Alzheimer's patients could recover 'lost' memories, scientists say

Research on mice suggests disease does not wipe memories, but makes them harder to access

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.New drugs could one day be developed to help Alzheimer’s patients recover memories believed to be lost forever, according to scientists who have reawakened forgotten memories in mice.

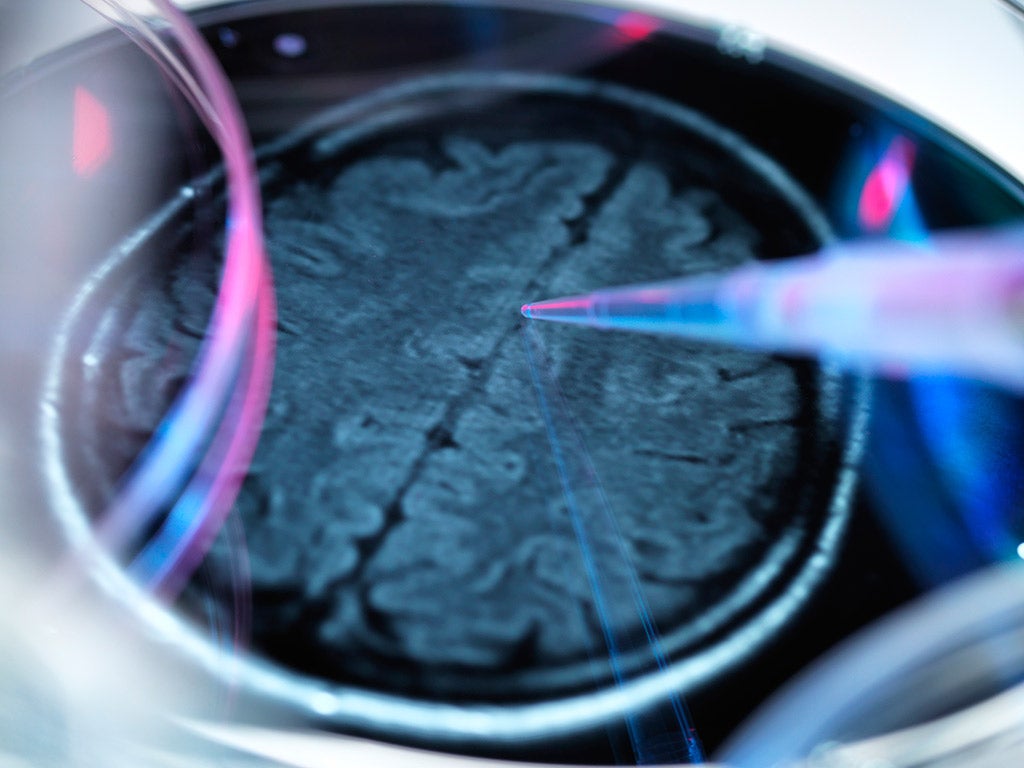

Memory loss in people with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is caused by the build-up of a toxic plaque in the brain that destroys nerve cells.

This sticky substance, created by a protein called amyloid beta, is thought to completely erase memories – causing progressive amnesia that can be distressing for both patients and their families.

But new research suggests it is still possible to recall these memories, because they are not completely wiped by the disease, but just made harder to access.

Scientists at Columbia University in New York used lasers to reveal that mice with a condition similar to human Alzheimer’s were calling up the wrong memories – a phenomenon also seen in people with dementia, whose recollections of the past can become muddled and incorrect.

However, when the brain cells that store memories were stimulated in the Alzheimer’s mice, they appeared to remember a lemon smell they had previously ‘forgotten’.

Listening to music sometimes has a similar effect for Alzheimer’s patients, helping to unearth long-lost memories, suggesting they may not disappear completely.

“These results indicate that [the memory] still exists and has not degraded, but is difficult to access for memory retrieval or behavioral expression when Alzheimer’s Disease is present,” said the study, published in the journal Hippocampus.

“The mice may be recalling an incorrect memory, as the wrong cells – or possibly a new ensemble that may have different mnemonic properties than the original ensemble – are being activated.”

Ralph Martins, an Alzheimer’s expert unconnected to the study, said the research “makes sense” as music appears to have the power to retrieve memories of the past in people with dementia.

“It has the potential to lead to novel drug development to help with regaining memories,” Professor Martins, from Edith Cowan University in Australia, told the New Scientist.

Dementia, which mainly affects older people, causes a deterioration in memory, thinking and behaviour and can impede someone’s ability to perform everyday activities.

It affects around 47 million people worldwide, predicted to grow to 75 million by 2030, and has overtaken heart disease as the leading cause of death in England and Wales.

The Columbia scientists carried out their experiment on two sets of mice, one with the Alzhiemer's-like condition, and the other with healthy brain cells.

Both groups were genetically engineered so their neurons glowed yellow when new memories were created, and red when old memories were recalled.

They exposed both sets of mice to a lemony smell, then gave them an electric shock. A week later, they tested these memories by releasing the same lemon scent.

While the healthy mice froze in fear, half of the mice with Alzheimer's disease did not, and the neurons that glowed red were not in the same place as the yellow ones – unlike in the healthy mice, where they overlapped.

When a blue laser was shone down a fibre optic cable into the brains of the mice with Alzheimer's, stimulating the part of the brain where the memory was stored, they froze, indicating these memories had been 'revived'.

While it is too early to say whether the same effect would happen in humans, Professor Martins said with further research, the findings could be revolutionary.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments