Kevin Harcombe: Teachers are just no good at going on strike

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

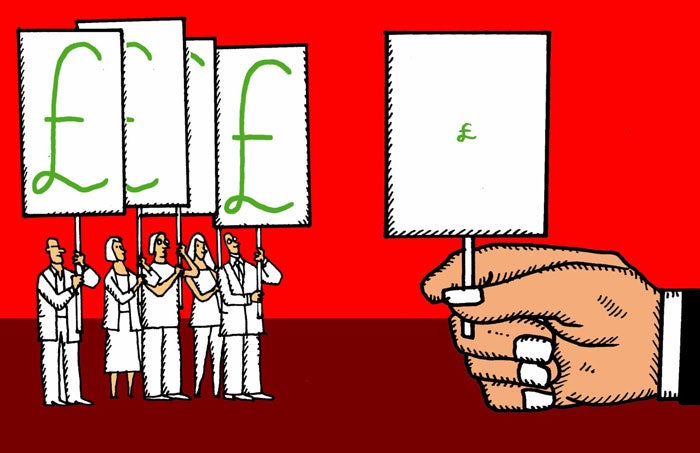

Your support makes all the difference.No sooner had Gordon Brown begun talking tough about public-sector pay restraint, than the "threat of strike" headlines started to appear. One television hack even used the phrase "winter of discontent", with an almost nostalgic, wistful tone in his voice. The National Union of Teachers, on cue, said it would ballot members on a one-day strike if awarded a below-inflation pay rise. Since the announcement of a 2.4 per cent rise (more than police and nurses) they have continued to threaten a "robust response".

Should teachers be surprised at a 2 per cent-plus settlement each year for the next three years? Not really – we are currently in a two-year deal anyway and belt-tightening has long been forecast. Should we be angry? Possibly – but less angry than nurses and the police. Should we strike? On pragmatic grounds alone, no, for teachers are to strike action what Eddie the Eagle is to ski jumping.

I am old enough to have participated in the last national teachers' strike in 1987 – freshly graduated from still radical Sussex University and, as befitting a boy from the self-styled Socialist Republic of Liverpool, a solid union man. As a newly qualified teacher, my salary was so meagre I had to supplement it by teaching guitar after school. Moral courage duly screwed to the sticking place, I informed my head, a true-blue Tory gent, that I would be withdrawing my labour in solidarity with my union brothers and sisters. Sadly, when it came to the big day, solidarity, like Elvis, had left the building and I was the only teacher in my school taking action. I hastily altered my placards to "One out – One Out!" and "The worker (singular) united will never be defeated!"

To be an effective striker you need public sympathy (like the nurses) or alternatively, the public's testicles in your grasp (like the power workers). Teachers have public sympathy to an extent, partly because we seldom take industrial action, but do we have a grip on the nation's testes? Hardly. A teachers' strike would cause some problems with child care, but homes would not be plunged into the dark and cold – bread would still be on the table, petrol in the car. For parents, it would be irritating (there goes the sympathy), but not a testicle-crushing moment. For most children it would simply be an extra holiday.

The prerequisite for successful industrial action, however, is worker unity and teachers are split between four competing unions, including one (Professional Association of Teachers) with a no-strike clause. Moreover, while teaching unions continue to grow (mainly for teachers' insurance and legal cover) they suffer from what academic researchers quaintly call "the problem of membership non-participation", otherwise known as apathy.

This must stem in part from rank and file members feeling fairly satisfied with their lot. Between 1997 and 2005 teachers' pay increased by around 15 per cent even after taking inflation into account. The upper pay scale, introduced in 2000, gave classroom teachers with at least six years' experience the opportunity to receive an additional £2,000 per annum (then approximately 8 per cent of salary) through performance-related pay.

This was effectively a stealth pay award, the Government's cunning plan to circumvent hostile headlines in the Daily Mail by portraying it as a "something for something" deal. For all the supposed rigour and bureaucracy of this system, you only had to be a "satisfactory" teacher to get it. Indeed, 95 per cent of those who completed their 12-page assessment to "cross the threshold" were successful. Now a teacher can stay in the classroom, take on no extra responsibilities and still earn £35,000 after 10 years. Teachers have also gained guaranteed planning, preparation and assessment time since 2005 – a previously undreamt of enhancement to conditions equating to 10 per cent of the week out of class. Both innovations came about by a willing government working with (mostly) willing unions.

Nevertheless, if you are several years away from the upper pay scale and still paying off student loans through second jobs, a 2.4 per cent increase is not much of a gain when rents and fuel costs are rising faster. These junior teachers are the school leaders of tomorrow and too many leave after three years. If the teaching unions wanted to champion a cause, arguing for a rise weighted towards retaining less experienced teachers might get public sympathy.

The Government will hope to have spiked the guns of discontent by letting pundits assume a 2 per cent rise, then announcing nearly 2.5 per cent – just above its measure of inflation. It remains to be seen how clever the teaching unions are with their response.

The writer is head teacher of Redlands Primary, Fareham, and the National Primary Head of the Year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments