Generating Genius began tutoring gifted Afro-Caribbean boys in science - now the charity is mentoring boys and girls of all races

In 2005, 10 gifted Afro-Caribbean boys were tutored in science to try to reverse the trend for under-achievement in their ethnic group. Now, Generating Genius mentors 900 boys and girls

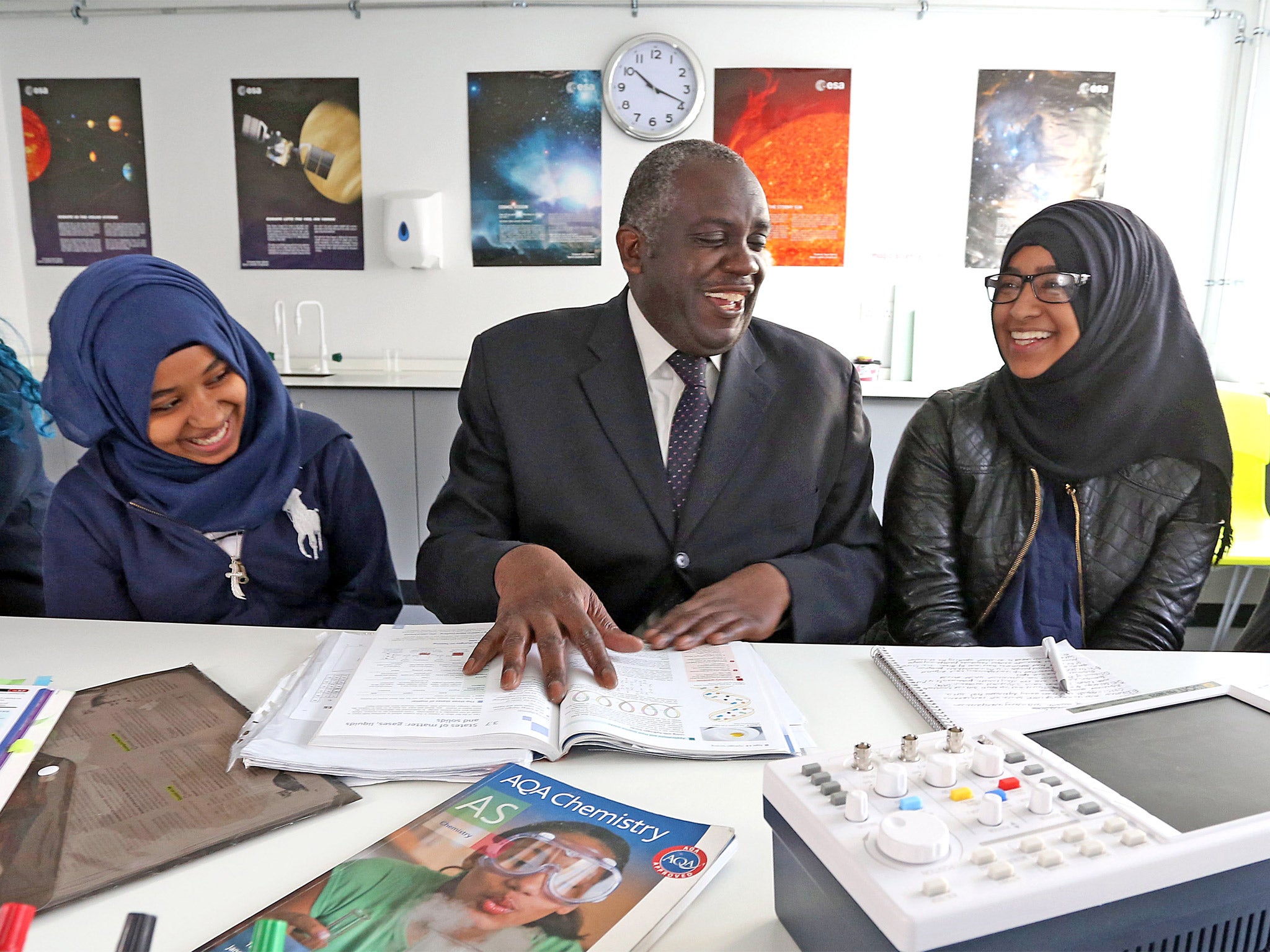

It started off as a project to help what was then the UK's most under-performing group of pupils – Afro-Caribbean boys – to succeed in science, an area that they might never have thought of studying. Generating Genius, a charity founded by respected academic Dr Tony Sewell, selected 10 boys and set about teaching them, with the aim of helping them to win places at top Russell Group universities.

There was great competition for the places on the scheme, which was advertised in the black community newspaper, The Voice. In all, 200 young people applied for the 10 places. The number on the project soon expanded to 40.

"We looked at the figures for Afro-Caribbean boys at that time [2005]," Dr Sewell says. "Under every indices in terms of exclusion, they were the under-performers. I wanted to show to them, their parents and the world that under-achievement was something that we could easily do something about."

The 12- to 13-year-olds on the programme were selected because they were top performers in their national curriculum tests at 11 – the kind of pupils who should have gone on to get A* or A grades at GCSE, but frequently did not.

For the first 10 pupils, the course began with a four-week trip to Jamaica. "Jamaica is not associated with science, but it has a good university in the University of the West Indies," Dr Sewell says. "We wanted them to be in an environment where they could see scientists, policemen, prime ministers and university vice-chancellors who looked like them and had obviously succeeded."

The project caught the attention of the media both in the UK and in Jamaica – as a result of which the boys were interviewed as they touched down to start their four-week stay.

"They became celebrities," says Dr Sewell. "They had people pointing at them in the street and saying: 'They're the geniuses!' We were trying to create a cohort of bright kids for whom it felt safe to actually be bright. On their estates, it was not actually cool to be bright. We have these terms, 'geek' and so on, to describe people who do well in science."

The project did not stop when they returned to the UK. The boys were assigned mentors to help them with their studies. This is where Dr Sewell believes his project differs from others, which may offer pupils a glimpse of what it might be like to succeed, but then do not stay with them during the five years of compulsory schooling to help them through to GCSEs.

It certainly seems to have paid off. Of those first 40 boys, 38 succeeded in getting a place at a Russell Group university (which represents 24 of the country's most competitive universities, including Oxford and Cambridge) to study a science.

"In addition, we had two who went to the London School of Economics to study economics," Dr Sewell says. It was a 100 per cent success rate.

Not surprisingly, demand for the project increased and Generating Genius expanded its horizons to take in girls as well. The president of the National Union of Teachers, Max Hyde, herself a science teacher, indicated in an interview in The Independent last month that she intended to spend part of her presidential year campaigning against gender stereotyping and for more girls to pursue careers in the sciences.

In addition, research began to show that it was white working-class boys who were now the most poorly performing ethnic group in the UK, rather than the Afro-Caribbean boys.

And science was still considered a no-go area for many when it came to deciding on their career options. "There is still a general problem with science," says Dr Sewell. "Scientists are still regarded as not quite of our kind and as geeky figures in society. Look at all the James Bond films – the villain is always a scientist!"

The project has mushroomed and now caters for 900 students from all over London, from all ethnic groups. It has numerous sponsors, including Barclays, Google, Johnson Mathey, Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, Shell and the RAF, as well as individual donors.

And it is also expanding to start a new project in the Medway towns in Kent in September – an area with pockets of deprivation in a county that is often characterised as leafy and privileged. "These will be mostly white, working-class boys who we will be supporting on this project," says Dr Sewell. "It is to do with creating aspiration."

Overall, though, girls now outnumber boys on Generating Genius. There are no longer visits to Jamaica for all the students, but new technology has taken over to provide those on the project with links to schools overseas and to set up competitions between groups of pupils in both the UK and Jamaica.

Dr Sewell now has a second string to his bow, with the establishment of a new free school – STEM 6 – dedicated to teaching the so-called STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths). It was launched last September in a converted office block in Islington, north London, and plans to take in 450 16- to 19-year-olds when it is fully up and running.

Some of those who have taken places at this unique sixth-form college have been with the Generating Genius project during their secondary schooling. "It was quite clear that there was a big demand from students who wanted to go on and study in a college where they could specialise," says Dr Sewell.

Students are offered a range of science subjects to study – biology, physics, chemistry, computer science, engineering – and maths. Astronomy is a new addition to the A-levels on offer. English is offered, too, but mainly for students who need to resit their GCSEs because they failed to get a C-grade pass at their secondary schools.

"We're oversubscribed already [for the second year this September]," he says. "It shows you that there is a demand for STEM subjects. It is coming from – particularly – parents' groups. I have a lot of parents here from migrant backgrounds and they've got very high aspirations for their kids. The students come here because this is a building that just does science."

The college also adopts a radically different approach to careers education. It is, says Dr Sewell, a "career-first academy" – with the whole of the ground floor dedicated to helping students plot their future career paths.

When lessons end at 3.30pm, pupils wend their way into the careers section of the college, where they can discuss their future plans with mentors and iron out any difficulties that they are facing with their courses. It is, says Dr Sewell, a very different approach to that of mainstream colleges, where career guidance is often offered only as an afterthought to students coming to the end of their courses.

The success of the Islington free school – which has overcome teething problems that included a strike threat by staff – has prompted an application to open a second STEM sixth-form college in Croydon.

From a modest beginning with 10 "celebs" visiting Jamaica for science lessons, Generating Genius has become a key player in ensuring science is no longer a taboo subject among the UK's disadvantaged young people.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks