Swiss-backed project aims to avert new 'Cold War' in science

Switzerland’s foreign minister says concerns about a “new Cold War” over science and technology are a major reason behind the creation of a new think tank that looks out for future advances and development so that the whole world can benefit and not just rich countries

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Switzerland’s foreign minister says concerns about a “new Cold War” over science and technology are a major reason behind the creation of a new think tank that looks out for future advances and development — so that the whole world can benefit, not just rich countries.

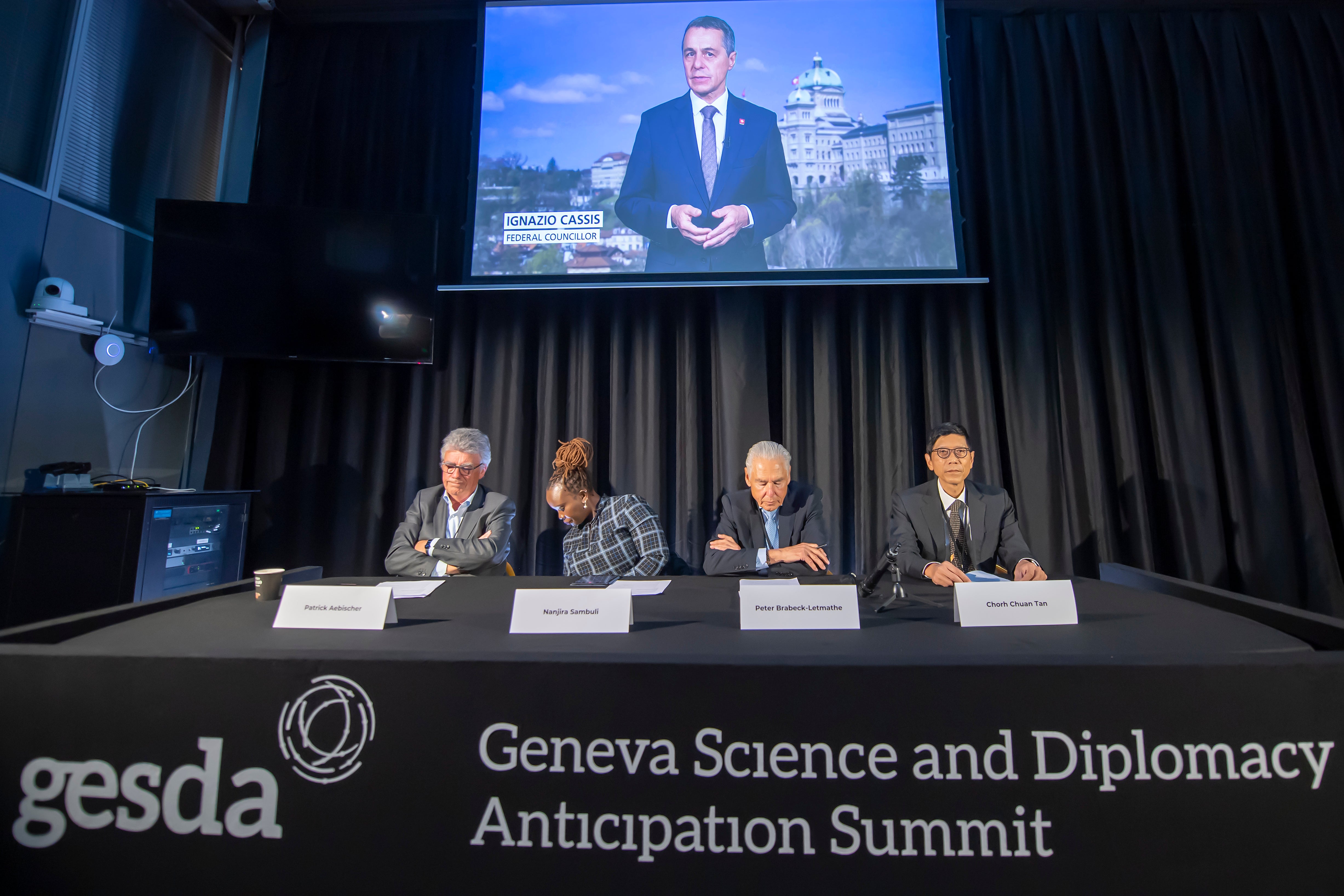

Ignazio Cassis delivered a video message for the inaugural “summit” on Thursday and Friday of the Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator, or GESDA, a Swiss government-backed project that aims to bridge government policy and science in an international city known for both.

“There is a growing feeling that a new Cold War is about to be fought over science and technology, and the power they confer to the states that master them,” he said. GESDA, which brings together hundreds of scientists and policymakers worldwide, would serve as an “honest broker” that helps spread the benefits of science to countries rich and poor, he said.

“What we are trying to achieve with GESDA is new, and hence, difficult: To link anticipation that looks far ahead, with action that is immediate is a major challenge in itself,” Cassis said.

While conceived in 2019, GESDA has started to look prescient during the COVID-19 pandemic that caught many governments off guard, drew an uncertain or unclear response by health policy makers like the Geneva-based World Health Organization, and has exposed gaping inequality between the rich countries that have wide access to vaccines — and poor countries that don’t.

Pandemic preparedness projects and monitoring bodies have popped up in places like Europe and the United States since the outbreak, and the Biden administration has shown interest in the GESDA project -– and its focus on anticipating future trends and developments.

Alondra Nelson, deputy director for science and society for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, noted U.S. President Joe Biden has spoken about today’s moment “of great peril and great promise,” and she said governments should be bold about both innovation and partnership.

“I think that the Anticipator — anticipatory frame — is a fantastic possibility for working this through,” she said by videoconference from Washington on Thursday. “Anticipation is filled, of course, with both enthusiasm and yet unease.”

Dr. Jeremy Farrar the director of the Wellcome Trust charity and a key player in international health policy, has lined up with GESDA and told reporters on Thursday that while science has made great strides, action must be taken because otherwise “scientific advances will increasingly be available to a small elite in the world — and not to everybody.”

Last week, GESDA and XPrize announced the creation of a prize for developments in quantum computing. But GESDA, a self-dubbed “do tank,” has far broader ambitions such as helping set up a global court for scientific disputes and a Manhattan Project-style effort to rid excess carbon from the atmosphere.

It brings together hundreds of U.N. officials, Nobel laureates, academics, diplomats, advocacy group representatives and members of the public. Backers include Swiss universities and Geneva-based CERN — home to a lab with the world’s largest atom smasher.