Good works: How Scotland's poshest school justifies its charitable status

In Scotland, revised rules on charitable status have been spelt out. Are there lessons for England?

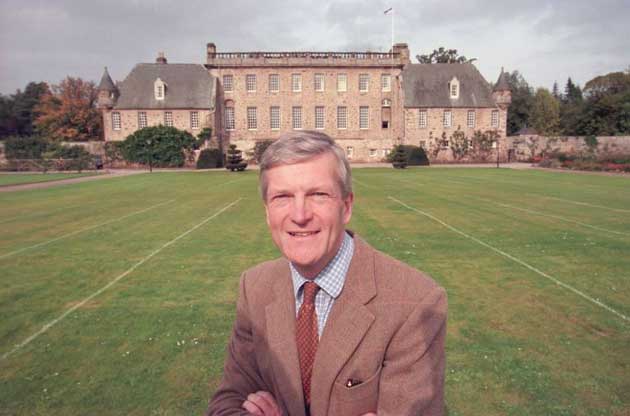

Beautifully situated on a 150-acre estate in north Scotland, Gordonstoun School has educated three generations of British royalty. Eight in 10 pupils are boarders and more than a third come from overseas.

Two hundred miles further south, Lomond School near Glasgow draws most of its students from a wide local area. Around one in 10 are boarders and more than half of them are children with parents serving abroad in the armed forces.

Gordonstoun charges some of the highest fees in the country: up to £19,569 a year for day pupils and up to £26,211 for boarders. Lomond’s fees are up to £,8,085 for day pupils and up to £17,295 for boarders. So when the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator examined both schools to decide if they provided sufficient public benefit to retain their charitable status, which one got through?

Not Lomond, which takes mainly Scottish children, but Gordonstoun, the school with one of the most distinguished lists of alumni in the country, including the Duke of Edinburgh, the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, the Earl of Wessex, Peter and Zara Phillips, the sons of Sir Sean Connery and David Bowie, plus the grandchildren of Charlie Chaplin and John Paul Getty.

Its principal Mark Pyper claims that Gordonstoun has always been socially broad. “You can’t say it is a posh and exclusive school just on the basis that a few members of the royal family came here,” he says. “We have always done well at getting money from outside, from charities and trusts and from our own funds to put into bursaries because we want a social mix and this was recognised by the regulator.”

The reform of charity law in Scotland is a year ahead of that in England, but in both countries, independent schools are no longer deemed charities just because they are involved in education. Instead, they must show they provide sufficient public benefit to justify their charitable status and the tax breaks that go with it. New rules have been published that they must obey.

But the question that the Charity Commission in England has yet to answer with any precision is what it means by public benefit. Within the next few weeks, things may become clearer when it announces a decision on five “guinea- pig” schools that volunteered to be scrutinised to help clarify the new rules. The schools – Pangbourne College in Berkshire, Manchester Grammar School, Manor House School Trust in Dorset, Hampshire and Wiltshire, St Anselm’s in Derbyshire and Highfield Priory in Lancashire – have opened their books to the Charity Commission.

The Charity Commission has thereby seen the amount of fee remission through means-tested bursaries that the schools give and the work the schools do with others in the state sector or within the community.

Associations for schools in England are struggling to advise governing bodies how to satisfy the criteria and have been looking carefully at the Scottish decisions, which they believe could indicate thinking south of the border.

The Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005 is more explicit about the public-benefit test than the Charities Act 2006 in England, but Judith Sischy, the director of the Scottish Council of Independent Schools, says subsequent guidance from the Charity Commission in England suggests the principles are much the same.

Of the 11 test-case schools scrutinised by the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, four failed the new test and were given three years to comply last October and seven had their charitable status confirmed.

According to Sischy, the regulator treated the schools individually and looked at their specific circumstances. “The basic message is that the higher the fees, the more the regulator will see what is done to mitigate the fees for families of low and modest incomes,” she says. Within the organisations representing fee-charging schools in England, there is concern over the Scottish regulator’s decision to use a fairly rigid formula to assess public benefit, the proportion of total annual income that is spent on means-tested bursaries to reduce the fees for lower-income families.

If the Charity Commission follows the lead of its Scottish counterpart, wealthy schools such as Eton, Millfield and Westminster that benefit from long-standing endowments, bequests and charitable donations, are most likely to pass the public-benefit test despite their higher fees, because of their bursary schemes. Of the five test cases, Manchester Grammar is the one most |likely to meet the criteria because of its means-tested bursaries that help 14 per cent of pupils.

If England follows Scotland, middle-income parents will lose the non-means-tested scholarships for talented pupils as more are switched to bursaries, and less wealthy schools that can’t raise sufficient money through fund-raising will have to put off building plans, increase class sizes or charge higher fees.

In Scotland, there is relief among heads that the public-benefit test has come down to a straightforward calculation of bursary help. At the same time, there is concern that the regulator’s liking for free places could produce an intake more polarised between rich and poor, with middle-income parents squeezed out.

At Gordonstoun, for example, the high fees did not jeopardise its charitable status, because at least 80 pupils – 13.4 per cent of the roll – received means-tested support. Sixteen pupils had free places and nearly 4 per cent were getting discounts worth more than 80 per cent. More than £1m was being spent on means-tested support, representing 8.8 per cent of the charity’s income, according to the regulator.

By contrast, Lomond School used only 1 per cent of annual income on means-tested support, because the children helped by the armed forces were counted as paying full fees. The school’s reduction in fees for forces children was discounted, as it was not means tested.

Surprisingly, little account was taken of the extent to which schools shared their expertise and facilities with others in the state sector or with local communities. In England, the government has encouraged independent schools to enter into partnerships with state schools, and the Independent Schools Council is advising schools to check the wording of their governing documents and to update them where necessary. A foundation document would usually put the trustees under a duty to make its pupils a primary focus for resources, premises and teaching, whereas the new charity test seeks evidence of benefit to the wider public, it says.

Martin Stephen, the High Master of St Paul’s, says his school was founded to educate able children in Greater London. It does that with its own pupils and through links with other schools and clubs that use its facilities and attend lessons.

“We think the Charity Commission will take account of that and take a wider view than the Scottish regulator, who placed a narrow emphasis on means-tested bursaries,” he says. “If it doesn’t, it will run the risk of invalidating the whole process in the eyes of the local community.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks