How the pandemic created a generation of ‘grey area’ drinkers

The term ‘Grey area drinking’ describes people who consume more than a moderate amount of alcohol but don’t meet the criteria for dependence, writes Ian Hamilton

Increased drinking during the pandemic has created a group of people who don’t see themselves as alcoholics but have difficulty abstaining from alcohol for any length of time. This group, starting to be called grey-area drinkers, are at risk of alcohol-related health problems.

The relatively new term “grey-area drinking” describes people who consume more than a moderate amount of alcohol but don’t meet the criteria for dependence. Although they might not drink every day or have a drink first thing in the morning (the widely held view of an alcoholic) they are likely to be preoccupied with alcohol and have difficulty giving up. Many of these people don’t view themselves as in need of help.

Any widespread increase in levels of alcohol consumption matters. While most people are familiar with the risk of dependence, there are a range of severe physical health problems associated with increased alcohol consumption that they are not so aware of. These include heart disease and a range of cancers, including bowel and breast.

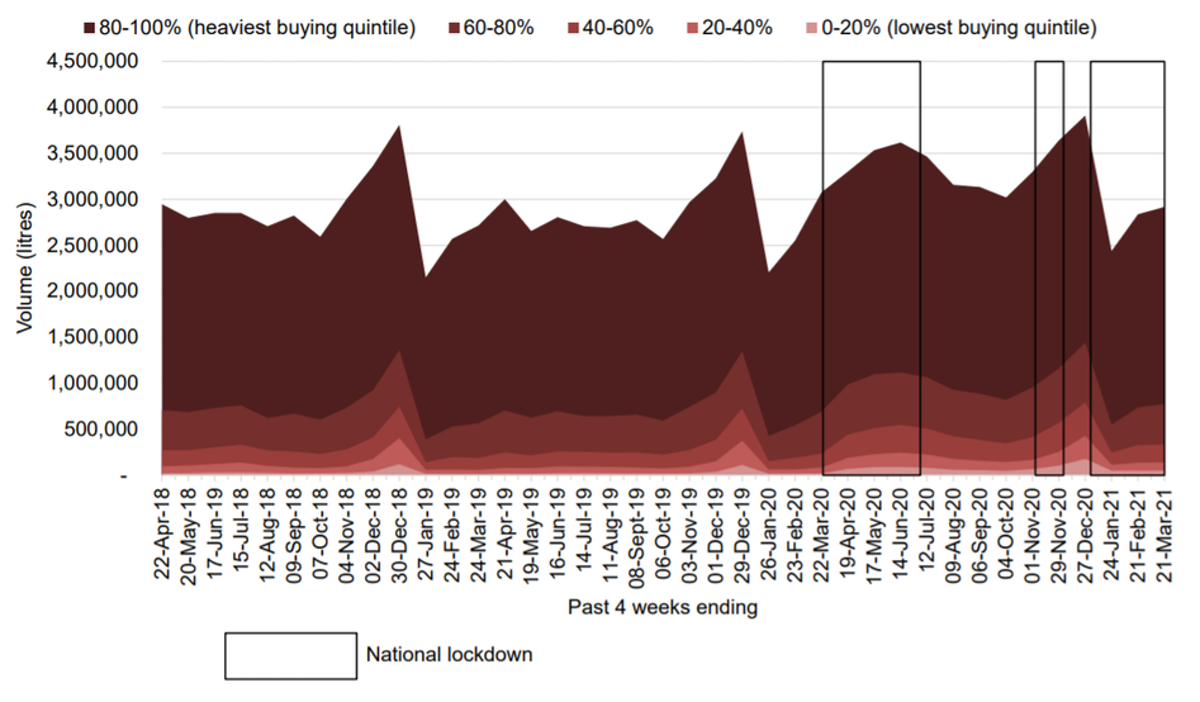

Although overall consumption of alcohol has been slowly declining in recent years there is emerging evidence that some people have increased their consumption. The heaviest-buying segment of the population increased their purchasing by 5.3 million litres of alcohol (+14.3%) from 2019 to 2021. At the same time physical harm from alcohol has been increasing, with a significant rise in hospital admissions and alcohol-related deaths.

Public Health England collated the results of 18 surveys of self-reported alcohol consumption during the pandemic. Between 11% and 37% reported drinking less but between 14% and 26% of people reported drinking more than usual. This is especially concerning given that we know most people underestimate how much they drink by up to 40% in these surveys.

Pubs were closed during the pandemic, so drinking at home increased. This may have encouraged drinking in large quantities as people tend to pour larger measures of alcohol when drinking at home compared to the measures they are given in bars.

Evidence found that those who experienced stress during the pandemic increased the amount of alcohol they drank and how often. One international study exploring alcohol consumption during periods of self-isolation found that it was British drinkers who were most likely to increase the amount of alcohol they consumed – which they say was due to elevated levels of Covid-related stress.

These surveys found a noticeable increase in consumption for some once the pandemic began. Those who were drinking below the government’s recommended weekly limits continued to stay within these limits. However those who were already drinking above the 14 units a week increased their consumption.

Current UK guidance suggests no more than 14 units of alcohol should be consumed in a week.

Levels of hazardous drinking are considered to be more than 50 units a week for men and 35 units for women. Evidence suggests that there was a 59% increase in those reporting drinking at these levels compared to before the pandemic.

Some argue that the alcohol industry embraces the perception that the majority of people drink responsibly. This has been one of the industry’s main arguments for resisting greater regulation. The industry points to the need for personal responsibility rather than corporate responsibility, although they fail to define what responsible drinking is. This shifts the onus onto the individual to make a change to their drinking habits rather than requiring the industry to make changes to its marketing or promotion techniques.

At a time when there is a clear need to tackle increased alcohol consumption, funding for specialist treatment and support has been withering. Some sections of the alcohol industry were encouraged to increase marketing spend as it would be more effective than ever. Some analysis shows that alcohol companies have also used lockdown for targeted social media activity. And the alcohol industry’s multi-million pound spend on marketing is huge, compared with the budget for public health messages: a truly David-and-Goliath struggle.

There has been little mention of alcohol or our unhealthy relationship with it during the pandemic by the government. For instance, off-licences were deemed to be essential services and stayed open during lockdown. The alcohol industry has proved to be adept at influencing government policy in its favour.

As treatment budgets are cut industry marketing increases and there is nothing to suggest that there will be any reduction in demand for hospital treatment due to alcohol or, sadly, coroners recording yet more alcohol-related deaths.

Ian Hamilton is an associate professor of addiction, at the University of York. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks