University of Essex: Raising expectations on the east coast

Ministers want 20 new campuses to be built over the next six years. A new university building at Southend aims to lead the way – and boost the local economy too. Lucy Hodges takes a sneak preview

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Once upon a time, Southend was a magnet for day trippers from the East End of London, luring them in with the biggest fairground in the south of England. But since the 1960s it has become just another shabby seaside resort, attracting first teddy boys and mods and then new romantics and ravers to its famous beaches.

Now parts of the town centre are so deprived that they attract European Union funding. The result is that suddenly money has started to flow in to the Essex seaside resort: new shops have sprouted on the high street; the station has been refurbished; an enormous further education college has gone up on what used to be a car park; and, wonder of wonders, a university campus opened last week to add some gravitas to the facelift.

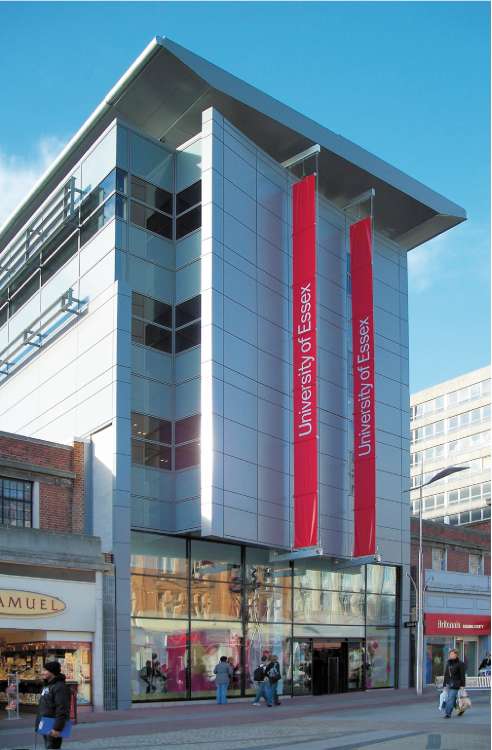

The Southend campus of the University of Essex is a large £26.2m building flashing plate glass in all directions, with amazing views of the Thames Estuary on one side and a derelict Prudential block on the other. Its aim is to revive the town's flagging economy.

"It will help to restore the physical fabric of the town centre," says Professor Colin Riordan, Essex's vice-chancellor. "But, more important, it will be a magnet, attracting outsiders to the place and making it more vibrant."

The development is part of a larger phenomenon taking place around the country as policy-makers learn the lessons of the USA and become increasingly aware of how important higher education is. As John Denham, the Secretary of innovation, universities and skills, said in a pamphlet published last week, "Higher education is estimated to be worth over £50bn to the economy each year. But the importance of accessible higher education to towns, cities and regions is no less important.

"A local, high quality campus can open up the chance of higher education to young people and adults who might otherwise never think of getting a degree. Higher education now provides the skills and knowledge transfer that enables local businesses to grow and attract new investment to the area."

This is why ministers are planning for 20 more campuses to be created over the next six years in places like Southend where there are few people going to university, to add to the 11 towns or regions that have spawned new higher education institutions in the past five years. In Southend, the University of Essex is hoping to increase student numbers to 2,000, from its current 300, by 2013.

Not everyone is happy about this £150m expansion, which could mean another campus in nearby Thurrock as well as in places such as Peterborough and Blackpool. Many people bemoan the fact that, with increasing student numbers, it has become more difficult for graduates to get jobs. They point to the 22 per cent drop-out rate as evidence that the expansion has, at the very least, been a waste of taxpayers' money or, at worst, pointless.

And there is considerable scepticism about Denham's announcement. For a start, the money is not new. It was already in the comprehensive spending review under the heading of new capital projects. So, critics view the plan for 20 more campuses as nothing more than spin.

Moreover, Pam Tatlow, chief executive of Million+, the organisation representing new universities, says that it is important to ensure that any new campus is viable. Unless there is an assured supply of students, it will fail, she says.

"At the end of the day you have to ensure that these places are going to be sustainable," she says. "You have to make sure you have enough students who are encouraged to come and can be supported through their courses."

Although David Willetts, the Conservatives' higher education spokesman, is in favour of expansion, he wonders too about the practicalities of this announcement. A sum of £150m for 20 campuses does not sound like very much when you consider that it costs £30m to build a new academy school.

There is also the question, says Willetts, whether this is the most sensible way to expand, given the success of the Open University in teaching students via distance and online learning.

The signs are, however, that ministers have enough support on their side to press on. The examples of places such as Southend and Medway where the universities of Greenwich, Kent and Canterbury Christ Church have come together, provide them with the evidence they need for their new "university challenge", as they are calling it.

At Southend, the new campus houses three completely different areas of study: the East 15 Acting School; entrepreneurship and business; and health and social sciences. They are an unlikely combination and the acting school seems out of place in the new corporate building with its shiny clean surfaces, pastel colours and no bar.

But on the day of my visit a group of 25 students on the new degree in physical theatre were learning to be clowns on the fifth floor and clearly enjoying the space and light. "It's much cleaner than we are used to but it's given us the facilities we don't have at our other site in Loughton," says Professor Leon Rubin, head of the acting school. "In any case, we are also taking over an old church in town, so that will give us the character – and a much-needed theatre."

The big question is how the acting school will revitalise Southend. Rubin is in no doubt that it will – and that it is doing so already by having street festivals all over town. When the theatre is up and running, it will also offer a new performance space. "We plan to put on high quality work," he says. "That way, we will be raising people's sights and not dumbing down."

There is no doubt that the students will be forthcoming because the school has been receiving 1,400 applicants a year for its 50 to 60 places. There is plenty of room for it to grow and the sparky students it admits should be good for perking up the town.

Local businessmen are being enticed into the school of entrepreneurship and business – the only one of its kind in the country – by the modular nature of the courses. To undertake a Masters you simply have to sign up for one £600 module rather than the whole of a one-year programme costing £9,000. "It means you can stack up your modules and spread them over a five-year period to gain an Msc," says Patrick Gallagher, administrator in the department. "Or you can take a year out while clocking up your modules."

The school attracts more overseas than domestic postgraduates (the undergraduate degree is only in its first year) and next year will be looking to start an MBA. The department is growing fast. When it started two years ago, there were six students applying for the business entrepreneurship Masters: now there are 106. And on the international marketing Msc there are now 135 applications.

This educational effort is complemented by a business hub that has 20 incubator units, helping local start-up companies to get the help they need. After less than a year it is almost full. The health and human sciences department is similarly vocational. Southend offers oral health training via a foundation degree to 15 budding dental hygienists a year, who practise on plastic heads in a lab kitted out with the latest equipment, including plastic teeth which they learn to clean.

This course is seriously oversubscribed, according to Professor Kimmy Eldridge. Staff have to give applicants an extra test to weed out those who would make the best cleaners of teeth.

The department also trains nurses, pharmacists and other health professionals how to prescribe drugs and offers another foundation degree course in health science and postgraduate training to professionals involved in training.

All of which shows what the creation of a new campus on a former Odeon cinema site can do to rejuvenate a neglected Essex seaside town. It also illustrates that a university can be global, national and local, all at the same time, according to David Eastwood, chief executive of the Higher Education Funding Council, who attended last week's opening.

"It can have world-class research strengths, it can recruit nationally and internationally, and it can also be accessible and directly beneficial to the places in which it is located and the people who live in them."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments