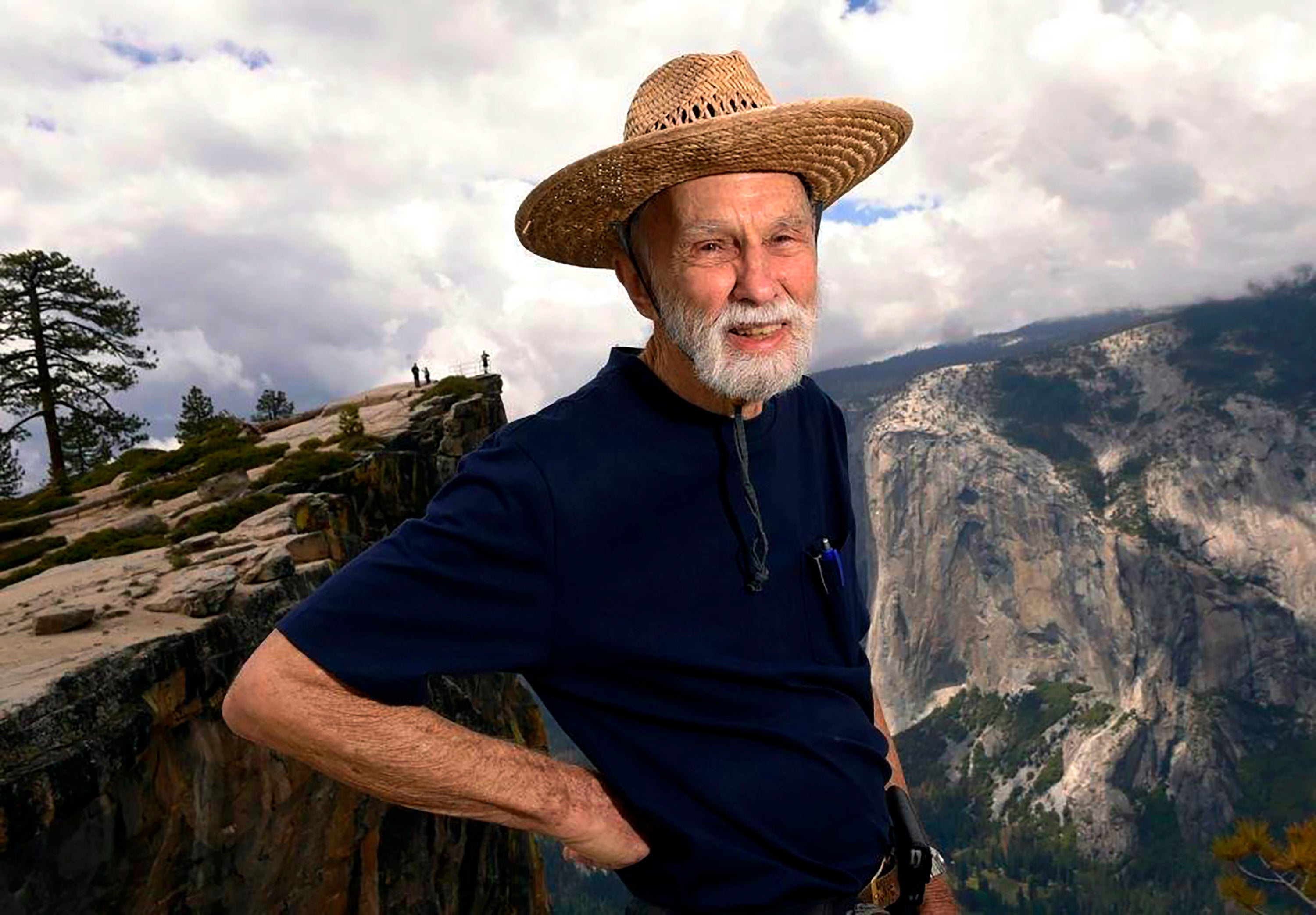

George Whitmore, legendary climber of El Capitan, dies at 89

George Whitmore, a member of the first team of climbers to scale El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, has died at age 89

George Whitmore, a member of the first team of climbers to scale El Capitan in Yosemite National Park and a conservationist who devoted his life to protecting the Sierra Nevada, has died. He was 89.

Whitmore died on New Year’s Day from complications caused by COVID-19, said his wife, Nancy She said Whitmore, a cancer survivor, was extremely careful about wearing a mask and his family doesn't know where he contracted the virus. He tested positive for COVID-19 on Dec. 13, after developing a rattling but occasional cough and subsequent fever. He died in a Fresno rehabilitation facility from damage to his lungs about a week after being released from a hospital, his wife of 41 years said.

Friends, family, colleagues and fellow climbers mourned the passing of a legend in the world of rock climbing and the last surviving member of the trio that was the first to reach the top of El Capitan on Nov. 12, 1958. Ascending the 3,000-foot (914-meter) sheer granite rock wall that now attracts climbers from around the world was, at the time, a feat considered out of human reach.

In 2008, Whitmore gathered with climbers from around the world at Yosemite to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his ascent with Wayne Merry and Warren Harding, who died in 2002. Merry died in 2019.

Whitmore, then 77, told AP they didn’t realize at the the time “how special” their climb of the sheer rock formation would be. It took them 47 days over 16 months to complete the climb. They set fixed lines and rappelled down, then used the ropes to return to the same point later.

“They were pioneering techniques that didn’t exist at the time. They were kind of inventing the sport of big wall rock climbing,“ said Daniel Duane, author of “El Capitan: Historic Feats and Radical Routes.”

El Capitan now has dozens of routes, scaled by some in fewer than three hours. But at the time, it seemed “utterly outside the bounds of the possible,” Duane said. Whitmore and his team plotted a path that came to be known as “The Nose.”

“They created this kind of pilgrimage path in the sky that, to this day, every climber on Earth wants to someday walk,” Duane said.

In interviews over the years, Whitmore spoke of his ascent with humility. Mountain climbing was a lifelong passion, but he often said he considered his work in conservation to be his greatest accomplishment.

A pharmacist by trade, Whitmore retired in the 1970s to focus on conservation, his wife said. He was involved with the Sierra Club in local, state and national capacities, including serving as a chairman of the Tehipite Chapter based in Fresno.

It was during a Sierra Club outing in the 1970s that he met his wife, Nancy, who was impressed with his knowledge and intellect.

“I was like, wow, this guy is impressive,” said Nancy, 76. They married in 1979.

“He was passionate about saving California wilderness,” she said. “He was a constant salesman, not for himself, but for the forest and the wilderness.”

Whitmore helped establish the Kaiser Wilderness in 1976 and the California Wilderness Act of 1984, which added 1.8 million acres into the National Wilderness Preservation System. He helped protect lakes and block dam projects and proposed highways and also helped prevent The Walt Disney Company from developing a proposed ski resort at Mineral King in the 1960s and '70s. It was stopped after sustained opposition by the Sierra Club and other preservationists and the valley subsequently became part of Sequoia National Park.

“A lot of times what it takes is someone like George who sticks to his guns and doesn’t back down from a fight that he knows is the right thing to do,” said Gary Lasky, current chairman of the Sierra Club’s Tehipite Chapter.

Lasky recalled Whitmore as a dignified man who was modest about his achievements but also tenacious and deliberate; he was able to see both the big picture and focus on crucial details, skills that served him as an environmentalist and a climber.

“He never bragged. He is a man of a few words. He would think and then speak,” said Lasky. “He was very gracious to everyone. He was beloved.”

Whitmore actively attended Sierra Club meetings until the pandemic started and the meetings went online, his wife said.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks