibiotics will eventually clear it.

However they stress that there are significant limitations to phage therapy becoming a mainstream option. The second patient Professor Hatfull and colleagues had been investigating died just a month before they identified a potential phage treatment.

“Antibiotics are very effective, but they’re a blunt instrument,” Professor Hatfull told The Independent.

“With phages it’s the opposite end of the spectrum. They’re very specific, it’s a targeted strike, you’re not going to affect the rest of the microbiome and they’re low toxicity, because they don’t infect human cells.”

“But it’s a double edged sword, because they may target the strain infecting patient number one, but patient two or three, may have the same species of bacteria but the strain can vary to such an extent that it doesn’t work.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks