Governor was warned of would-be regulator's ties to utility

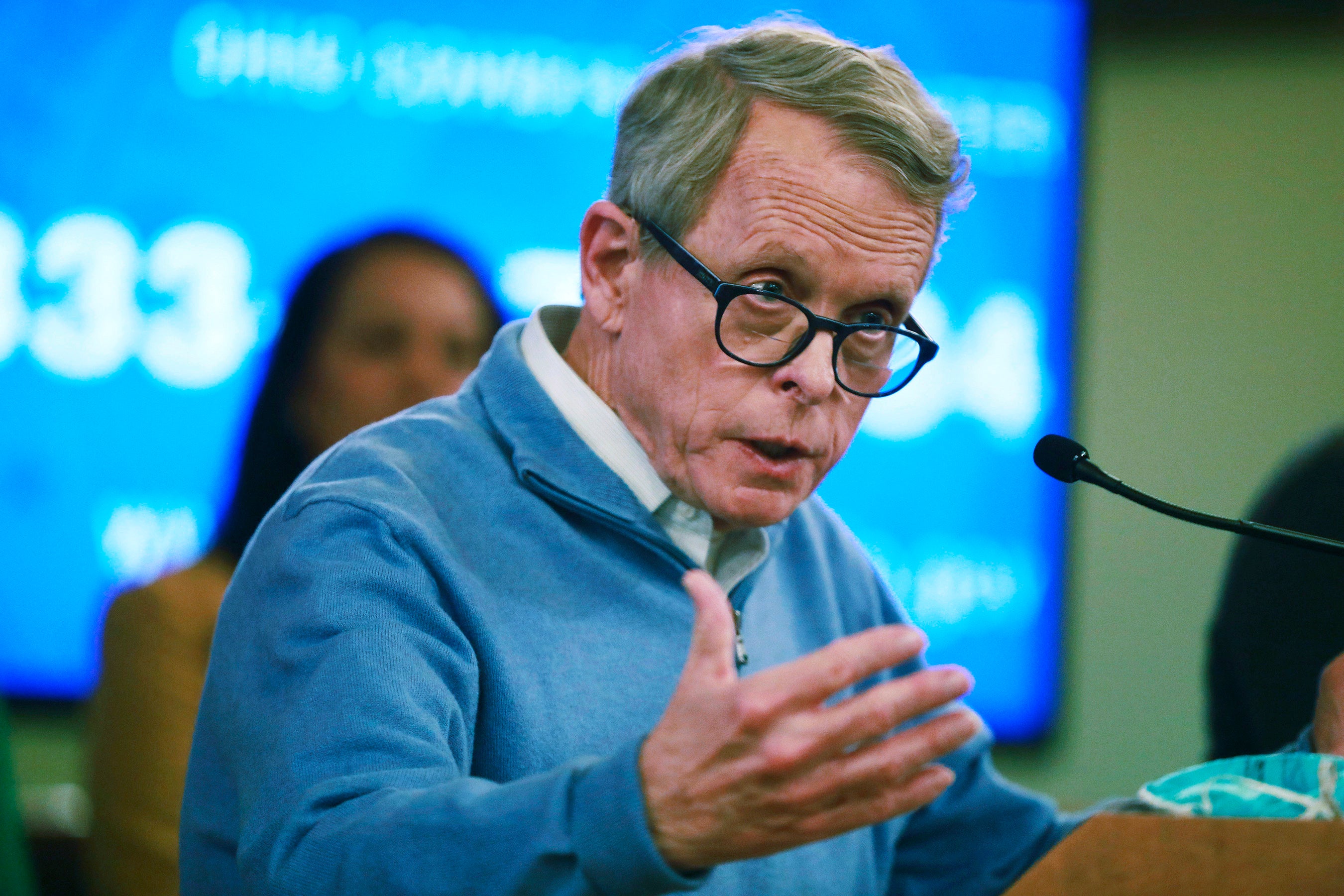

A previously undisclosed document shows Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine disregarded a last-minute plea from Republican insiders in selecting a top Ohio utility regulator now under legal and financial scrutiny

Gov. Mike DeWine disregarded cries of alarm in early 2019 from consumer and environmental advocates, concerns echoed in a previously undisclosed last-minute plea from GOP insiders, when he was selecting the state's top utility regulator — a man now under scrutiny as a wide-ranging bribery and corruption investigation roils Ohio.

Nearly two years later, the Republican governor continues to defend his choice of Samuel Randazzo as the powerful chair of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, and many of those early critics insist it was a mistake to disregard their concerns.

“We understood that he had worked for manufacturing companies; we also understood that he had done work for FirstEnergy,” DeWine said this week in an interview with Associated Press reporters. “Those were all things that we knew. He was picked because of his expertise and vast knowledge in this area. So that’s pretty much what we knew, so there was no secret.”

Randazzo, 71, had deep business ties with the state’s largest electric utility and had long been hostile to the development of wind and solar power, making him unsuitable for the role, critics warned early on.

In mid-November, FBI agents searched Randazzo’s home in Columbus. The utility, FirstEnergy Corp., revealed several days later in a quarterly report that it was investigating a payment of about $4 million that top executives made to the consulting firm of an Ohio government official meeting Randazzo’s description.

DeWine said this week that Randazzo did not disclose, and the governor did not know of, the FirstEnergy consulting payment until the company reported it to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. FirstEnergy's quarterly report said it had not determined if the funds “were for the purposes represented within the consulting agreement.”

The first-term governor's latest comments are largely in line with his initial reaction to FBI interest in Randazzo. A day after federal agents searched Randazzo's home Nov. 16, DeWine told reporters: "I hired him. I think he’s a good person. If there’s evidence to the contrary, we’ll act accordingly."

Randazzo resigned days later, citing in a letter to DeWine that “events and news of this week have undoubtedly been disturbing or worse to many stakeholders.” DeWine responded by thanking Randazzo, saying, “He has done very, very good work as chair.”

DeWine told the AP on Tuesday that he has no concerns about the swift selection process by which Randazzo traveled from planning for semi-retirement to being appointed to the commission during the five weeks of DeWine's new administration.

During that time, according to several sources with personal knowledge, fellow Republicans tried to warn DeWine, and a dossier detailing Randazzo's questionable ties to FirstEnergy was prepared by interested parties and delivered to DeWine's chief of staff, Laurel Dawson. Dawson discussed its contents with a group on Jan. 28, 2019, but rejected their warnings, the sources said. The people spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of professional repercussions.

DeWine said he has “great confidence” in Dawson, who has worked for him since 1983 and whose husband, Mike, has done communications work for FirstEnergy in the past. A request for direct comment was sent Thursday to Dawson. Continued attempts to reach Randazzo for comment have been unsuccessful.

“Look, the buck stops with me,” DeWine said. “I’m the one who ultimately makes those decisions.”

The dossier, a copy of which was obtained this week by the AP, warned that publicly available documents suggested that Randazzo had “opaque, undisclosed financial ties that should be fully examined and made public.”

Among those were debts that a former FirstEnergy subsidiary acknowledged in its 2018 bankruptcy case owing to two Randazzo-owned companies. The memo said Randazzo used one of the companies to attack adversaries of the subsidiary and to buy personal, commercial and industrial properties for himself in Ohio. Records reviewed by the AP back up the property claims.

DeWine said Tuesday that there was nothing in the information on Randazzo provided to him or his staff that was new, noting that Randazzo has spent the past four decades as a lawyer and lobbyist specializing in Ohio energy issues.

“I’m sure that people, not just in our administration but people around Capitol Square, all knew that he had done work for a lot of different people,” he said. “Sam Randazzo has been around for a long, long time.”

The governor said Randazzo's ability to clearly explain energy issues and to lay out both sides of an argument were among his key assets.

Todd Snitchler, former chair of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, said that for DeWine to appoint someone with a such a long history with FirstEnergy “suggests that the administration failed to consider the implications of the appointment or simply ignored the warnings.”

“Either way, this decision encourages public distrust at a time when many believe the government doesn’t work for them,” Snitchler said Wednesday in a statement to the AP.

He and other critics find DeWine's seemingly steadfast support of Randazzo puzzling at this point, given what has occurred since U.S. Attorney David DeVillers arrested Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder and four others on July 21 for their alleged roles in a $60 million bribery scheme secretly funded by FirstEnergy.

Prosecutors allege Householder used his portion of the money to elect supporters to the Ohio House, win back the speakership and push through a $1 billion bailout to save two aging and financially struggling nuclear power plants operated at the time by FirstEnergy Solutions, which was a subsidiary at the time, filed for bankruptcy and has since changed its name to Energy Harbor.

Neil Waggoner, of the Sierra Club, said Randazzo “was not an impartial regulator” and criticized DeWine's “absence from the conversation” about the tainted bailout bill and so far unsuccessful efforts to repeal it.

“(The governor) hasn't been holding the Legislature's feet to the fire on this,” Waggoner said. “He's been on the sidelines, The only activity we've seen from the DeWine administration on energy policy is to appoint Randazzo and completely defer to him.”

Rob Kelter, of the Environmental Law & Policy Center, which opposed the bailout bill, said DeWine is accountable for appointing Randazzo while being aware of his relationship with FirstEnergy.

“I think what it says is that he was putting the interests of FirstEnergy above the interests of FirstEnergy customers," he said.

___

Gillispie reported from Cleveland.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks